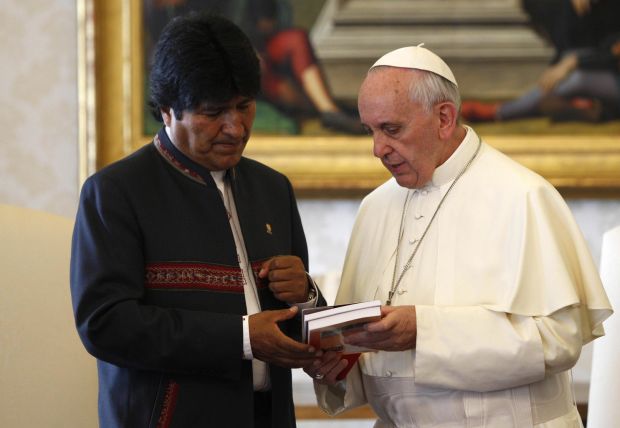

MEXICO CITY (CNS) — In October 2014, Bolivian President Evo Morales traveled to the Vatican-sponsored World Meeting of Popular Movements, an international gathering of grass-roots activists. On the trip, he met informally with Pope Francis for the second time — an encounter observers back in Bolivia saw as significant given the sour state of church-state relations since he became president in 2006.

It’s believed that during that trip, he proposed that Pope Francis visit Bolivia. Now the pope is scheduled to visit the country July 8-10, part of a South American trip in which Pope Francis will also visit Ecuador and Paraguay.

The trip, according to the observers, shows the overcoming of mutual suspicions between Bolivia’s bishops and Morales, who swept to power on an agenda of improving life for the country’s mostly indigenous population — but spooked elites and investors with talk of socialism and cozying up with Venezuela.

[hotblock]

Relations have improved to the point that bishops greeted Morales with an ovation at the conference’s April assembly, and the church is working closely with the foreign ministry in planning the papal trip.

“For the church, the arrival of the pope could be a grand opportunity for a new phase of relations with the government,” said Jose Rivera, press director for the Bolivian bishops’ conference. “There is some openness from the government party, and we expect that this will continue.”

The improvements, Rivera and other observers say, stem from the election of Pope Francis and the oft-spoken-of “Francis effect,” which has won over a previously antagonistic president.

“What we have seen since the start” — the pope’s election in March 2013 — “is a strong sympathy toward Pope Francis,” said Rafael Archondo, information director of the La Paz-based Agencia de Noticias Fides, a Jesuit-run news service. “Starting with Pope Francis’ actions, his discourse, Evo Morales immediately became quite enthusiastic with the change.”

People touch the foot of a statue of Christ during the annual Alasitas festival in 2013 in La Paz, Bolivia.(CNS/David Mercado, Reuters)

The visit offers an opportunity for Bolivia to bask in international attention for positive reasons — such as its unexpected economic success. Bolivia’s economy expanded more than 5 percent annually — among the best in the region — thanks to high prices for natural gas and minerals. The Bolivian government says extreme poverty fell from 38 percent of the population to 18 percent by 2103 in what is still South America’s poorest country. The government also has invested in social programs and infrastructure — the product of a partial expropriation of the petroleum sector, which swelled state revenues.

“There’s a general perception that on the economic level, Bolivia has experienced a golden age, mainly due to the high international prices of gas and minerals,” Rivera said. “Presently, the general opinion is that this age has ended (due to lower resources prices) and we did not take advantage of the good times.”

Still, it’s a political and economic situation few predicted for Bolivia and Morales, an indigenous Aymara and former leader of the country’s coca-leaf growers.

His style upon taking office raised questions. “He’s put his own supporters in the judiciary and been ruthless in neutralizing opponents,” The Economist said in an article.

Morales also speaks of “Pachamama” and mother earth, while encouraging the expansion of extractive industries, observers say.

He’s tended toward nationalism, but stayed somewhat pragmatic. Elites in the eastern lowlands — who agitated for increased autonomy — made peace with Morales, mainly because “there’s been enormous growth,”Archondo said.

“It’s been social-democratic in practice,” he said of Morales’ approach, “although they like this description.”

Morales won a third term last fall and remains popular, Archondo said, though his Movement Toward Socialism party — commonly known as MAS — lost spring elections in some of Bolivia’s departments, governmental entities similar to states.

The president has not always been popular with church officials, though.

Cardinal Julio Terrazas Sandoval, then archbishop of Santa Cruz, a city in the lowlands where Pope Francis will visit and celebrate Mass, had sharp exchanges with Morales. He told the Spanish publication Vida Nueva in 2010 that the president “presents himself as the one that will save all the world’s indigenous and … he has a personality almost at the same heights as other religious leaders.”

Cardinal Terrazas retired as archbishop in 2013, at age 77.

A woman carries figurines of Joseph and Mary after a 2011 Mass for the feast of the Epiphany in La Paz, Bolivia. (CNS/David Mercado, Reuters)

In 2009, Bolivia approved a new constitution, which created a secular state, causing concern among Catholic leaders over their work in education and role in the country. U.S. Maryknoll Father Stephen Judd said that, despite new education laws, the church role continues to be strong, along with the faith of ordinary Bolivians.

“It’s not a militant kind of Catholicism that adheres to the Western standards,” said Father Judd, a missionary in the city of Cochabamba. “But there is a strong religious sensibility in the Bolivian people.”

Catholicism in Bolivia includes characteristics such as an appreciation of the earth held by indigenous peoples, who comprise a majority of the population, Father Judd said. More than 70 percent of people in Bolivia profess Catholicism.

The church has played an important role in developing the country — and still does to this day — especially in the areas of health and education. Religious orders built the church in remote areas and “(took) over vicariates or prelatures, where there wasn’t a native leadership,” Father Judd said.

Many in the church worked with the grass roots, with indigenous peoples and on human rights, Father Judd said. But relations with the Morales government started off sour — perhaps, he said, because the bishops attempted to mediate conflicts prior to Morales’ election and ended up on the side of the government — but “not intentionally so.”

“It’s been a lot of missed opportunities on both sides. … It shouldn’t have been an adversarial relationship in any way,” said Father Judd. “The church at the grass roots has already given witness to human dignity, the history of the social movements.”

Observers see signs of pragmatism playing out in regards to religion.

“More than having a state that is neutral toward religion, what we have is a state that perhaps is encouraging various positions,” Archondo said, pointing to Bolivia continuing to celebrate the feast of Corpus Christi as a national holiday, along with days such as the Andean new year. “It’s a sort of strange secular state.”

***

Editor’s Note: David Agren will be traveling to Bolivia to help cover Pope Francis’ visit. You can follow him on Twitter, @el_reportero.

PREVIOUS: Pope helps homeless, poor in Rome make pilgrimage to Shroud of Turin

NEXT: French Catholics want countries to quit buying oil from Islamic State

Share this story