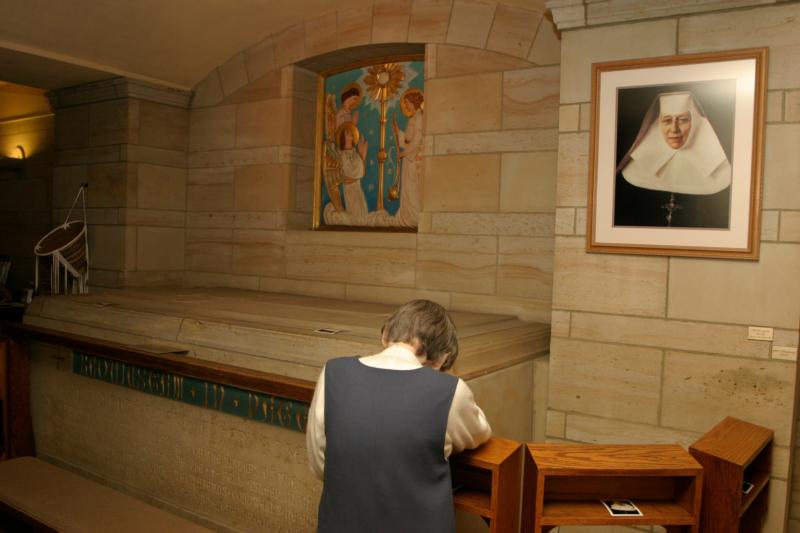

A Sister of the Blessed Sacrament prays before the tomb of the congregation’s foundress, St. Katharine Drexel, in May 2016 at the motherhouse in Bensalem. Her feast day of March 3 stands like a beacon at the beginning of Lent. (Sarah Webb)

The three pillars of Lent — prayer, fasting, almsgiving — enrich our spiritual life during this penitential season. But they can also be challenging.

Saints can shed light on our journey. So let’s begin with almsgiving and look to St. Katharine Drexel as a profound example of the depth to which this practice calls us.

In many ways, Drexel is a saint for our time. She died in 1955 at the age of 96, and her feast day of March 3 stands like a beacon at the beginning of Lent.

[hotblock]

Born in Philadelphia into great wealth, Drexel was a debutante, a world traveler, a well-educated girl who made the society pages. Using the jargon of the Gilded Age, when extravagant displays of wealth marked success, she had every opportunity to marry “well.”

But Drexel heard a different call. Like a page out of today’s news, the plight of people of color in the U.S. troubled her. On a European tour, she met Pope Leo XIII and encouraged him to send more missionaries to serve Native Americans. The pontiff replied by asking her why she didn’t become a missionary.

Eventually, Katharine forsook her status to found an order of missionary nuns and dedicate her life and fortune to serving Native and African-Americans. Reportedly, this prompted a late 19th-century headline that could have been ripped from today’s tabloids: “Gives up Seven Million.”

Among Drexel’s achievements: the founding of Xavier University in New Orleans, the first Catholic university in the U.S. for African-Americans; 145 missions for Native Americans; and a system of black Catholic schools. Drexel battled segregation until a heart attack forced her retirement in the 1930s.

Drexel’s sanctity had its roots at home: Her father and stepmother were pious and generous, reminding us that the example we give our children makes a difference. Another lesson: Unlike Drexel or the rich young man of the Gospel, we may not be called to give up everything, but our faith challenges us all to give sacrificially and to reject the false idols of status and wealth.

[hotblock2]

All saints are examples of intense prayer, but St. Ignatius of Loyola is an outstanding guide to deeper prayer during Lent. Despite being born in the Basque country in 1491, he has great relevance today. The Spiritual Exercises that he developed are considered one of the most influential books on spirituality ever written, and they have experienced a huge burst of popularity since the Second Vatican Council.

Numerous books are available to guide ordinary people in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, and a quick online search of “Ignatian spirituality” can lead to a wealth of help for Lent.

Like Drexel, Ignatius was born into wealth. A product of his era, he was infatuated with romantic ideals of chivalry and warfare that he believed proved one’s manhood and won women’s hearts.

But after his leg was seriously injured during combat, the young nobleman was forced to spend weeks in bed recuperating, where he hoped to read the romantic literature of the era. Instead, the lives of the saints were available.

Ignatius began to discern the difference he felt in his interior life after reading of saints versus reading of romantic heroes. It was the beginning of his journey into understanding God’s way of speaking to us in our own lives, a journey he eventually shared with his followers, who became the Jesuits. Today, he shares that journey of discernment with all who explore the treasure of his Spiritual Exercises.

During Lent, Catholics are asked to go beyond the fasting proscribed on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday and “fast” in some way meaningful to our unique faith journey. In a culture besotted with self-care and self-indulgence, we often question whether ascetic practices like fasting are really helpful.

[hotblock3]

Venerable Matt Talbot provides an example of someone who used asceticism to help him on his journey from addiction to wholeness. Born into a large family, Talbot lived in poverty-stricken, post-famine Ireland. He began work at age 12, and that’s when a soul-consuming alcoholism took root.

At the age of 28, Talbot, with the help of a confessor (and the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius!) began his journey of sobriety. His abstinence was accompanied by a radical conversion. A laborer and a union man, he joined the Secular Franciscan Order, gave up another addiction — smoking — and began to lead his ordinary life with extraordinary penance and self-sacrifice.

Talbot is at the second rung of a four-step ladder to canonization. A miracle attributed to his intercession could lead to him being declared “Blessed.” But in the meantime, thousands believe he has helped them in their struggle with addiction.

All of us are attached to something that impedes spiritual growth. During Lent, fasting from a behavior — drinking, gossiping, addictive screen time — that interferes with our relationship with Jesus can lead to conversion. An attribute of Talbot was that people described him, despite his self-denial, as a very happy man.

May the discipline of fasting, the discernment of prayer and the justice of almsgiving bring us joy this Lent.

***

Caldarola is a freelance writer and a columnist for Catholic News Service.

Share this story