WASHINGTON (CNS) – The history of women and men religious in the United States is the history of American Catholicism and their archives reflect the rich role many played in weaving the fabric of the U.S. church, said a group of historians, scholars and archivists at a March 29 gathering in Washington to discuss religious order archives.

Archives particularly show the roles women religious played in the country’s education, hospitals, immigrant communities and social movements, they said, and yet there’s a danger of losing some of that history — as well as that of their male counterparts — as religious orders consolidate, convents merge or close, and their historical materials are discarded, lost or scattered.

When it comes to the records produced by the religious ministries of women religious, they tend to tell a richer story than official diocesan history, said Mary Beth Fraser Connolly, a panelist in “For Posterity: Religious Order Archives and the Writing of American Catholic History,” part of a daylong series of events at The Catholic University of America aimed at discussing the fate of religious order archives.

[hotblock]

Connolly mentioned the example of the official history of a parish school, where the priest is credited with its construction, but archives from women religious tell the story of how the women staffed the schools “for little to no salaries” and how they subsisted on other means of income to survive.

Connolly, continuing lecturer of history at Purdue University Northwest in Indiana, also gave the example of another “convent chronicle” she came across by an Italian immigrant, Sister Justina Sagale, who wrote about social settlement houses, the lives of Italian immigrant communities in Cincinnati as well as immigration laws that she felt negatively targeted Italians. Sister Sagale also told of an Italian teacher in one of the schools “who didn’t have his papers yet” and was worried about the new law.

The account “provided a more complex understanding of Catholic American history,” said Connolly, who has written about communities of women religious.

Another account from a group of women religious in Chicago mentions the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. assassination in 1968, but what’s interesting in the account, in terms of Catholic history, is that the women mention traveling across town at night, driven by a priest.

In a simple entry, it documents some of the changes that were taking place in the daily lives of women religious following the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, Connolly said. It shows how the women were given more freedom to visit family, to have contact with others, how nieces and nephews were now more involved in their lives, how the women could watch TV, and, in general, how they were having more contact with the outside world.

“Things are starting to change and that’s kind of nice and interesting,” Connolly said.

[hotblock2]

Carol Coburn, professor of religious studies at Avila University in Kansas City, Missouri, said that as someone who is not Catholic, getting a glimpse at the records, as she was researching, was an “amazing experience for me.”

“When we ask ourselves the question: What is the contribution of religious order records to the understanding of Catholicism? My answer is: everything,” she said.

Religious order records include information about demographics, customs, financial records, all found in constitutions, annals, memoirs, photos and correspondence that members of the congregations kept, and they “add immensely to history of American Catholic life,” she said.

“I would argue that to know the full history of American Catholicism, you have to know what religious orders were doing at any given historical point in time,” said Coburn, who studies and writes about American Catholic sisters.

When it comes to women religious, Coburn said, the records show that women religious led Catholics and non-Catholics “in some of the most significant social movements in cultural and political transitions we’ve experienced in the 20th century.”

Because they were highly educated, women religious created and maintained institutions, served as faculty administrators “and CEOs of their communities and institutions, long before the vast majority of American women worked in these in these leadership roles,” Coburn said. And they were participants, and in some cases, leaders in every major social movement since the 1960s, including providing treatment for HIV and AIDS patients, immigration, the anti-nuclear movement, violence against women and children, the environment, etc., Coburn said.

“This is part of all of our stories,” she added. “I am not Catholic, but this part of my story because it is integrated so thoroughly within the American milieu.”

While not everything in the records is important and sometimes focuses on the mundane, such as who was in charge of sweeping the back stairs and who named the convent dog, the archives have “potential to be gold mines for historians,” said Connolly.

[hotblock3]

Malachy McCarthy, archivist for the Claretian Missionaries Archives in Chicago, said that if historical materials contained in religious order records are not made available, an inaccurate story will get told and gave the example of a landmark study that didn’t paint an accurate picture of Latino Catholics in Los Angeles.

