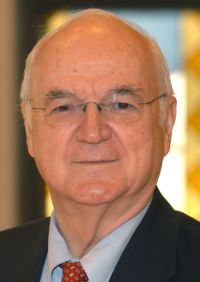

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Father Richard P. McBrien, a retired professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame and who was chair of the university’s theology department for 11 years, died Jan. 25 at age 78 in his native Connecticut.

A Jan. 25 announcement by the university said Father McBrien had died after a long illness, but did not specify the cause of death.

A wake and visitation for the priest was scheduled for the afternoon and evening of Jan. 29 at the Church of St. Helena in West Hartford, Connecticut. His funeral Mass was to be celebrated Jan. 30 at the same church. Notre Dame said a memorial Mass would be celebrated on its campus in the coming weeks.

[hotblock]

In addition to his teaching, Father McBrien wrote 25 books as well as a weekly syndicated column, “Essays in Theology,” for the Catholic press for nearly 50 years.

His writings often raised hackles among Catholics from the pews all the way to Rome.

“While often controversial, his work came from a deep love of and hope for the church,” said a Jan. 25 statement from Holy Cross Father John Jenkins, Notre Dame’s president.

Ordained in 1962 as a priest for the Archdiocese of Hartford, Connecticut, Father McBrien joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1980. He also was a past president of the Catholic Theological Society of America and a recipient of its John Courtney Murray Award for “outstanding and distinguished achievement in theology.”

Among his books is “Catholicism,” first published in 1980 with a study edition issued shortly thereafter, plus a thoroughly revised edition in 1994.

In 1985, the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Doctrine praised the “many positive features” of the book but criticized its treatment of some points of church teaching and called for clarification and revision of several elements it found “confusing and ambiguous” or “not supportive of the church’s authoritative teaching as would be expected” in such a book.

After the 1994 edition was published, the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith asked the U.S. bishops to look into it. A staff review said the new edition gave insufficient weight to church teaching in some areas, including homosexuality, contraception and women’s ordination. It questioned use of the book as a text for beginning theology students, adding the new edition “had not corrected the ambiguities identified” in the second edition. Father McBrien criticized the doctrinal committee for turning down his request for a formal doctrinal dialogue he sought.

Other books of Father McBrien’s include 2008’s “The Church: The Evolution of Catholicism”; 1997’s “Lives of the Popes: The Pontiffs From St. Peter to John Paul II”; 1996’s “Responses to 101 Questions of the Church” and 1995’s “Encyclopedia of Catholicism,” both of which won Catholic Press Association book awards for best popular presentation of the Catholic faith; and 1992’s “Report on the Church: Catholicism After Vatican II.”

A St. Francis de Sales Award finalist in 1993, Father McBrien received a certificate in 1991 for the 25th anniversary of his syndicated column.

Not that the columns were without controversy. Some readers of diocesan Catholic newspapers sought to have the priest’s column pulled from their pages.

One bishop, then-Bishop James P. Keleher of Belleville, Illinois, canceled it — the first time he said he had ever intervened as publisher in the business of his diocesan paper. “After many years of difficult reflection on the matter,” he said at the time, he pulled the column as “chief teacher of our local church,” because he felt it “frequently challenged what I want to be communicated to my people.” His decision prompted a published disagreement from the editor and a host of letters, most of them against the move.

Father McBrien weighed in on many topics affecting the church.

At a 1993 conference in Chicago, he said that without diminishing the pain suffered by victims of clergy abuse, those who claim that “we are the church” must address the injustices committed against those who actively minister and work for the church. Calling his approach a “consistent ethic of justice,” Father McBrien said the church must “practice in its own household what it preaches to others.”

In a 2002 address, Father McBrien said clergy sexual abuse was caused by deeper, compulsive and addictive behavior and by the “mystery of evil.” He said some Catholics insist that the crisis was caused by lack of fidelity to church teachings on human sexuality and that offenders are homosexuals encouraged by liberal seminary faculties.

If dissent were the cause of sexual abuse, he argued, why were “orthodox priests” accused of engaging in it? And if sexual abuse was linked with homosexuality, “what evidence is there that liberals are more inclined to be gay?” he asked.

During a 1992 talk in Indianapolis that drew seven times its expected turnout, he criticized “current discipline on obligatory celibacy and the ordination of women,” and challenged Catholics to take far more seriously the teachings of the church on social justice, service, evangelization and other aspects of Christian life. “I know I will disappoint those looking for heresy,” Father McBrien said. “I shall try not to disappoint those looking for substance and for hope.”

At a 1991 conference in Washington in the wake of political machinations in the former Soviet Union, he said there had been a coup of sorts in the Catholic Church. It was “too close to be denied, and too important to be ignored,” he said.

“We Catholics have been living these past 13 years through a prolonged, slow-motion coup of our own against the reforms of Pope John XXIII and the Second Vatican Council,” Father McBrien added. “Although no phone lines have been cut and no one placed under house arrest, it is a coup nonetheless, fueled by the ideology of the defeated minority at Vatican II and their heirs.”

PREVIOUS: March shows youth, growth and energy of pro-life movement

NEXT: Former senator’s daughter discusses gift of life, sister Bella’s story

Share this story