WASHINGTON (CNS) — When a few hundred people met in Washington recently to discuss ways to solve the nation's high poverty rate, one group was noticeably missing from the discussion: those actually living in poverty.

That did not go unnoticed by participants and speakers who mentioned their absence and said they hope to add the voices of the poor to future gatherings.

They also said they want to include them more in day-to-day efforts to reduce poverty.

[hotblock]

Advocates for the poor came together Sept. 21-22 for the National Poverty Summit, co-sponsored by Catholic Charities USA and the Corporation for Enterprise Development, which empowers low- and moderate-income households to build and preserve assets.

In a breakout session Sept. 22, Sheila Gilbert, national president of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, urged members of volunteer agencies to make sure “every person you interact with becomes a volunteer for you.”

Gilbert said those in poverty should not simply be given help but must be considered “one of us.”

And that's not the only change she thinks should happen in how social agencies operate. She thinks such groups need to focus on how to better share resources with other organizations doing similar work.

“Helping people survive, we're good at that,” she said, noting that social service agencies need to do more long-term thinking, planning and collaborating.

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul, based in St. Louis, is a Catholic lay organization committed to helping the poor around the world. Gilbert acknowledged that the organization, like many other social service groups, can become accustomed to “patching lives together” and essentially “living in tyranny of moment” by helping those in poverty get through each crisis as it comes up.

She said the way many organizations operate is very similar to how those in the cycle of poverty function: focusing on one crisis at a time. As she put it, one week they try to come up with cash to pay the electric bill and then another week they avoid being evicted “without getting a chance to step back or make a plan.”

Gilbert said social service agencies experience that same frustration especially as they work with fewer resources and end up taking on more caseloads.

What she hopes will happen is a renewed sense that “we are all in poverty together and there has to be a better way for us to work together to make a difference.”

Delivering a keynote address at the summit was Peter Edelman, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center and author of the new book “So Rich, So Poor: Why It's So Hard to End Poverty in America.” He, too, acknowledged the major workload faced by those trying to eradicate poverty and then asked them to do even more.

Edelman told participants he knew they were “stretched” but said they needed to also be active in advocating for public policy change: electing those who understand issues facing the poor and then to “keep on lighting fire under these leaders.”

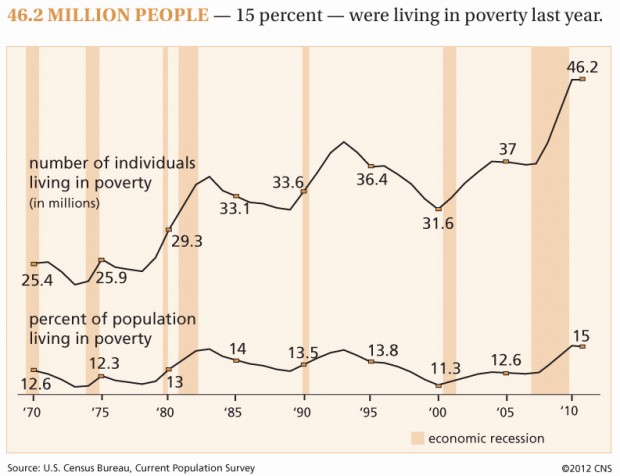

Currently, there are more than 46 million people living in poverty in the United States, he said, and that number would double if there were no government programs in place to help them.

“We're sort of out of tricks to help these people,” he said, stressing that government leaders need to take action.

“Get civic leaders to see what's happening,” he stressed, urging those in social service agencies to invite people to see the work they do.

At the summit, those who work every day with those in need experienced a dose of what these people experience through a poverty simulation.

During the exercise, participants were assigned to take on the role of a person — such as a single mother, an unemployed man, a senior citizen — and were given a packet of information about that person's assets and responsibilities. For the next two hours — simulating four 15-minute weeks — the participants tried to meet their responsibilities while making ends meet.

Greg Kepferle, CEO of Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County, Calif., who coordinated the program at the summit, said his agency has been running the simulation program for the past four years with the group Step Up Silicon Valley, a collaborative effort by Catholic Charities and local nonprofit service providers, faith-based organizations and government representatives.

He told Catholic News Service the simulation program — which makes people understand the amount of frustrations and challenges people in poverty experience on a daily basis — has been offered to high school students, CEOs, politicians and stay-at-home moms.

“The first step to eliminate poverty is to be aware of it,” he said.

Summit participants certainly were already aware of the poor's struggles, but Kepferle said the simulation experience reiterated what one of the event's speakers, columnist E.J. Dionne, said: “It's not that the poor have too little responsibilities; they are drowning in responsibility.”

PREVIOUS: Cardinal encourages Catholics to help transform world with their faith

NEXT: St. Louis to host day of prayer to implore Mary’s blessing upon nation

Share this story