BOSTON (CNS) — In a fairly industrial-looking part of South Boston, four women gathered in a classroom at the Notre Dame Education Center.

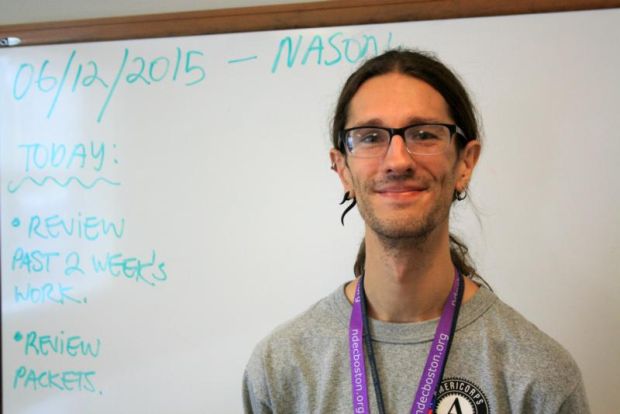

It was time for their twice-per-week math lessons with AmeriCorps volunteer Nason Heywood, 29.

The students were reviewing addition and subtraction concepts, working through the sometimes complicated processes of carrying 10s and borrowing. Heywood posed problems at the white board.

Heywood is wrapping up his second year at the Notre Dame Education Center, where he has taught basic math and English skills to mostly immigrant adults. The experience has changed his life.

[hotblock]

Like virtually everyone who dedicates an entire year or more to full-time service, whether it is through the AmeriCorps partnership with the Notre Dame Mission Volunteers or one of the 200 other programs affiliated with the Catholic Volunteer Network, Heywood is leaving the program a different person than he was before he started.

Heywood, for one, never expected he would be a teacher. Sure, his parents had told him for years that he should be one — with the advice becoming increasingly more insistent as an alternative to his life as a “bum painter” — but Heywood demurred, somewhat stubbornly, he will admit.

After seven months focusing on painting and sculpture, he joined AmeriCorps, first applying to be an art teacher at the Notre Dame Education Center. By the time he interviewed, the position was filled. He eventually accepted an assignment to primarily teach basic math and enjoyed it so much decided to extend his AmeriCorps contract into a second year.

This past spring, Heywood enrolled at Lesley University for a doctoral program in special education, planning a long-term career in exactly what he thought he’d never do.

More than 3,100 long-term volunteers served at sites affiliated with the Catholic Volunteer Network during the 2013-14 program year, the latest year for which data are available.

These mostly 20-somethings turn to a year or more of service to follow bachelor’s degree programs or prompt a pivot from one job to another. Many programs are open to both men and women of all ages and all faiths, while some are limited to younger adult volunteers or just women.

The 200 programs that will be active in the 2015-16 program year span all regions of the United States and select locations abroad, where dedicated volunteers will come together to serve others and learn more about themselves.

[tower]

Natalie Brown is the development coordinator for Notre Dame Mission Volunteers. She said during the interview process with prospective volunteers, she stresses the idea that joining the program is not only going to be a year of service.

“A lot of people don’t realize it’s going to be a year for themselves,” Brown said.

Notre Dame Mission Volunteers is based in Baltimore and has program sites in 20 cities nationwide as well as a handful of international locations.

The organization was originally founded by the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur in 1992 to place volunteers in roles where they’d work alongside the economically disadvantaged, promoting literacy and education. Since they partnered with AmeriCorps when it launched in 1995, the program has expanded, maintaining a strong commitment to the Sisters’ original mission.

Like Heywood, Notre Dame volunteers often develop a passion for teaching. Others go on to be social workers, civil or human rights lawyers and shapers of public policy. That is not unlike the alumni of other Catholic Volunteer Network-affiliated programs.

In the Mercy Volunteer Corps, executive director Marian Uba compared her program’s impact to ripples in a pond.

“It’s really about putting a face to the poor and marginalized in our society and hoping that it connects with them (volunteers) in a meaningful way,” Uba said, adding that no matter the path they take in life, alumni of the one-year program know they have the ability to make change in a positive way.

