NEW ORLEANS (CNS) — It was the seminal event of Western Christianity over the past 500 years.

Martin Luther, a German Catholic monk, sent his “95 Theses,” or “Disputation on the Efficacy and Power of Indulgences,” to the local archbishop Oct. 31, 1517. And he set into motion the Protestant Reformation that four years later prompted his excommunication by the Catholic Church and laid the groundwork for denominational splintering that over the centuries has led to the formation of thousands of Christian churches.

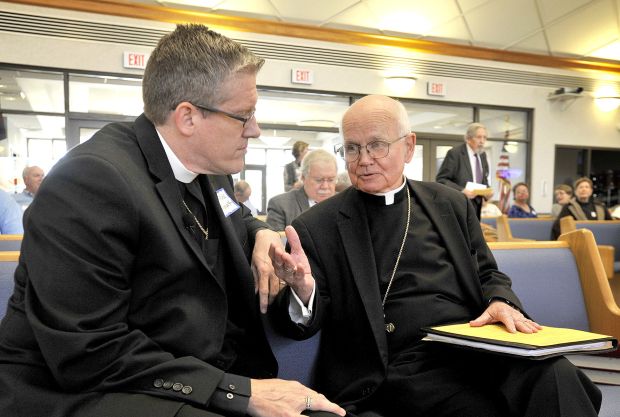

Over the past 50 years, especially with the impetus provided by the Second Vatican Council, those divisions between Catholics and Lutherans have begun to heal and the pace of concrete efforts toward restoring unity has quickened, retired Archbishop Alfred C. Hughes of New Orleans told a recent ecumenical gathering at Christ the King Lutheran Church in Kenner.

[hotblock]

“The international and national dialogues between Lutherans and Catholics in the last 50 years have yielded significant truth,” Archbishop Hughes said, prompting Catholics “to revisit the person and motivation of Martin Luther” in advance of the 500th anniversary in 2017 of the publication of Luther’s theses.

“His genuine desire to promote renewal in the church cannot be denied,” Archbishop Hughes said. “The personal struggle that marked his life was severely complicated by the way in which authorities in Rome, during the papacy of Pope Leo X, treated him. A helpful place to begin is to note the need for both faith and repentance.”

Bishop Michael Rinehart, head of the Texas-Louisiana Gulf Coast Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, said there was “a spirit of ecumenical hospitality right now that we need to enjoy while it is happening.”

“Luther did not want to leave,” Bishop Rinehart said at the March 25 gathering. “He was bold, he was blunt, he was vulgar and mistakes were made, but he really didn’t want schism. He wanted to reform the church he loved.”

Bishop Rinehart said the 2017 anniversary naturally will elicit media coverage that may attempt to distill the reasons for the split and ask questions with a false premise: Why do Lutherans and Catholics hate each other?

“They don’t,” Bishop Rinehart said. Rather than “drive a wedge in Christendom,” he said, the commemoration could be “an opportunity to have conversation and bury the proverbial hatchet?”

Two of the concrete signposts of the fruitfulness of international dialogue, Archbishop Hughes said, are the 1999 joint statement by Catholic and Lutheran leaders on the doctrine of justification, and another landmark statement, issued last July, called “From Conflict to Communion.”

Luther had railed against the church’s practice of selling indulgences as a way of doing good works that would lead to salvation. The 1999 declaration on the doctrine of justification, which explains how people are justified in God’s eyes and saved by Jesus Christ, expressed a consensus that this is not an issue that divides Catholics and Lutherans.

Bishop Rinehart quoted the key phrase: “Together we confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works.”

“We are created for good works,” Bishop Rinehart said. “We’re not saying ‘by’ good works but ‘for’ good works. We can say this together as one.”

Last year’s document, released by the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and the Lutheran World Federation, offered five “ecumenical imperatives” for jointly commemorating the 500th anniversary in 2017 of the publication of Luther’s theses:

— Begin from the perspective of unity and not from the point of view of division.

— Be transformed by the encounter with each other and by the mutual witness of faith.

— Commit ourselves to seek visible unity, to elaborate together what this means in concrete steps.– Jointly rediscover the power of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

— Witness together to the mercy of God in proclamation and service to the world.

Bishop Rinehart recited the creed, which he said Catholics and Lutheran can say together.

He said Lutherans and Catholics “believe in the real presence of Christ” and “have a responsibility to witness to the transforming love of Christ. … It’s OK to disagree, but what the world needs to hear is the message of Christ.”

Archbishop Hughes said it was important to note that Pope Hadrian, who succeeded Pope Leo X, acknowledged in 1522 that “abuses, sins and errors” were made by church authorities in dealing with Luther.

In the past 50 years, Archbishop Hughes said, progress has been made “in our mutual understanding of the sacrament of the Eucharist. Lutherans refer to this as the Lord’s Supper. We have come to acknowledge that both Lutherans and Catholics believe in the real presence of Christ in this sacrament, even though each explains that presence in a significantly different way.”

There still are obvious doctrinal disagreements: the ordination of women, married priests and the sacramentality of holy orders. The Lutheran Church approved a resolution in 2009 to allow gays in “publicly accountable, lifelong, monogamous same-gender relationships” to serve as pastors. It also permits pastors to preside over same-sex marriages in states where they are allowed by civil law.

About those differences, Archbishop Hughes said: “Authentic ecumenism is always rooted in addressing truth with charity. We need not only to be explicit about what we have been able to recognize we believe in common, but also what it is we still need to address if we are going to realize the Lord’s priestly prayer at the Last Supper that we all be ‘one in him even as I am one with the Father.'”

The forum was sponsored by Interfaith Communications International in cooperation with the Archdiocese of New Orleans.

***

Finney is executive editor/general manager of the Clarion Herald, newspaper of the New Orleans Archdiocese.

PREVIOUS: Atlanta archbishop will sell new residence at center of controversy

NEXT: Court declines cases eyed over same-sex marriage, campaigns, executions

Just to be clear: Evangelical Lutherans (ELCA), Missouri Synod Lutherans (LCMS), Wisconsin Synod Lutherans (WELS) and all the little Lutheran off-shoots have different ideas about doctrine. To say “The Lutheran Church” allows for women and homosexuals to serve as pastors and to preside over homosexual marriages is misleading and incorrect – as any statement about doctrine blanketed by “The Lutheran Church” would be. We are not in agreement about many of these kinds of doctrine.