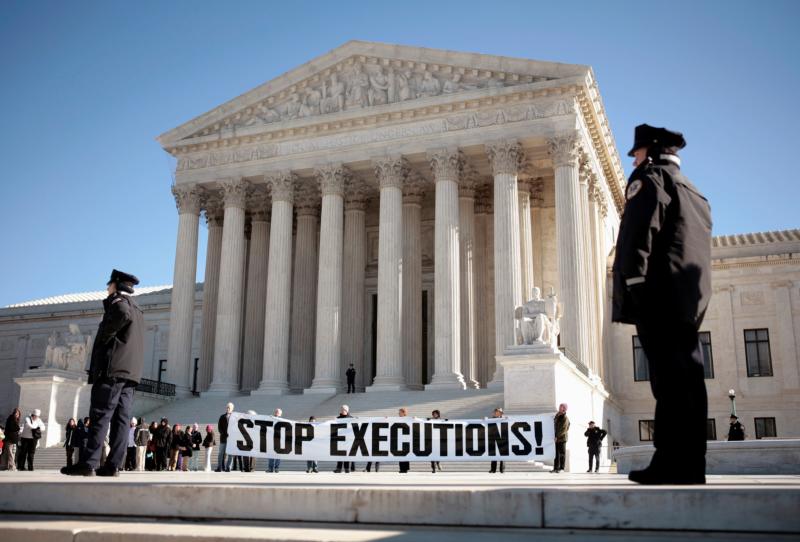

Protesters calling for an end to the death penalty unfurl a banner in late March outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington. (CNS photo/Jason Reed, Reuters)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — While much of the focus has been on the Supreme Court, state legislatures, governors and juries in the ongoing fight to abolish capital punishment in the United States, the head of the Death Penalty Information Center suggested that counties may be key.

It’s county prosecutors, most of them elected by voters, who decide whether to pursue a death sentence for murders and other crimes, said Robert Dunham, the center’s executive director.

“Riverside County (California), Clark County, Nevada, and Maricopa County in Arizona, imposed 12 (death) sentences, 31 percent of the entire national total,” Dunham said. “But for those three outlier counties, 2017 would have been the second consecutive low for death penalties in the United States.”

[hotblock]

Harris County, Texas, which includes America’s fourth-largest city, Houston, neither imposed a death sentence nor executed anyone this year for the first time since 1974. This made native Houstonian Karen Clifton, executive director of the Catholic Mobilizing Network, another anti-death penalty group, quite happy.

Clifton credited the change to a newly elected district attorney who has “found other means to handle the cases,” including sentences of life without parole. “Clifton said she and retired Archbishop Joseph A. Fiorenza of Galveston-Houston paid a visit to the new D.A. over Thanksgiving to see what support they could provide.

“And Philadelphia, which in 2013 ranked third in its death row (cases), imposing an average of one death sentence every other year, just elected a prosecutor who won’t use it,” Dunham told Catholic News Service.

These changes show the death penalty is “not driven by the severity of the crime, it’s driven by the arbitrary lottery of where a homicide occurs. And who the local prosecutor is,” he added.

“Even if the death penalty is imposed less and less, it is not being imposed in a more focused way against crimes that are the worst of the worst. The cases are still as arbitrary as they were in the past.”

The Catholic Mobilizing Network launched the National Catholic Pledge to End the Death Penalty. Clifton said it has garnered 15,000 signatures. Those who sign the pledge are then invited to join the network’s Mercy in Action campaign. “If they do that, they get a monthly email that tells them who’s going to be executed, and an action plan (to prevent the death sentence from being carried out): letters to the warden, to the board of parole, to the governor.

“We can metrically count 20 of the stays” to the interventions of pledge signers,” Clifton said — more than half the 39 stays granted in 2017. “It’s saving lives, it’s helping people, it’s calling attention that Catholics are against this.”

Pope Francis reiterated the church’s stance against capital punishment in October. “The death penalty is an inhumane measure that humiliates, in any way it is pursued, human dignity. It is, of itself, contrary to the Gospel because it is freely decided to suppress a human life that is always sacred,” he said.

[tower]

The pope spoke at a forum commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which itself was modified in 1999 to include stronger language against the death penalty. That year during a visit to St. Louis, St. John Paul II said modern society has the means of protecting itself without imposing the death penalty.

Nationwide, 39 death sentences were issued in 2017, the second lowest number since 1972, and 23 executions were carried out, up from 20 last year but still the second-lowest number since 1991, according to the Death Penalty Information Center’s 2017 report, issued Dec. 14.

Four people who had been on death row were exonerated, bringing the number to 160 since 1973. “The many exonerees, and realizing who we are executing, has helped put a face on the death penalty,” Clifton said in a Dec. 13 email to CNS.

“Juries are going for life (in prison) when given the option,” Clifton added. Florida changed its law to require a unanimous jury recommendation for the death penalty; previously, only a majority of the jury had to recommend a death sentence. Alabama lawmakers also repealed a bill that allowed for judges to override a jury’s life sentence and order capital punishment instead.

“As the drugs have resulted in so many botched executions, people are coming to realize there is just not a good way to kill people,” Clifton said. The Death Penalty Information Center’s report noted how Nevada and Nebraska this year permitted the use of the opioid prescription drug fentanyl to be used in executions.

“It’s certainly ironic that at the same time that states are saying that fentanyl is dangerous and unsafe and poses a significant public health hazard, that we’re seeing states arguing that it is safe and effective for use in executions,” Dunham said.

Regardless of the toll opioid abuse has taken in American society, “companies don’t their drugs used for executions,” Dunham added, “and as long as there is unified pharmaceutical opposition to their medicines use to kill prisoners, we will be in a situation where states are looking for drugs anywhere they can and come up with experimental drug cocktails to carry out executions.”

Episcopal appeals to spare the lives of condemned prisoners met with mixed success in 2017.

Saying “justice needs to be tamed by mercy,” Bishop Felipe J. Estevez of St. Augustine, Florida, and two Georgia bishops called Jan. 31 for Georgia to drop the death penalty in the case of Steven Murray, who was convicted accused of killing a priest.

“We have great respect for the legal system and we believe Murray deserves punishment for the brutal murder, but the sentence of death only perpetuates the cycle of violence,” the bishops said. In October, Murray’s sentence was commuted to life without parole.

Florida’s bishops appealed to Gov. Rick Scott to commute the sentence of condemned murder Mark Asay, but Asay was executed Aug. 25, one day after their appeal. Similarly, a plea from Virginia’s bishops to Gov. Terry McAuliffe was ignored as William Morva, 35, was put to death for the murder of a hospital security guard and a sheriff’s deputy, despite claims of the man’s severe mental illness.

After the January execution of Ricky Gray, who confessed to killing a family of four in 2006, the Virginia bishops condemned the execution, saying: “Knowing that the state can protect itself in ways other than through the death penalty, we have repeatedly asked that the practice be abandoned. Our broken world cries out for justice, not the additional violence or vengeance the death penalty will exact.”

PREVIOUS: Archbishop Gomez sees signs of God’s presence even in fiery destruction

NEXT: In #MeToo movement Catholic Church can play role in discussion, healing

Share this story