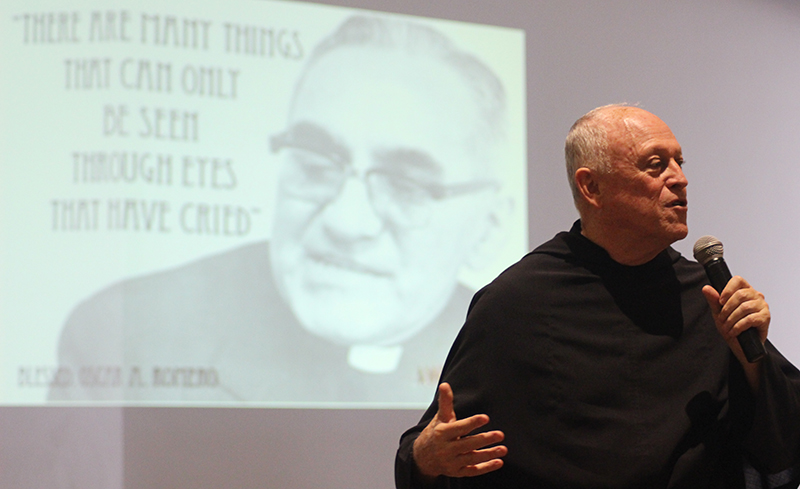

Father Arthur Purcaro, O.S.A., speaks on the significance of St. Oscar Romero at an Oct. 9 lecture hosted by La Salle University. Romero, archbishop of San Salvador, was martyred in 1980 and canonized on Oct. 14. (Photo by Gina Christian)

The recent canonization of Oscar Romero is a call for Catholics to truly become the people of God, according to Augustinian Father Arthur Purcaro.

Romero, the archbishop of San Salvador, was assassinated in 1980 while celebrating Mass in a hospital chapel. His outspoken defense of El Salvador’s poor and marginalized, and his plea for peaceful solutions to that nation’s extensive social and political conflicts, had put him at odds with both a repressive regime and leftist guerrillas. A 1993 United Nations report determined that Major Roberto D’Aubuisson, a far-right leader in El Salvador, had ordered Romero’s assassination.

Pope Francis declared Oscar Romero a saint Oct. 14 in Rome, along with St. Paul VI.

At an Oct. 9 lecture in the chapel of La Salle University in Philadelphia, Father Purcaro – who has spent over four decades working in Peru – stressed that Romero’s legacy, which transcends political disputes, is more relevant than ever.

[hotblock]

“The only reason Oscar Romero would put up with a celebration such as his canonization is so that we can realize our role as Catholics,” said Father Purcaro, now an adjunct professor and acting vice president for mission and ministry at Villanova University.

The evening’s presentation, entitled “Hear the Cry of the Poor: St. Oscar Romero,” was organized by Franciscan Father Frank Berna, director of La Salle’s graduate religion program in theology and ministry. Father Berna noted that the canonization was “a long time coming” and deserved to be marked not just at the Vatican, but locally.

“Romero really moved from being a theologian of book and traditional creed to a theologian of the people and their experience,” said Father Berna, referring to Romero’s increased identification with El Salvador’s landless poor throughout his ministry.

Romero’s cause for canonization was seen by some as problematic due to his association with liberation theology, a Catholic movement that emerged in Latin America after the second Latin American Bishops’ Conference, held in Medellín, Colombia in 1968.

Liberation theology stressed the church’s preferential option for the poor and the role of industrialized nations in promoting systemic economic injustice. Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez authored the movement’s key overview, “Teología de la liberación,” in 1971. Critics claimed the movement served the interests of Marxism rather than the Gospel.

[tower]

During his talk, Father Purcaro – who has met and worked with Father Gutiérrez – outlined the basic principles of liberation theology, asking audience members to decide for themselves if Romero was part of the movement.

An awareness that God reveals himself in human history is central to liberation theology, said Father Purcaro.

“We don’t bring God to others,” he said. “We go to discover God. He is here, now.”

Father Purcaro also observed that there are different types of poverty, not all of which are redemptive.

Material poverty, usually the result of greed and selfishness, is not part of God’s plan for humanity, he said. Christ’s declaration that “the poor you will always have with you” (Matthew 26:11) has often been used as a justification for neglecting the church’s role in promoting social justice.

Spiritual poverty, in contrast, enables one to admit utter dependence on God, while voluntary poverty leads to solidarity with others.

By seeing ourselves in relation to each other, we can recognize that “God didn’t choose to save us individually but as a people, together,” said Father Purcaro.

The current clerical sex abuse crisis has highlighted the need to reclaim this sense of community, he added.

“We love to give the responsibility for the church’s holiness to the clerics,” Father Purcaro said. “We’ve allowed clericalism to be a replacement for being the people of God.”

Throughout the talk, Father Purcaro invited the audience’s approximately 60 members to pause for brief discussions with each other.

Savannah Sanchez, a senior in La Salle’s nursing program, found inspiration in Romero’s words displayed on a screen throughout the lecture.

“A lot of his quotes were very deep, and very easy to relate to, especially for someone who hasn’t studied much religion or theology,” she said.

Psychology major Elena Deligatti, also a senior at La Salle, agreed. Having been educated in Catholic schools since kindergarten, she knew of Romero, but developed a new appreciation for his significance after the Oct. 9 lecture.

“I think that a lot of the things that we learned about tonight apply to our generation,” Deligatti said.

That relevance is exactly what the lecture was designed to convey, said Father Purcaro, adding that Romero’s canonization was not an occasion for glorifying a single individual.

“We don’t need another hero, stained glass window or statue. We need to be the people of God,” Father Purcaro said. “If you need another statue in church, let it be a two-foot high ear, and be people who listen to one another from their hearts.”

***

Jhoselyn Martinez contributed to this story and provided English translations of interviews conducted in Spanish.

Related articles

Local reaction to the canonization of St. Oscar Romero:

Latino Catholics in Phila. inspired by Romero film, canonization

Salvadoran native lives out St. Romero’s legacy of justice

World news:

El Salvador celebrates its first saint, whose legacy continues

St. Romero’s brothers rejoice at his canonization

Young Salvadorans embrace St. Romero

Salvadoran archbishop asks pope to make Romero ‘doctor of the church’

PREVIOUS: Salvadoran native lives out St. Romero’s legacy of justice

NEXT: Latino Catholics in Phila. inspired by Romero film, canonization

Share this story