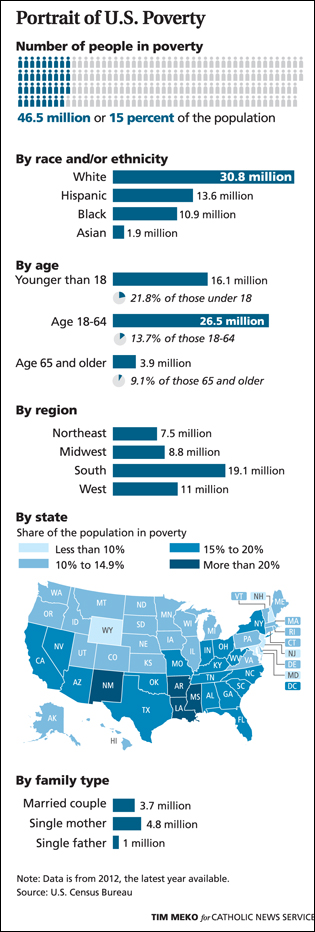

FORT MEADE, Md. (CNS) — According to Census Bureau estimates released Sept. 17, there are 46.5 million poor people in the United States.

This is the story of one of them.

Samantha — she asked that her last name not be used — and her family are currently staying at Sarah’s House, an emergency and transitional shelter run by Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

[hotblock]

The story of Samantha, 30, and her family is not one of abject desperation. But it is a story of how one small setback after another piles up and has a snowball effect.

Samantha grew up in a Maryland suburb that borders Washington. Her husband grew up in another border suburb just east of her own.

Her husband has woodworking and cabinetry skills. Samantha stayed at home, raising the couple’s four children while her husband worked.

Then came the recession of 2008. The woodworking business slowed; orders for cabinetry dropped off. Samantha’s brother-in-law invited them to live with him in a city about midway between Washington and Baltimore.

While they lived there, Samantha had two more children, now ages 2 and 3. But the distance from her husband’s network of connections and clients, coupled with unreliable transportation, made getting jobs tougher. In the meantime, the brother-in-law started demanding that his down-on-their-heels relatives pay rent and utilities.

“This was really the worst decision we made,” Samantha told Catholic News Service in Fort Meade, where Sarah’s House uses decommissioned barracks at the Army base for its shelter services.

Once Samantha and her family left the brother-in-law, they started living in motels, until the cheap motels with long-term rates ran out — and their money ran out. “It was a stressful time,” she acknowledged.

It wasn’t long after Labor Day when the family realized they had no place to go. They sought help at the Department of Social Services in Anne Arundel County, in which Fort Meade is located, and were referred to Sarah’s House.

It wasn’t long after Labor Day when the family realized they had no place to go. They sought help at the Department of Social Services in Anne Arundel County, in which Fort Meade is located, and were referred to Sarah’s House.

Samantha dreaded the shelter because she knew the stereotype: rows and rows of cots, lots of noise and chaos, and the fear of unwittingly stirring trouble with other homeless residents — of which she was now one.

She also hated the prospect of being forcibly separated from her husband. But Sarah’s House accepts adult men as well as women. And the atmosphere was far removed from the stereotype.

“It was quiet, it was really nice. It was clean,” she said.

For the first couple of nights, Samantha and her family had to sleep on cots because there was no other place at Sarah’s House for them to sleep. But residents in the emergency shelter portion of Sarah’s House made the transition to apartment-style barracks living at the complex, opening up some beds.

Already by the time CNS had interviewed Samantha, Sarah’s House had worked with her and her husband not only to get on a chore schedule in the shelter’s common areas, but also to put together a plan to ensure their financial stability within the next year and a half.

Part of the plan includes getting jobs. Samantha’s husband quickly found one at a Big Lots store close to Fort Meade. Samantha had her bid in on a job at a Dollar Tree store also relatively close to the base.

Before having her children, “I was a caregiver,” a job she liked, she said. “I’d like to go back to doing that, but I don’t have my high school diploma.” She added her next step was to get a diploma, then study college-level nursing.

Speaking of school, one of the first things Sarah’s House did was to get Samantha’s four school-age children enrolled in the neighborhood public school. Asked if her kids felt any stigma about being at a shelter, she dismissed the question, instead practically bubbling over with enthusiasm. “They’re all doing great. They really love the hot lunch” at school, she said. And when they came back from school one mid-September afternoon, Samantha asked them, “What did you have for lunch today?”

With a job, Samantha and her family would be eligible for transitional housing, where the family can build up its income and savings while looking for suitable housing once they leave Sarah’s House. And it just so happened that a three-bedroom apartment had just been vacated the day before. The furnishings are hardly lavish — they resemble something that might have been part of a college dormitory lounge in the 1970s — and the beds are nothing to write home about, but the beds can be bunked, and the apartment has a washer, dryer and stove.

Despite all the indignities that can come with poverty, said Joyce Swanson, director of client services for Sarah’s House, “the one thing people say they miss most about not having a place to live is not being able to cook for your family.”

PREVIOUS: He used to be poor, but that was long ago

NEXT: Pope names Bishop Hebda of Gaylord to be Newark coadjutor archbishop

Share this story