WASHINGTON (CNS) — Religious liberty is “the most fundamental freedom in society” and it is at “the very core of the human condition,” attorney and scholar Joseph Weiler told an audience at The Catholic University of America in Washington.

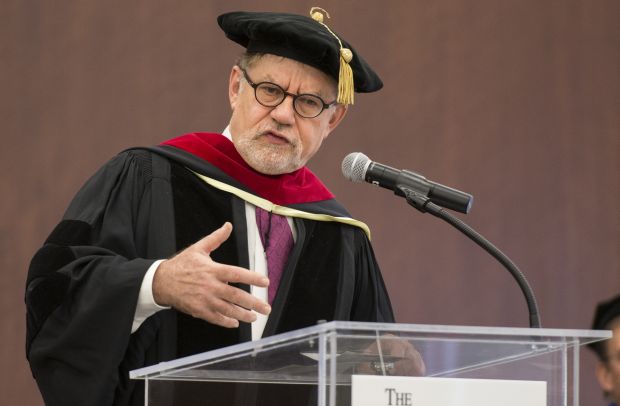

He gave a lecture at a ceremony where he was presented an honorary doctorate of theology by the university.

In attendance were John Garvey, the university’s president, and several members of its academic faculty at the March 19 event hosted by the School of Theology and Religious Studies.

[hotblock]

In honoring Weiler, the university cited his lifelong contributions to the cause of religious liberty, scholarship on Judeo-Christian morality in European public life, and the continued development of Catholic-Jewish relations in the Western world.

Weiler, born in 1951 in Johannesburg, South Africa, is the Joseph Straus professor of law at New York University. He also is the European Union Jean Monnet chaired professor, co-director of the Jean Monnet Center for International and Regional Economic Law and Justice, and president of the European University Institute, based in Florence, Italy. He is the author of several works relating to law and the European Union.

Though he has received many honorary doctorates in his life, Weiler admitted before the ceremony that this one would be his first in theology.

Reading his acceptance speech from two worn and tattered index cards, Weiler recalled how the previous morning at the National Gallery of Art he was thinking about what to say.

While reflecting upon viewing a painting of Daniel in the lions’ den that morning, Weiler joked, “I was undecided if I was a Daniel in a den of lions or a lion in a den of Daniels.”

Weiler immediately transitioned to his prepared lecture, “Sanctity and Morality in the Public Square.”

[tower]

The speech focused on a pair of addresses given by Pope Benedict XVI, one of which was to the academic world given in Regensburg, Germany, and prompted a wave of Muslim indignation and led to mass demonstrations in some countries. The pope had cited a medieval description of the teachings of Islam’s prophet Muhammad as “evil and inhuman.”

Later, Pope Benedict offered his regret, saying he was “unfortunately misunderstood,” because he was not agreeing with the polemical criticism of Islam. The pope emphasized his “profound respect” for Muslims.

“It seems in the field of religious discrimination, Christian blood seems to be the cheapest,” Weiler commented, noting that the response to the address “cost the lives of not a few Christians around the world.”

His lecture addressed how issues of morality and faith are treated in the modern public square, and particularly in the context of secular democracies.

“You can have Che Guevara,” the Cuban revolutionary, or any other figure on the wall of a schoolroom, but not a religious symbol, he said. “Why should this be the case?”

In 2010, the scholar represented, pro bono, eight European countries in an appeal against the European Court of Human Rights edict that barred the display of a crucifix in Italian public schools. The court found that the ban violated the European Convention of Human Rights.

In contrast, Weiler also recounted the importance of “freedom from religion,” that is freedom from the coercion of the state in regard to belief.

[hotblock2]

“Democratic theory finds difficulty in explaining why that should be the case; in a socialist system, where there is a socialist majority, you can have socialist laws. … Every worldview is game for the democratic process and we don’t say there has to be freedom from any of those conditions. But we do say that there has to be freedom from religion.”

“Coerced religion is not what God wishes,” said Weiler. “Our ‘yes’ to God is only meaningful when freely chosen.”

Weiler also devoted a great deal of his time to the discussion of morality both with and without “divine revelation.”

In recounting Abraham’s discourse with God before the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Weiler speculated that Abraham’s plea to save the righteous in the city must have “made God realize that he had chosen well.”

Abraham knew the norms of justice even without revelation, according to Weiler, and “this is what the Christian brings to the public square.”

“The proof of the pudding is in eating it,” when it comes to morality for Weiler, who spoke of it in terms relating more to natural law than solitary religious revelation.

It is “an act of hubris for the religious person to claim that their morality has a deeper base” than that of common human reason, said Weiler.

In closing, Weiler discussed what he called “the two sources of sanctity,” the first being what is common to all people through reason and the second being that which is solely attainable through revelation, which he called “an additional type of piety.”

To explain this, he cited the practices of kosher and halal, which are absent in the Christian faith. Respectively, kosher and halal are dietary laws of the Jewish and Muslim faiths.

According to Weiler, when a child asks his parents why it is bad to murder, it is easy for the parent to explain why on both a reasonable and theological plane, but when a Jewish child asks why they cannot eat pork, “the parent must explain that this is a practices dictated to us by God … it unites us and identifies us.”

The latter, he said, is simply “a different type of expression” of faith.

In addition to his other titles and accolades, Weiler is also co-director of the Tikvah Center for Law & Jewish Civilization, director of the J.S.D. program of the New York University School of Law and His book “The Constitution of Europe: Do the New Clothes have an Emperor” has been translated into 10 languages.

PREVIOUS: Archbishop: ‘Use energy’ of Selma anniversary to heal today’s divisions

NEXT: Mother, daughter killed in crash recalled for devotion to faith, family

Share this story