WASHINGTON (CNS) — The breadth of President Donald Trump’s authority to limit refugees entering the United States will be fought in federal court and some of the legal challenges ultimately may end up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Several lawsuits have been filed challenging Trump’s Jan. 27 executive memorandum that suspended the entire U.S. refugee resettlement program for 120 days and banned entry of all citizens from seven majority-Muslim countries — Syria, Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Yemen and Somalia — for 90 days.

Another clause in the memorandum established religious criteria for refugees, proposing to give priority to religious minorities over others who may have equally compelling refugee claims.

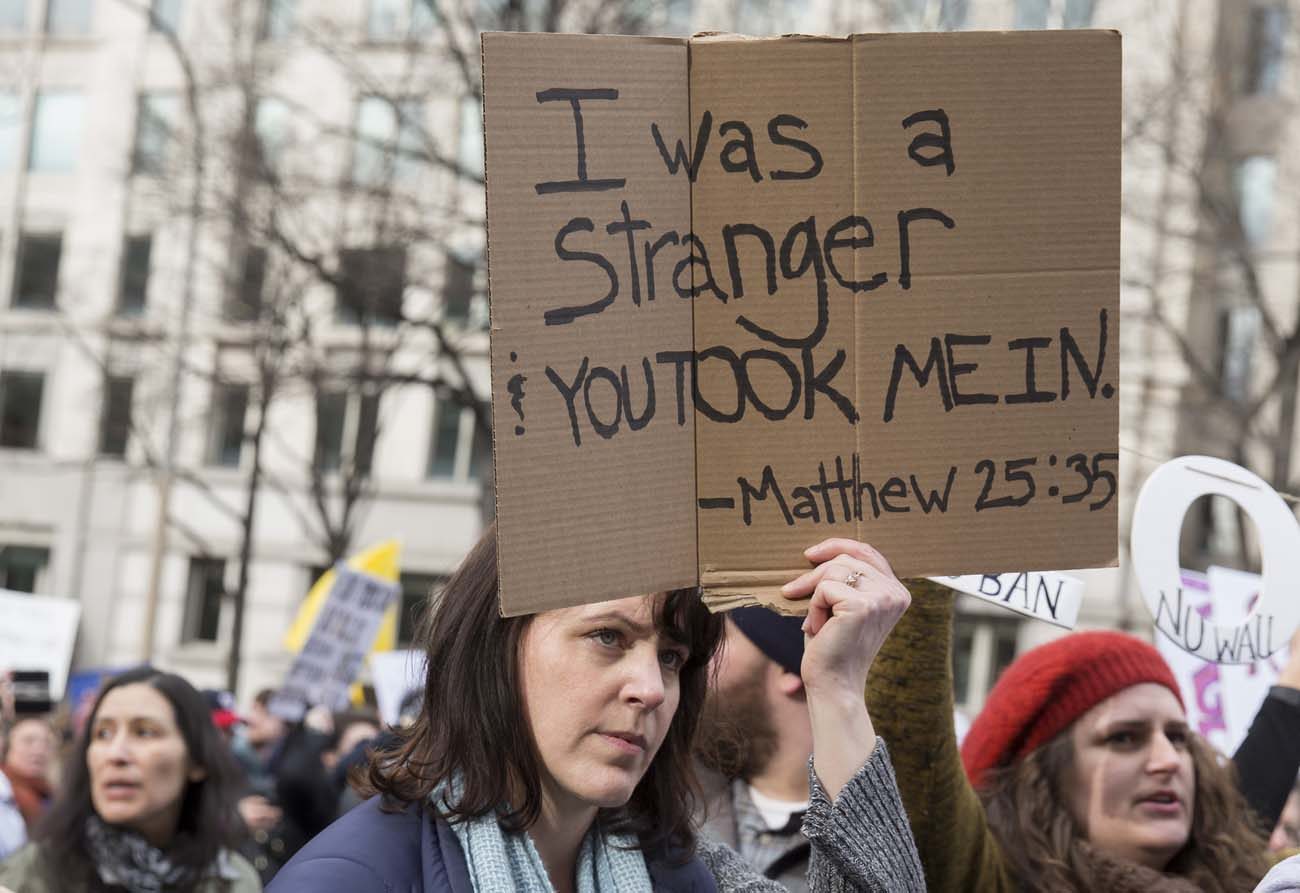

[hotblock]

In five of the earliest lawsuits, federal judges blocked the government from denying entry to anyone from the affected countries with a valid visa.

