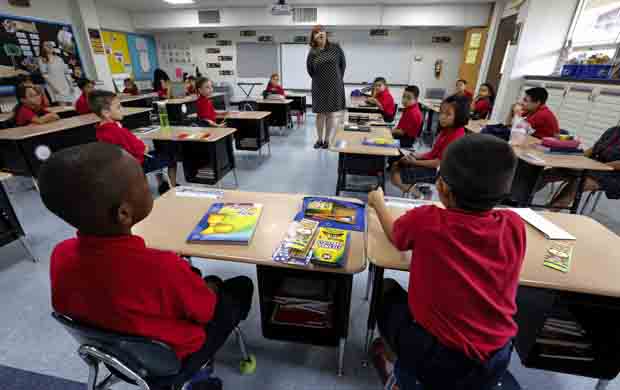

WASHINGTON (CNS) — In trying to find a “typical” Catholic school for Pope Francis to visit in the United States, planners found Our Lady Queen of Angels in New York.

But given the diversity of situations of U.S. Catholic schools, the inner-city Harlem school will give the pope only a glimpse of the wide variety of models of Catholic education available in various parts of the country.

Our Lady Queen of Angels, for example, is part of a nonprofit partnership that operates half a dozen schools for the Archdiocese of New York. But other schools are in dilapidated buildings, scrambling for funding, staff and students. Others, especially in suburbs in the South and West, are bursting at the seams in new structures.

In a series of Catholic News Service visits to parishes across the country over several years, reporters saw traditional parish schools in California and Mississippi and merged or regional schools in New Jersey and Wisconsin.

Like their counterparts elsewhere, most elementary schools include grades kindergarten through eight, and many are beginning to offer pre-kindergarten classes. Many schools are still affiliated with parishes but that is hardly the only model anymore. There are regional elementary schools, school consortiums and school networks.

Today’s Catholic schools seem to have their feet in two worlds: They are steeped in long-standing tradition, while seeking ways to adapt to current needs.

The National Catholic Educational Association report on schools for 2014 counted 5,368 elementary and 1,200 secondary Catholic schools. Since the previous year’s report, 27 new schools opened; 88 schools consolidated or closed and 2,044 schools have a waiting list for admission.

Many schools — as a result of parish mergers — also have merged entities. St. Francis of Assisi in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, for example, is a new parish, created after the city’s six parishes were all closed 10 years ago. Its consolidated school operates on two campuses: an elementary school campus — preschool through fourth grade along with the school’s central office — is at one location and the middle school (grades five through eight) is at another.

Holy Savior Academy in South Plainfield, New Jersey, opened in 2011 after four schools in the Metuchen Diocese closed because of declining enrollment. The merged school is on the property of the former Sacred Heart School, part of Sacred Heart Parish, 30 miles outside of New York City.

Merged schools, like traditional parish schools, still face the challenge of the high cost of operation and trying to keep tuition costs within reach of middle and working class families. Administrators try to offset costs with fundraising efforts but often that even that has a price that parents need to pay if they don’t raise the required funds.

Parents often say they remain committed to the schools even with the expense because they see the importance of a Catholic education, particularly the quality academics and values.

But the commitment isn’t always synonymous with involvement, something that is inconsistent from school to school. In some schools it happens simply from a longtime sense of community spirit. Other schools almost force it by requiring parent volunteer hours and mandatory meetings.

Holy Family School in South Pasadena, California, might set the high bar at one end the parental-involvement scale.

Principal Frank Montejano said “so many families want to be in the school that they get involved before their kids are school age.” He also attributed parental involvement to the former pastor who “created an atmosphere where people wanted to come here. It’s the envy of other schools because parents are very involved and there’s a very strong parish life, with lots of activities.”

He said when he needs help, he just sends out an email. When the play area needed updating, for example, he said parents came to him with sophisticated plans for the space, including one parent who designs theme parks for a living.

“That kind of thing happens all the time,” he said.

But it’s not the norm.

Franciscan Sister Mary Ann Tupy, principal of St. Francis School in Greenwood, Mississippi, said her “biggest dream is to get parents to see this as their school and take on some of the responsibilities.”

This is from the woman who is also the school’s bookkeeper, janitor and fundraising coordinator. She said she worries every day whether the school can stay open.

“The people are dear. You wish you could do more,” she said.

When the school first opened in 1951 as a Franciscan outreach to the area’s impoverished black families, students and parents did all they could to keep the school functioning.

Georgette Griffin, one of the first students at the small rural school, said: “All of us did everything. We didn’t know what janitors were! We polished those floors. We always did everything.”

She said one building housed the church, the school and all parish ministries, which included a credit union, training for GED high-school equivalency exam, social services, skating, square dancing, and a grocery store and doughnut shop.

Today, the school has few modern touches. In the hallway, there is a box of used uniforms available for sale for $1 per item and a box of flashlights because the power goes out pretty regularly. Sister Mary Ann said the school does not have an alumni group and has not been able to tap into local community support. Its enrollment now includes many Hispanics, the children of immigrants who come to Greenwood to work in commercial catfish farms and agriculture. Many send part of their income to family in their home countries.

“There long has been a mentality in town that St. Francis will take care of everyone. Now we need them,” the principal said. “I fear the day when we can’t take care of things.”

***

Contributing to this story were Dennis Sadowski in South Plainfield and Patricia Zapor in Manitowoc, Greenwood and South Pasadena.

PREVIOUS: A totem pole and a papal encyclical symbolize opposition to coal trains

NEXT: Parish views: From do-it-all pastors to 100 ministries to guide

Share this story