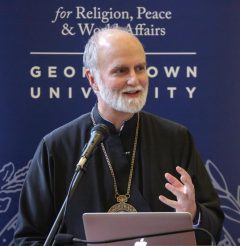

Metropolitan-Archbishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia speaks at Georgetown University in Washington Oct. 25, 2019. The archbishop spoke about the church’s role of support during Ukraine’s Soviet occupation and its ministry now of helping people find healing and keeping the faith alive while numbers are dwindling. (CNS photo/Georgetown University)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Addressing an audience at Georgetown University Oct. 25, the leader of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the United States said the world news in Washington is as “Ukrainian as it ever has been.”

But although he made reference to the current political interest in Ukraine, he also said “no one in Washington would give (the country) the time of day had there not been a July phone conversation,” referring to President Donald Trump’s conversation, now under congressional investigation, with Volodymyr Zelenskiy, Ukraine’s president.

The church leader, Metropolitan-Archbishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia, was not at the college campus to talk politics, but to address the role of Catholic social teaching in Ukraine during Soviet occupation and the church’s continued role both in the country and for the Ukrainian diaspora throughout the world.

“The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has tried to present Catholic social doctrine in a lived way,” he said, in a presentation sponsored by Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs and the university’s Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life.

“How this will prevail, we have yet to see; we all have great hope,” he added.

The archbishop, who became leader of the U.S. Ukrainian Catholic Church in June after leading a Paris-based eparchy for nine years, also is founder and president of the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. His public lecture wrapped up a weeklong visit of a delegation from the Ukrainian university to Georgetown.

[hotblock]

The archbishop said it was tricky to address the group because there were plenty in the audience at the Jesuit residence on campus who could teach him about social doctrine and Ukrainian history.

He spoke of the challenges faced by Ukrainian Catholics during Soviet occupation when church leaders were sent to forced-labor camps in Siberia. He said ethic cleansings before, during and after World War II made the country one of the most dangerous places in the world. “If you lived there, you were most likely to be killed,” he added.

For older Ukrainian Catholics to move beyond the hardships they went through is very difficult, because “fear becomes part of your DNA,” he said.

Archbishop Gudziak was born in Syracuse, New York, the son of immigrant parents from Ukraine. He said he frequently visits his aunt, who is in her 70s, and every time he sees her “she speaks about the trauma of the war.”

He said she, like many others, are in the predicament of “bearing the scar of communist totalitarianism.”

As a way to respond to sufferings, not only for older Catholics but for younger members struggling with any number of issues, he said there was going to be a healing service at the Ukrainian cathedral in Philadelphia in early December where bishops would anoint anyone who wants special healing.

[tower]

“I believe the Lord works,” he said, adding that those in the church can help one another “move out of clutches and spasms — if only for a moment — to realize and feel the graces of God.”

After World War II, he said, the Ukrainian Catholic Church provided spiritual support and aided tens of thousands in resettling, establishing schools, orphanages and junior colleges in other countries.

Now, it’s a different story. The church is no longer the leading group of support, especially as “secularism undermines religion,” he said, noting that this current movement away from the church is something he is just beginning to learn and understand.

“I’m all ears for suggestions,” he said.

When the Ukrainian Catholic Church was legal again in 1989, its leaders issued pastoral letters and multiple documents on social justice, always emphasizing human dignity.

Now he said there is a “need to go back to basics.”

He said the church’s influence peaked with its emphasis on dignity in the ’90s, but now the church there, as in most countries, he said, is “not finding effective language to speak with young people” and is seeing vocations and numbers in general declining.

He has seen the same trend with the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the U.S. where its Philadelphia cathedral that can seat 1,200 but has about 140 people at Sunday Mass.

[hotblock2]

The archbishop is not by any means throwing in the towel; instead he said the church is being “stripped down to essentials.”

He said when he was leader of Ukrainian Catholics in Paris, he wondered if the church could keep up against all the outside pressure and asked: “What is this all about? Is this a little ethnic museum that will peter out, or is this the church of Christ?”

His answer, then and now, of course, is the latter.

And for now, he told his audience: “Just do your lousy best. Laugh, hold each other by the hand. Never will the gates of hell prevail against the church.”

And for added measure, he said: “Let’s be confident and move forward.”

PREVIOUS: Religious from Latin America train to serve in U.S. mission dioceses

NEXT: Everyday Heroes: Father, daughter make cross-country pilgrimage for life

Share this story