One decision came from U.S. District Judge Andre Birotte Jr. in Los Angeles, whose Feb. 1 order “enjoined and restrained” the government from enforcing the president’s memorandum against 28 plaintiffs from Yemen who have been held in transit in Djibouti since the president signed the document. Similar orders have come from federal judges in Boston; Seattle; Brooklyn, New York; and Alexandria, Virginia.

The court orders are short-term in nature and were issued in anticipation of the cases being argued by both sides during the next several weeks before any potential restraining orders are issued.

A statement issued Jan. 29 from the Department of Homeland Security said the U.S. Customs and Border Protection “began taking steps to comply with the orders.”

More lawsuits are expected and could encompass several parts of the law that govern presidential authority over who to admit and not admit to the U.S.

[hotblock2]

Attorney Charles Wheeler, director of the Catholic Legal Immigration Network’s Training and Support section in Oakland, California, identified one area of the law that allows the president to suspend the entry of “any class of aliens” if it determined that their entry “would be detrimental to the interests of the United States.” However, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 amended the law to prohibit any foreign-born national from being given preference because of their “race, sex, nationality, place of birth or place of residence.”

“The refugee issue is going to turn on whether (Trump’s action) specifically exempting Christians says that the intention of it is in fact to favor one religion over another,” Wheeler told Catholic News Service. “I think that makes (the action) much more vulnerable to equal protection challenges.”

Attorney Charles Roth, director of litigation at the National Immigrant Justice Center in Chicago, suggested that a half dozen or more areas of the law could be cited in any legal challenges to the executive action.

“One of the strong arguments is that the president’s statutory authority doesn’t allow him to make these sweeping rules about everyone from a particular country,” said Roth, who is Catholic.

The executive memorandum is vague enough that questions remain over the status of visa applications for refugees already in the U.S. versus those still outside of the country, Roth added.

“It feels to me that the president sees being tough on refugees is the symbolism he’s looking to have. This order doesn’t seem to be designed to be particularly dependable as a legal matter or particularly nuanced to achieve justice and fairness,” Roth said.

[hotblock3]

Despite the memorandum’s vagaries, Gemma Solimene, clinical associate professor of law at Fordham University’s School of Law, expects the government to defend it on national security grounds and deny that Muslims are being singled out.

Acknowledging that the law gives Trump broad discretionary powers with respect to entry into the U.S., she said she found the document “is clearly not well thought out, there isn’t a lot of guidance (for carrying it out).”

“If they were clearly serious on national security, there would be other things (in it) to actually have effect on these issues,” Solimene said.

She suggested that the memorandum could have justified its stance by including information about any attacks by foreign nationals from particular countries.

“The reason they made this a national security problem or under the guise of national security is because it is less challengeable. The government clearly has a lot more discretion when they say this is an issue of national security,” Solimene said.

Officials at the Migration and Refugee Services of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and Catholic Charities USA told CNS they do not plan to enter the legal fray, however.

William Canny, MRS executive director, said it is unlikely that Trump would rescind his memorandum so the agency will focus on making sure actions under the new policy address humanitarian concerns, such as family reunification whereby a child or parent is awaiting entry into the U.S.

“The majority (of cases MRS has handled) in recent years have been reunifying families. So now you have families separated (because of the memorandum) and anyone who is separated from family by distance and time … knows the pain,” Canny said.

Most of the people MRS has been resettling are women and children, “who for example witness the murder of their father and who are languishing in a camp and who have family to join here in the U.S. to help them, who can’t return to their country, who can’t find work or schooling in the country they’re in.”

“That’s who we take,” he said.

Canny urged federal officials to keep such needs in mind and complete the vetting of refugees as quickly as possible.

Dominican Sister Donna Markham, president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA, said her agency would avoid joining any lawsuits challenging presidential action, but would focus on making “people aware of what’s happening” with refugees that “is not in line with the Gospel.”

PREVIOUS: ‘Stand for What You Believe In’ is theme for national day of prayer

NEXT: U.S. archbishop visits Vietnam to show solidarity, offer support

It’s for 90 days. Life can be unfair at times. These 7 countries are the same ones that former President Obama indicated were hot-beds for terrorist activities. How do you know that intelligence wasn’t gathered indicating a potential threat? Terror attacks are on the rise all over the Western hemisphere. President Trump did not make any secret about this stance on protecting American citizens. Go to the UN and protest. Demand they do something about these horrible atrocities in these foreign governments in the middle east that allow their citizens in grave danger.