SEOUL, South Korea (CNS) — One of South Korea’s most senior clergymen says he believes the Catholic Church in communist North Korea is growing, although Catholics live in hiding and endure persecution.

Archbishop Victorinus Youn Kong-hi, 97, former head of the Archdiocese of Gwangju, South Korea, made the remarks in a recently published book on the history of the North Korean church, reported ucanews.com.

“The Story of the North Korean Church” is a Korean-language, comprehensive book on the history of the Catholic Church in the northern part of the Korean Peninsula based on eight interviews with the archbishop last year.

[hotblock]

Writer Kwon Eun-jung penned the book sponsored by the Catholic Oral History Records for Peace on the Korean Peninsula project of the Catholic Institute for Peace in Northeast Asia, a body under the Catholic Diocese of Uijeongbu, Korean news portal chosun.com reported May 13.

In the book, the elderly churchman, who was born in an area now covered by North Korea, gave vivid testimonies of how the church thrived in the territory before the Korean Peninsula was divided between the democratic South and communist North and the eruption of the Korean War.

The missionaries distributed medicines to poor people who needed medical attention, established schools and carried out other charitable works to support local Catholics, who were poor but very enthusiastic, he said.

The archbishop recalled how Catholic clergy, religious and laypeople were gripped by fear as the communist forces attacked churches as the war broke out in 1949.

At midnight May 9, 1949, an unexpected, emergency bell rang at the Tokwon Benedictine monastery and seminary near Wonsan. The German-born chief abbot, Bishop Boniface Sauer, was dragged away by the communists, recalled the archbishop, who was a student in the seminary at the time.

These were the last words of the abbot to the students before he was taken away: “As the Lord has called, and as the Lord has done, we must go out to the death with countless martyrs. Now, I am asking you to take this place without me. Go back and rest in peace. Let’s meet in heaven.”

The abbot was later martyred in a North Korean prison. Ucanews.com said because of his long, white beard, fellow monks identified him among scores of bodies and buried him in a cemetery.

[tower]

Four days after the raid, the communists expelled 26 monks of the monastery and 73 seminarians. They departed without any sacred objects, including robes, rosaries and even a book. The monastery and the seminary closed due to war and persecution of Christians.

Unconfirmed media reports suggest the structures still exist today.

The end of World War II in 1945 saw Japan leave Korea following decades of colonization. On the day of liberation, the people wanted to ring bells to express their joy, but many failed to do so.

“I don’t remember hearing the bell to announce the joy of liberation that day. This is because, at the end of the war, the Japanese imperialists took away all the metal,” recalled Archbishop Youn, who was then a philosophy student in the seminary.

However, the joy of liberation was short-lived as the communists took over North Korea and confiscated all church properties before unleashing a reign of systematic persecution.

Archbishop Youn said he and Bishop Daniel Tji Hak Soun escaped from the North to the South and reached Seoul Jan. 17, 1950, where they bought chocolate and milk.

“We felt the air of freedom,” he recalled.

After moving to the South, Archbishop Youn said, he visited North Korea to visit his entire family. Like him, Bishop Tji Hak also visited his brother and sister during a reunion in the North Korean capital in Pyongyang in 1985.

Archbishop Youn was born in 1924 in a Catholic family in Jinnampo of Hwanghae, now part of North Korea. He was ordained a priest March 20, 1950.

In January 1951, he was appointed the chaplain of the U.N. concentration camp for war refugees in Busan.

Father Youn studied theology in Rome at the Pontifical Urbanian University and Pontifical Gregorian University from 1957 to 1960.

In 1963, he became the first bishop of the Suwon Diocese. He was appointed archbishop of Gwangju in 1973 and served until 2000. He also served as the chairman of Gwangju Catholic University from 1973 to 2010.

He served as the president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Korea from 1975 to 1981.

The nonagenarian archbishop said the publication of the book has made his dream come true. He said he can do nothing for the North Korean church other than praying for peace.

He said he believes the “church is growing in hiding, just like the trees of Tokwon seminary.”

“The trees sprout new shoots in each branch each year. Like that, the Catholics who are hiding somewhere in the North are also growing,” he said.

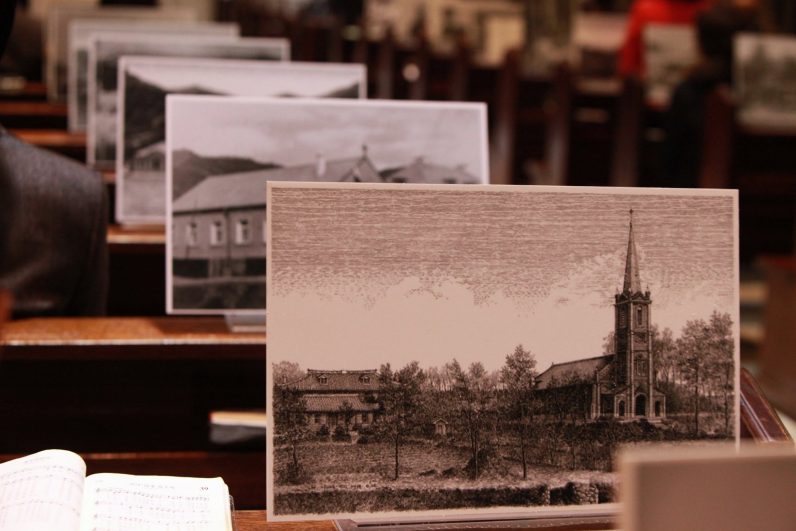

Some vintage photos of North Korean parishes are seen Nov. 24, 2015, inside the Myongdong Cathedral in Seoul, as a remembrance of the Catholic Church in North Korea. (CNS photo/courtesy Archdiocese of Seoul)

PREVIOUS: Chaos, curfew after arrests in mob murder of student accused of blasphemy

NEXT: World in ‘profound anthropological crisis,’ pope says

Share this story