BUTLER, Pa. (CNS) — The history of slick water hydraulic fracturing extends back more than 60 years as America seeks solutions to its seemingly unquenchable thirst for energy.

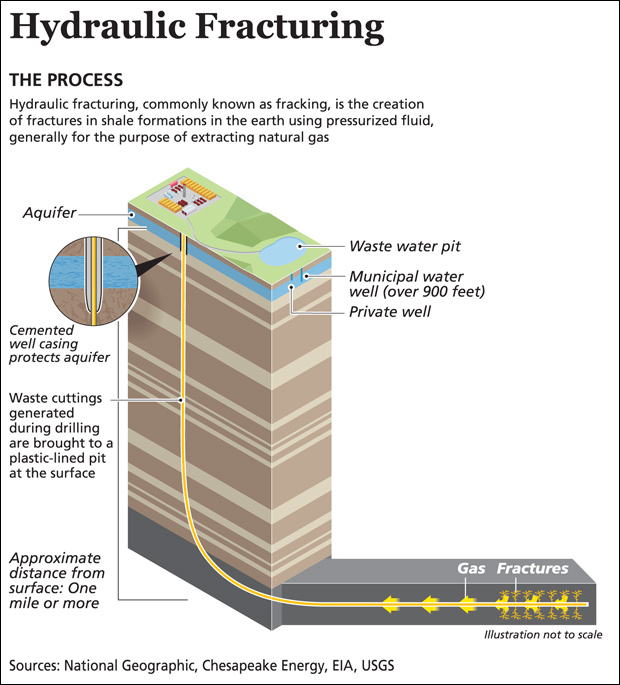

Also known as fracking, the process has been used to extract oil and natural gas since 1947, said Peter MacKenzie, vice president of operations for the Ohio Oil and Gas Association. He and other industry representatives argued that the process is safe and even when problems occur, companies work to alleviate any concerns.

(See related stories: Fracking debate examines America’s quest for energy and Catholic voices raise moral concerns over fracking)

(See related stories: Fracking debate examines America’s quest for energy and Catholic voices raise moral concerns over fracking)

Advances over the years have allowed the process to be readily duplicated across the country. These days the Marcellus Shale under Pennsylvania is among the most active natural gas plays in the country. Along with the rapid development comes questions about safety and environmental protection.

“Certainly folks have questions and they deserve answers,” Travis Windle, spokesman for the Marcellus Shale Coalition, an industry group, told Catholic News Service.

He suggested, though, that all Americans benefit from the shale development through lower priced natural gas, while the people of Pennsylvania have seen more than $1.8 billion in tax revenues and $406 million in impact fees for wear and tear on infrastructure and increased demands on local communities.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated in 2009 that the U.S. had 1,722 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas in six key shale formations, including the Marcellus in the northeastern U.S. EIA projected that identified natural gas deposits in the shale plays was enough to supply the country’s needs for 90 years at then-current production rates. Other estimates of shale gas reserves extend the supply to 116 years.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated in 2009 that the U.S. had 1,722 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas in six key shale formations, including the Marcellus in the northeastern U.S. EIA projected that identified natural gas deposits in the shale plays was enough to supply the country’s needs for 90 years at then-current production rates. Other estimates of shale gas reserves extend the supply to 116 years.

It is the tremendous gas reserves in the Marcellus Shale deep under Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and West Virginia that have attracted the interest of the country’s largest energy firms — Shell, Chevron, Range Resources, XTO Energy, Hilcorp among them.

In Pennsylvania, wells have sprouted from Greene County in the southwest to Susquehanna County in the northeast. In West Virginia and Ohio, where the Utica and Point Pleasant shales also come into play, production is in its early phases. New York’s long moratorium on drilling remains in place as a study on the health effects of fracking continues.

[hotblock]

U.S. Catholic Church leaders have largely remained neutral on shale gas development nationwide, neither supporting nor opposing it outright. However, state Catholic conferences in New York and Ohio as well as individual bishops have posed numerous questions stemming from Catholic social teaching on the environment for officials to consider and the public to mull over.

In public comments submitted to New York officials in January 2012, the New York State Catholic Conference cited several concerns that it considers crucial in deliberations on lifting the state’s moratorium on fracking.

