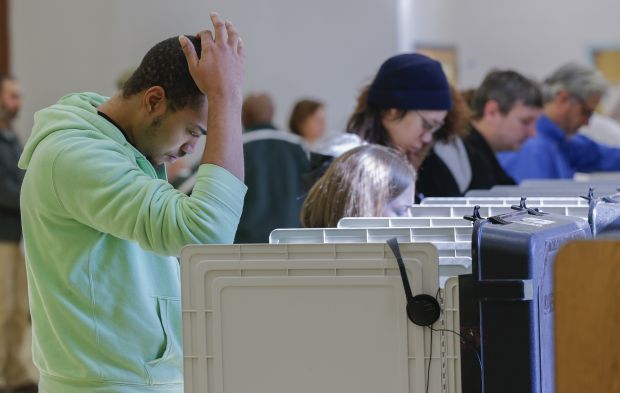

WASHINGTON (CNS) — On a day when Americans are given the opportunity to exercise a right that people in other parts of the world are still fighting for, many of them have chosen, and continue to choose, not to vote.

Though this may appear to indicate a sense of apathy among the U.S. public, the issue of decreased voter turnout in U.S. elections has diverse roots and illustrates more about Americans than just their general feelings toward politics.

Before the Nov. 4 midterm elections, the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press estimated that less than half of voting-age adults would vote. Although the official turnout numbers have not yet been calculated, this prediction follows a trend of declining voter numbers since President Barack Obama’s election in 2008.

[hotblock]

Midterm elections, however, have historically elicited a weaker response from the public than presidential elections. In a June 2014 report, the Pew Research Center showed that 51 percent of the public voted in the 1948 presidential election while 41 percent voted in the 1950 midterm election. Though the difference between these numbers has fluctuated over the years, the importance of the presidential election has not.

“There is a public sentiment that the midterm election is less important, because we’re not voting for president,” Dan Birdsong, a political science lecturer at the University of Dayton, Ohio, said in an interview with Catholic News Service. “Part of that is, I think, a modern construction around the president being the major player in politics. And so the public puts a different level of significance on the race for president than they do for midterms and the national media and other local media tend to not cover it as much.”

Factors such as age, gender, race, religion and socioeconomic status weigh heavily in the voter turnout process. While it may not be surprising that these components affect who, and what party, people vote for, they also can play a large role in whether people vote at all.

Steve Woolpert, the dean of liberal arts and a professor of politics at St. Mary’s College of California in Moraga, said increased economic disparity and polarization among constituents have caused voters to lose “a sense of the common good” and opt not to participate in the democratic process. He contrasted this with the public’s political involvement in the 1950s, when voter turnout peaked in part because of a sense of unity brought about by the public’s general support of U.S. involvement in World War II.

“Fragmenting loyalties, polarization and declining confidence in public institutions, I think, are all contributing to … a general sense that our sense of responsibility to one another and shared purposes aren’t as pronounced as they have been in other times,” he said. “People then lack confidence in the government and become more apathetic about participating and deciding who should be a part of it.”

Today, policies concerning abortion, contraception and same-sex marriage — all of which the Catholic Church opposes — have come to the forefront of many political debates, placing Catholic voters at the intersection of church and state. In the 2012 presidential election, a Gallup poll indicated that the Catholic vote closely followed the national vote.

E.J. Dionne, Washington Post reporter and professor of public policy at Georgetown University, said the diversity among Catholics, which creates such a similarity to the national constituency, can create marked differences in how they vote.

[hotblock2]

“There are a certain number of Catholics who are kind of cross-pressured by issues,” he said. “You have Catholics who are both pro-life and strongly pro-social justice. Some Catholics resolve that dilemma on one side or the other, but for many Catholics, they’re often torn between the parties on one set of issues versus the other set of issues.”

Sister Simone Campbell, a Sister of Social Service, who is executive director of the Catholic social justice lobbying group Network, participates in nationwide bus tours to encourage people to vote. Catholics in particular, she said, have a duty to do so.

“It’s in keeping with our faith,” she said. “We know our faith calls us to community and the way, in our nation, that we build a community and a diverse society is through the democratic process.”

Though Sister Simone does not advocate a particular political party or ideology when she encourages people to vote, she said she thinks Catholics should use church teachings as a guide.

“I think we have to look at the entire social teaching that we’ve got,” she said. “We have to look at the whole perspective of what supports human dignity … (and) make choices about who gets us closest to creating the kingdom of God.”

The solidarity of the Catholic vote, according to Woolpert, has weakened over the years as the Catholic community has become “unsure of its own identity.”

“My experience at a Catholic college is that Catholics have a hard time understanding what it means to be Catholic in the 21st century,” he said. “There’s a spectrum … of understanding what it means, it’s not a single unified point of view. And so, within the Catholic community, there are pretty strong differences about what Catholic identity can and should mean.”

Birdsong said he feels that there is a better indicator of how people vote than people’s religious preferences. “Their religiosity — so how much they believe in the Bible, if they believe it’s … the literal word of God (and) how often they attend (church)” is a stronger signifier, he said.

Woolpert agreed that there is a disparity among Catholics in how they vote.

“People have more than one identity. They’re not just Catholic,” he said. “There are all these crosscutting components to a person’s political identity and being Catholic is probably less primary in that constellation than used to be the case.”

PREVIOUS: Ruling sets up possible Supreme Court round on same-sex marriage

NEXT: Look to his history to understand ‘pope of surprises,’ cardinal says

Share this story