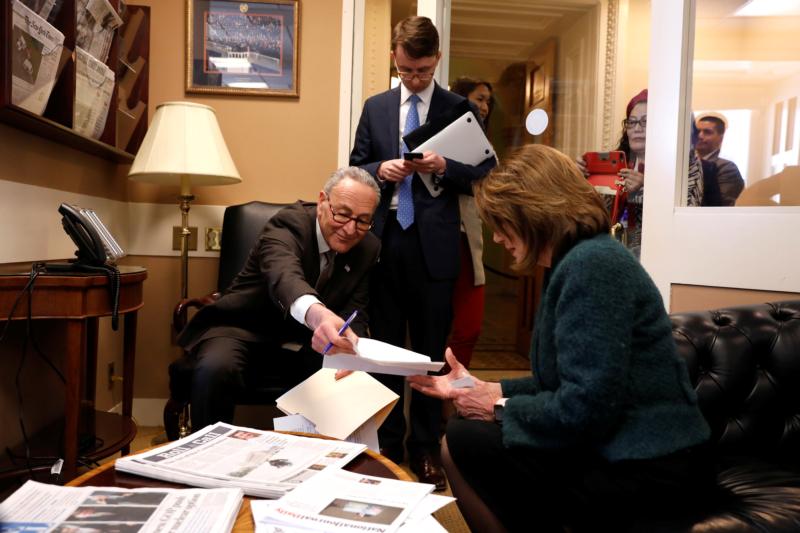

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., shares notes with House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., a Catholic, ahead of a news conference about the omnibus spending bill as it was moving through Congress on Capitol Hill March 22 in Washington. The Senate passed the bill March 23. (CNS photo/Aaron P. Bernstein, Reuters)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — The 2,000-page omnibus spending package passed by Congress in overnight sessions March 22 and signed into law the following day by President Donald Trump may not meet everybody’s definition of omnibus.

Some might argue that instead of “omnibus,” the proper word is “ominous.”

And if $1.3 trillion can’t solve everyone’s wish list, then what can?

[hotblock]

The original spending package was approved Feb. 9 to avert yet another government shutdown, yet despite all the money in that bill, the bill imposed another government funding deadline of March 23.

Some in Congress, mainly Republicans, who advocate for reducing the size of the federal government, dreaded the size of the spending measure. Many of those senators and representatives voted against it, but not enough to counteract those who voted for the bill.

Others in Congress, mostly Democrats, lamented that the bill had no provisions for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, the federal program for those brought into the United States without legal permission as minors by their parents. Some of those Democrats voted against the bill, but others voted for it, saying it was the best deal they could get as the minority party in Congress.

When a keep-the-government-open bill comes to the floor, it can become a magnet for provisions entirely unrelated to keeping the government open. A 2,000-page bill suggests that many, many such provisions survived the bill.

One such provision was the continuance of federal funding for Planned Parenthood, the nation’s single largest provider of abortions. Although none of the federal money pays directly for abortions, there had been talk over the past year of defunding Planned Parenthood due to some lawmakers’ vocal opposition to its role in abortion.

Another such provision was $50 million targeted for security at houses of worship and religiously based nonprofit organizations. In recent years, there had been a spate of violence at houses of worship, including the shooting deaths of 26 during services at First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas; the shooting deaths of nine at a Bible study at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015; and attacks at mosques in the Upper Midwest at a rate reported by CNN last year of nine a month.

The omnibus package contains $4.5 million for salaries and expenses for the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Commission chairman Daniel Mark told Catholic News Service in a March 29 telephone interview from Minneapolis that the funding had been expected. Previous allotments had been in the area of $3.5 million, he added.

[tower]

The money, Mark said, will be put to good use. The Frank Wolf International Religious Freedom Act, passed in December 2016, “added to our mandate to keep fuller lists, complete lists, of prisoners of conscience. We have an ongoing project of keeping lists of as many of them as we can,” he said. “We’ll need more staff, more outside contractor work. There’s a lot of time that goes into compiling the list and making sure the information is carefully verified.”

The commission was asked, in the 2016 bill, to identify “entities of particular concern” — stateless groups restricting religious liberty such as the Islamic State — in addition to “countries of particular concern,” which has long been in the commission’s portfolio. It also has been asked to help train Foreign Service officers on religious freedom issues. “We kind of have a consulting role with the State Department,” Mark said. That, and upgrading the commission’s website to meet federal Web benchmarks, will account for the extra spending, he told CNS.

The omnibus package also contains $10 million for religious freedom programs that, according to Mark, go through the State Department, which has its own office for religious freedom. “Former Secretary (of State Rex) Tillerson had proposed reorganizations that brought the Office of Religious and Global Affairs into that,” Mark said.

Another spending feature was $5 million to aid persecuted religious minorities in the Middle East and Africa. The issue of U.S. aid delivery in these areas has long been a thorn in the side of Christian leaders who believe the aid groups that typically receive funding from the U.S. government pay scant attention to the religions whose pull have kept people from fleeing terrorism hot spots en masse.

In a March 29 email to CNS, Thomas Farr, director of the Religious Freedom Research Project at the Berkley Center of Georgetown University in Washington, said he did not have details about the money — with the House being given 16 hours to ponder a 2,000-page bill, details about many initiatives remained sketchy — but had ideas “about how funds should be employed to reduce persecution.”

Even at 2,000 pages, some things can be noticeably absent.

One such absence that was “deeply disappointing” to the U.S. bishops was the Conscience Protection Act, which had no monetary impact. The provision is aimed at protecting individual physicians, nurses or other health care professionals who refuse, on moral grounds, to assist in abortions when asked to do so by their employers.

The provision would have taken the core policy of the Weldon Amendment, which has been part of the annual federal Health and Human Services appropriation since 2015, and written it into permanent law.

Those “inside and outside of Congress who worked to defeat” this legislation “have placed themselves squarely into the category of extremists who insist that all Americans must be forced to participate in the violent act of abortion,” said a March 22 joint statement by Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan of New York, chairman of the U.S. bishops’ Secretariat for Pro-Life Activities, and Archbishop Joseph E. Kurtz of Louisville, Kentucky, chairman of the bishops’ Committee for Religious Liberty.

PREVIOUS: Panel on faith, faithful in politics called needed in ‘polarized world’

NEXT: Helping kids, families stay safe on Snapchat

Share this story