Inspired by a 19th-century Irishwoman, Mother Catherine McAuley, founder of the Sisters of Mercy, and her commitment to follow Jesus through compassionate service, the Mercy Volunteer Corps was founded in 1978 “to address the needs of the poor and marginalized throughout the United States.”

Uba has served as the executive director for seven years, during which time the program has grown by about 50 percent. Now, close to 40 volunteers are selected to serve domestically each year;about four more serve in international locations. Their volunteer positions are in agencies with strong support to guide them through what can be a tough year, and they also are buoyed by the corps’ monthly team meetings.

“Some of them will see things they couldn’t possibly have imagined,” Uba said. “They may have done a week of service, but living in solidarity with the other is a much, much different experience.”

Teachings from the Sisters of Mercy justice curriculum add to a Mercy Volunteer Corps members’ experience. They get opportunities to participate in various events with the sisters. Volunteers this past year attended Ecumenical Advocacy Days and a climate march in New York City.

After their program years, a majority of program alumni stay engaged in social activism and find careers in education, social service and health care fields, Uba estimates. Many go on to graduate school for degrees in social work.

Like in many peer programs, some even accept full-time, paid jobs at their placement sites.

That’s a transition Brooklyn Vetter, 22, is preparing to take in St. Paul, Minnesota. Vetter, a graduate of Minnesota State University, has spent the last year working at The Lift Garage through the St. Joseph Worker Program, which is sponsored by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet.

The sisters have been responding to the needs in the community and serving neighbors since their order’s founding in France in 1650. The St. Joseph Worker Program took up that mission 14 years ago.

Vetter’s placement site, The Lift Garage, provides low-cost car repair for low-income Minnesotans.

“It was a barrier I had never really recognized,” said Vetter, whose father is knowledgeable about cars. Growing up in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, if Vetter had a problem, she would drive her car home and have it fixed for free.

Over the past year, Vetter has realized just how much of a crisis one breakdown can cause, putting people behind on rent, forcing them to miss work. “One car repair turns into something so much bigger than what it originally was.”

She was drawn to the St. Joseph Worker Program’s focus on an inclusive, broad definition of spirituality after struggling with her own connection to religion. Over the last year, Vetter has grown with the help of a spiritual mentor.

Living in an intentional community of other young women, all volunteers with the program, Vetter has enjoyed weekly “sharing of the heart” gatherings that ask each woman to say how the spirit loved her and how she loved the spirit.

The St. Joseph Worker Program is organized to teach these women “the two feet of justice” — direct service and systemic action.

Besides Vetter’s time working at the Lift Garage completing intakes, ordering parts and dabbling in fundraising efforts, she also lobbied state representatives on a bill that will allocate funding to nonprofits providing transportation.

Sister Suzanne Herder, director of the St. Joseph Worker Program, said most women selected for the program have an understanding of social justice, but many are at the “charity level.”

“They want to help people,” Herder said. “We move them to the next level, which is the caring level of journeying with the people.” This second stage, instead of seeking just to help the marginalized, seeks to empower them.

[hotblock2]

The women of the St. Joseph Worker Program, long after they finish their service years, remain connected to the organization that shapes their worldview. A majority have gone on to work for nonprofits and have found ways to continue in the spirit of service fostered by the Sisters of St. Joseph.

“They live that life of loving God and neighbor without distinction after they leave us,” Sister Herder said.

Imparting such values is a goal of many programs affiliated with the Catholic Volunteer Network.

Funded primarily by grants and member dues, the network provides a basic infrastructure to help even the smallest programs make an outsized impact. Its visibility provides a recruitment tool for programs, though they also benefit from their own website presence, word-of-mouth, volunteer fairs, churches and universities.

The combined recruitment work helps connect energized volunteers like Heywood and Vetter with communities that need them, which in turn gives them the chance to discover their own passions and strengths that will set them up for the rest of their lives.

***

Tara Garcia Mathewson is a freelance writer based in Boston.

PREVIOUS: Forgiveness at heart of healing after Ferguson violence, says archbishop

NEXT: Charitable works inspired by pope’s call to serve people on the margins

Share this story