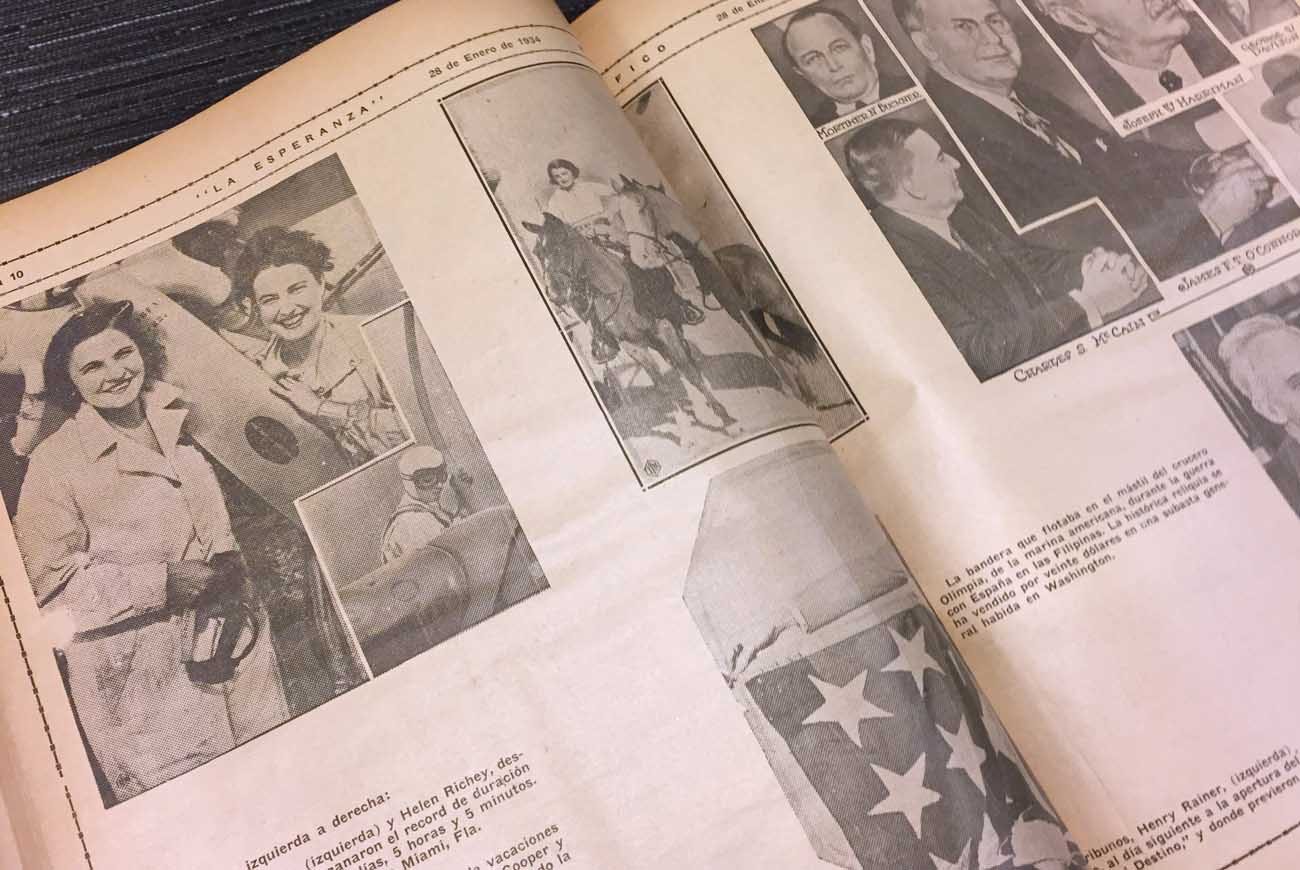

While the study, about Mexicans immigrating to Los Angeles from 1900 to 1945, painted a picture of Latino Catholics who didn’t make many public displays of their faith, Catholic records and publications show otherwise. The Spanish-language Catholic weekly publication La Esperanza, for example, showed the vigorous and very public life of the Latino Catholic community in Los Angeles, in stark contrast to what was said in the study, McCarthy said.

“It shows you what happens when you don’t have availability of sources,” he said. It also shows the consequences — incorrect information, which “becomes the canon,” he said.

PREVIOUS: Archbishop: Belarusians devoted to Fatima, still struggle with secularism

NEXT: U.S. Supreme Court examines pension plans of religious hospitals

Share this story