The detailed statement pointed to the need for public input on all industry regulations; promoting citizen awareness of social and economic costs of fracking including job creation and sustainability; the potential for contamination of drinking water; transparency on chemical usage; industry responsibility for cleanup of fracking fluids; payments for withdrawal of water from public sources; adequate buffer zones between wells and homes, business, schools and hospitals; and home rule for local communities to regulate well development.

“All of these things come directly out of Catholic social teaching,” said Richard Barnes, the New York conference’s executive director. “We didn’t comment in a way that we were answering the questions so much as we were asking state officials to make sure that they were addressing the questions.”

Meanwhile in Pennsylvania, where environmentalists, hunters and farmers have organized campaigns against the energy industry, the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference has yet to address fracking, said Amy B. Hill, the conference’s executive director.

“As a whole as far as public policy is concerned, we have stayed out of that debate because it affects the dioceses in different ways,” Hill said.

Government and energy company representatives told CNS they take the concerns raised in New York and elsewhere seriously and value the environment just as much as people of faith.

“Those are values we share as well. It’s our environment as well,” said Patrick Henderson, Pennsylvania energy executive and deputy chief of staff to Gov. Tom Corbett. “We’re all members of multiple different communities, but those values shape the policies we make every day.”

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down parts of a state law Dec. 19 that had restricted the ability of local municipalities to control where natural-gas drilling could occur on the local level. The law, known as Act 13, had been promoted by the Corbett administration and the Marcellus Shale Coalition.

The court ruled the local zoning provisions of the law were unconstitutional. (Read more here.)

Windle, the coalition’s spokesman, said the development of the natural gas fields is vital to a stronger economy because of the jobs it creates as well as U.S. energy independence. The expansion of fracking has led to greater employment opportunities, fewer carbon emissions because natural gas is cleaner than coal and has lower energy costs, he said.

“If we are serious about raising people up and growing opportunity, we need energy and we need affordable energy to do so,” he told CNS.

Despite industry and government assurances, some, like Jennifer Schaffner of Summit Township, Pa., in Butler County, questioned the appropriateness of fracking, especially near schools and residences. Her focus is on the gas well within 1,000 feet of Summit Elementary School, where her son and daughter attend classes.

Schaffner, who said she belonged to a Catholic parish in Butler that she declined to identify, told CNS her children became ill soon after workers began flaring the well within days of the start of classes in September.

Flaring is a short-term process in which gases are burned off once a well starts producing after it is fracked in order to test the quality of the gas being extracted and stabilize pressure in the well to reduce the risk of an explosion.

Schaffner said her children experienced dizziness and nausea. Her daughter’s symptoms lingered for more than a week and required a visit to the family doctor, who, Schaffner said, attributed the illness to a virus.

However, Schaffner said she believes it was gases from the flaring that sickened her children.

Karen Matusic, public and government affairs manager for XTO Energy in the company’s Appalachia Division office in Warrendale, Pa., said in an email to CNS the company was unaware of any illnesses after the flaring began. She explained that XTO contacted local officials, a local community advisory board and the head of maintenance at the school after receiving one inquiry about the flaring, which occurred Sept. 3-9.

“While there is no requirement to notify the school, we have realized that more extensive outreach to the community could have alleviated some concerns,” Matusic wrote.

Schaffner was among a small group of parents and anti-fracking activists attending a prayer service at the school Sept. 25. The 20 people who attended read from Scripture and offered prayers for the protection of children.

A week after the prayer service, Schaffner told CNS that she remained concerned about the well’s presence near the school and suggested the need for continuous testing of the air and nearby groundwater sources.

“You can’t undo the well, and I get that,” she said. “But (it’s important) to keep the children and the parents’ minds at ease. If there’s nothing wrong with it, I don’t see why self-monitoring would hurt.”

PREVIOUS: Catholic voices raise moral concerns over fracking

NEXT: Fracking debate examines America’s quest for energy

This reminds me of the BP Gulf coast oil spill of several years ago. If dollars are involved, BP or the Pennsylvania fracking companies will tell the public anything it wants to hear to avoid losing their economic rewards. At the same time, there is no reason the Catholic Church has to be involved in this issue. As the former President of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops Archbishop Gregory articulated, we don’t have to be involved in every issue and produce a brochure on every topic.