NOTRE DAME, Ind. (CNS) — Murdered Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero is held up as a beacon for the poor and oppressed, but scholars who see momentum in his sainthood cause say his conversion to this dogma was a slow process.

NOTRE DAME, Ind. (CNS) — Murdered Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero is held up as a beacon for the poor and oppressed, but scholars who see momentum in his sainthood cause say his conversion to this dogma was a slow process.

It’s a common narrative that Archbishop Romero had a sudden conversion from a quiet, cerebral archbishop to one whose outreach to the poor and disenfranchised led to his death, but Damian Zynda, an Archbishop Romero researcher who is a faculty member with the Christian Spirituality Program at Jesuit-run Creighton University, argues that transformation happened over the course of many years.

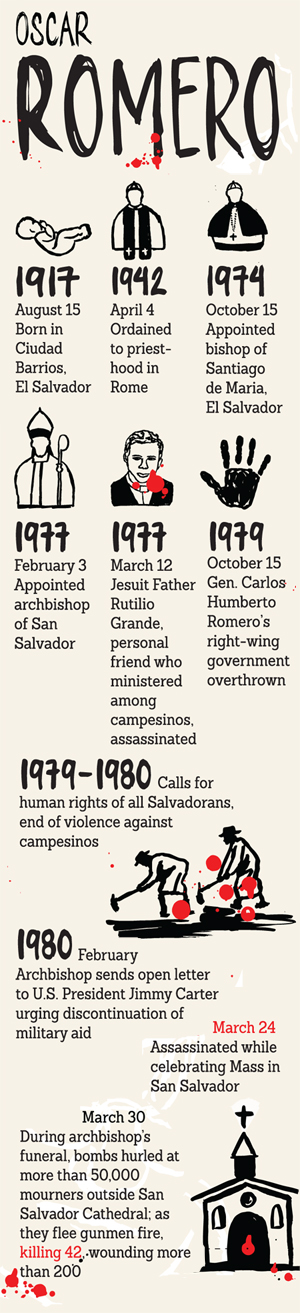

Scholars see a significant shift in the archbishop’s activism after the 1977 assassination of Father Rutilio Grande, a progressive Jesuit priest and friend of the archbishop who had been an unapologetic critic of what he called El Salvador’s oppressive government.

But Zynda and other researchers suggest that event was only a trigger, and that his true evolution resulted from a series of conversions that occurred throughout Archbishop Romero’s life.

The sainthood cause for the archbishop, who was shot and killed March 24, 1980, as he celebrated Mass in a San Salvador hospital chapel, appears to have momentum.

A panel of theologians advising the Vatican’s Congregation for Saints’ Causes voted unanimously to recognize Romero as a martyr Jan. 8, and declared that the archbishop had been killed “in hatred for the faith.”

The Congregation for Saints’ Causes must now vote on whether to advise the pope to issue a decree of beatification. A miracle is not needed for beatification of a martyr, though a miracle is ordinarily needed for his or her canonization.

Archbishop Romero had “small conversions that led up to and prepared him for this experience when Rutilio Grande was assassinated,” Zynda told Catholic News Service.

Zynda was among several scholars CNS interviewed during the annual International Conference on Archbishop Oscar Romero at the University of Notre Dame in September.

“There is no doubt that the Grande event was profound,” said Michael E. Lee, associate professor of theology at Jesuit-run Fordham University. “But I think we’ve come to understand more and more how that was … a tipping point, a capstone, a completion of a long process that in many ways we can say was lifelong.”

[hotblock]

“Conversions happen in moments of being aware of grace and responding to grace in our humanity,” Zynda said. “Romero, when he was 13, heard the call to grace to go to the seminary, (then) to the priesthood. He was very faithful.”

Following his 1942 ordination at 25, then-Father Romero began doctoral studies in Rome and focused on Jesuit Father Luis de la Puente, a 16th-century Spanish theologian, but was called back to El Salvador by his bishop before he could finish his degree.

In El Salvador, he became a devoted priest who plunged himself into his mission and ministry, Zynda said. “He is an academic at heart with a very sharp mind, someone who is very generous to God within the context of his culture and his own psychological makeup and he becomes an isolated workaholic.”

With no sense of collaboration or delegation, Father Romero frequently burned himself out and required a series of respites in Mexico, where he eventually entered into analysis in the early 1970s with a therapist who told him he had an obsessive-compulsive personality, she said.

“Little by little he begins to understand the ideology of his woundedness,” Zynda said. “And instead of him rejecting that, he embraced it. And he began to see grace at work in his own woundedness.”

In Archbishop Romero’s personal journals, he talks about that moment as one of the most pivotal of his life, “because it helped him to understand where he had come from, what his wound was, which I make the case that he never felt himself (to be) lovable or capable of loving,” she said. “So we start to see him practicing new behaviors when he comes back from that.”

Following his appointment as auxiliary bishop of San Salvador, he began to form sincere bonds with friends for the first time in his life and he started to take more personal time away from work, showing a slow evolution, Zynda said.

Though Archbishop Romero was raised in an economically depressed family and worked in a gold mine to support his seminary studies, he mainly worked in clerical positions as a priest. It was not until he was appointed bishop of the Santiago de Maria Diocese that he truly understood the suffering of the poor working on the coffee plantations in his country, Lee told CNS.

“Here was re-engagement with a pastoral reality of suffering, injustice, malnutrition and just tragic circumstances,” Lee said. “That moment opens him up to think through, ‘What does it mean to be a Christian? What does it mean to be a pastor? What does it mean to be church in the world today in light of suffering like this, in light of injustice like this?'”

While Archbishop Romero was undergoing a steady conversion, his reputation remained as someone who would not challenge the government in El Salvador or the wealthy power structure, said Julian Filochowski, chairman of the Archbishop Romero Trust in London, which was launched in 2007 to raise awareness about the murdered justice advocate’s life and ministry.

The Salvadoran government welcomed his February 1977 appointment as archbishop, but Archbishop Romero’s conservative reputation concerned many progressive priests, who feared he would suppress their commitment to the poor under liberation theology that had emerged throughout Latin America.

A few weeks later, Father Grande was gunned down on his way to Mass. Archbishop Romero traveled to the church where his friend’s body had been laid out and prayed with impoverished local farmers who told him stories about their suffering.

He emerged as the fiery champion of the poor and oppressed, who used the pulpit to denounce actions of the government, death squads in his country, violence from the outbreak of civil war and military occupation of churches, Filochowski told CNS in an interview at Notre Dame.

“So, the three years of his tenure as archbishop were three years of intensifying conflict in his preaching,” he said. “He spoke the truth, he took the word of God and he unpacked it and he made it real for his people and his poor, and he would make it relevant to their lives and their suffering.”

Archbishop Romero knew his actions endangered his life, but his gradual evolution as a true man of God allowed him to embrace the consequences that ultimately took his life, said Margaret Pfeil, associate professional specialist in theology at the University of Notre Dame.

“I think Romero had an understanding of the call of Christian discipleship as entailing ongoing conversion,” Pfeil told CNS. “So I think he understood holiness in that light.

“His desire was not to be edified as a saint himself, but rather to journey with people toward God and in God.”

PREVIOUS: New York’s French community offers prayers for victims of Paris attacks

NEXT: Novena aims to unite Catholics in prayer mark Roe v. Wade anniversary

Share this story