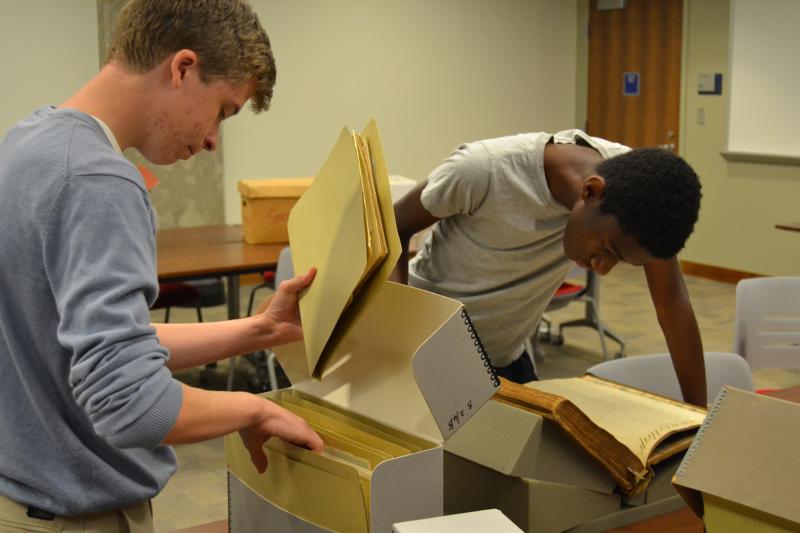

Gonzaga College High School students look through the archives in late June at Georgetown University in Washington. Gonzaga history teacher Ed Donnellan and six students searched through the archives to unearth any ties to slavery at the Jesuit-run high school. (CNS photo/courtesy Gonzaga College High School)

ARLINGTON, Va. (CNS) — After Georgetown University last year publicly acknowledged it had benefited from the sale of 272 enslaved women, men and children in the 1800s, a high school teacher at a Jesuit school in Washington invited the historian from the institution who had researched the sale to speak to students in his history classes.

Some students asked Adam Rothman, the historian and Georgetown professor, whether their school, Gonzaga College High School, also may have benefited from slavery. For a time, the Jesuits from Georgetown back then operated Washington Seminary, which later became Gonzaga.

The professor said he didn’t know but challenged students to find out, said Gonzaga history teacher Ed Donnellan, who invited Rothman to speak to his classes.

[hotblock]

Six students, along with Donnellan, took up the challenge and presented their findings to an audience Nov. 5 at the Ignatian Family Teach-in for Justice. The annual event, attended by approximately 2,000 students from Jesuit-run high schools and universities in the U.S., focuses on social justice issues.

The students were given access to a variety of records at Georgetown University’s archives, which had accounting books, written histories, enrollment records and other documents pertaining to what was then Washington Seminary.

Daniel Podratsky, a junior at Gonzaga, said he and the other students who volunteered were “very surprised” at what they found in the records.

“It’s an unfortunate history,” he said.

In the documents, they found references for what may have been two transactions, and perhaps others, related to slaves. One may have been for payment for transport of an enslaved person to a Jesuit-run plantation in Southern Maryland and the other documented a payment for “weeding in the garden” at the seminary to a person named Gabriel, listing no last name, possibly the slave of a seminary student.

There also are other transactions, clues that the students will further research to understand as much as they can about the school’s ties to slavery.

“We’re at the beginning of this,” said Donnellan, who also is looking at the possibility of taking students to visit the remnants of the Jesuit slave plantations in Maryland. Donnellan said the information, much like at Georgetown University, “sat there for years and no one talked about this.”

“I don’t think we as a country have faced this,” he said.

[tower]

The students spent two weeks at Georgetown during their summer break looking at records for about five hours each day, and they think there’s more waiting to be found.

Junior student Hameed Nelson said the experience taught him that “it shows what you can find, if you ask the right questions.”

The students said their findings were met with a variety of reactions from other students. Some said, “we need to do something about it,” said Joe Boland, who participated in the research with his brother Jack, as well students Jack Brown and Matthew Johnson.

Other students were grateful for the work they had done. Others said: “What does this have to do with me?”

In light of the students’ findings, Jesuit Father Stephen Planning, president of the school, issued a statement saying that “while more needs to be done to flesh out the details of Gonzaga’s past, it is clear that the Washington Seminary had connections to slavery in the earliest years of its existence. This is a fact about our past that we cannot deny, and it is one that we need to face with sincere humility.”

The priest commended the students and their teacher for the work, for which they received no school credit, but they said they didn’t need it.

“Why does it matter that that the Washington Seminary had connections to slavery nearly 190 years ago?” Father Planning asked. “Because in order to be true to who we are as a Gonzaga community, we need to stand before God not just celebrating our laurels and accomplishments, but acknowledging our sins and failings.

“Our past sinfulness matters, both as individuals and institutions,” he continued. “As much as we hate to admit it, our past sinfulness has an impact on who we are today. It is only when we accept our entire history, the good and the bad, that God’s mercy can move our hearts to greater humility, compassion and understanding.”

Donnellan, the history teacher, said the school also is looking at creating a working group, modeled after one formed at Georgetown, to see what, if any, amends the school can make. One might be to honor the slaves in a permanent way at their school, particularly Gabriel, whom they believe was later emancipated and consider “a Gonzaga brother,” Donnellan said.

PREVIOUS: Chicago-area Catholics, Lutherans renew covenant between their churches

NEXT: Federal court halts construction of Pa. pipeline on nuns’ land

Share this story