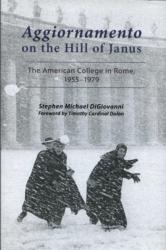

Msgr. Stephen M. DiGiovanni

(CNS photo/Robert Duncan)

ROME (CNS) — The Pontifical North American College has an important story to tell, and it is not one any official records will reveal: the tale of what daily life is really like at the U.S. seminary in Rome.

“We have to keep tons of ecclesiastical and official records, but that doesn’t tell the story of the banquets and the fun,” said Father Peter C. Harman, rector of the college, which is commonly referred to as the NAC.

As the seminarians return to Rome for a new academic year, a third-year student has been assigned the all-but-forgotten role of “house chronicler” with the task of making notes about daily life at the college.

The notes, Father Harman said Aug. 22, “aren’t opinionated; it’s not commentary.” They are meant to provide “a living record of the place.”

The revival of the job follows the publication of a book on the college’s history that drew largely on the records kept by previous house chroniclers.

“Aggiornamento on the Hill of Janus: The American College in Rome, 1955-1979” by Msgr. Stephen M. DiGiovanni chronicles the years leading up to, during and immediately after the Second Vatican Council, which was held from 1962 to 1965.

[hotblock]

Msgr. DiGiovanni, who was part of the NAC class of 1977, told Catholic News Service that his book also “includes interviews with alumni and former faculty members, bishops, laypeople who work there, religious sisters; it deals with student and faculty minutes, notes of meetings, diaries, letters, all kinds of stuff that’s unpublished, and it’s rather intense.”

The book was the idea of a former rector, Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan of New York.

“Even the ordinary Catholic in the pew realizes that, between the 1950s and 1970s, something ‘radical’ happened to the church,” Cardinal Dolan wrote in the book’s foreword.

Understanding the changes, he wrote, is impossible “without comprehending those tumultuous decades from 1955 to 1979.”

In an interview at the Basilica of St. John the Evangelist in Stamford, Connecticut, where he serves as pastor, Msgr. DiGiovanni cited the disruption surrounding the reform of the Mass as one example.

(CNS photo)

The seminarians were “extremely impatient with vernacular to be implemented at the college” for liturgical celebrations, he said. “The difficulty was the Roman congregations hadn’t translated the prayers yet, hadn’t done anything. So you’ve school riots, you’ve got school protests at the North American.”

Once the student council at the NAC even called the Associated Press to state their complaint that an upcoming consistory of the College of Cardinals was “medieval” and “out of touch,” he said.

From faculty discussions about whether seminarians should be allowed to wear beards to student-led protests against the Vietnam War, the episodes Msgr. DiGiovanni recounts in the book often mirrored the political and cultural developments in society at large.

During the war years, “you had placards and you had threats of public protest at the Gregorian University,” he said. “They shut the university down a few times.”

In one student protest, in 1969, a group of seminarians changed one of the college’s traditional pilgrimages from “the seven basilicas in Rome to an anti-war protest,” he said.

The students, he said, even experimented with the boundaries of the priestly discipline of celibacy. “There was a thing called the ‘third way’ in the 1960s and 70s that said: You are a priest, you are a nun, you are a brother, and you vowed yourself to celibacy, where you can’t get married, you can’t have sex, but I can date,” he said.

“There was this bunch of guys at the college and they’re out dating,” he said. “The seminary had pretty much given up its authority, and so it begins a period, really, of chaos.”

When asked how his classmates, some of whom are now U.S. bishops, responded to the book, Msgr. DiGiovanni said he had received a lot of positive feedback. “We all went through the same thing, and no one would say that the North American College was unaffected by the American culture at the time.”

Many U.S. seminaries “during the 1970s, ’80s and early ’90s were like the movie ‘Animal House’ with daily Mass,” he said.

[hotblock2]

Both Msgr. DiGiovanni and the current rector, Father Harman, give credit to former rector Cardinal Edwin F. O’Brien for bringing order to the seminary in the early 1990s.

“If you let kids be kids, they are going to be kids,” Msgr. DiGiovanni said. “The church has something to offer them and some idea and program how to literally form, sculpt these individuals’ minds and hearts and souls to be more in tune with our Lord and with the church.”

Father Harman, the current rector, also emphasized that most Vatican documents on priestly formation since St. John Paul II have moved toward a more rigorous formation program.

Life at the NAC today is like “living in a fraternity, in the best possible use of that word — not a place that’s crazy or is sort of unhinged, but a place that is unified and joyful,” Father Harman said.

The NAC is “a house of brothers,” he said, with a diverse group of men “of one mind and one generous heart.”

PREVIOUS: Central African priests use Facebook to express outrage, appeal for help

NEXT: Vatican II liturgical reform ‘irreversible,’ pope says

Share this story