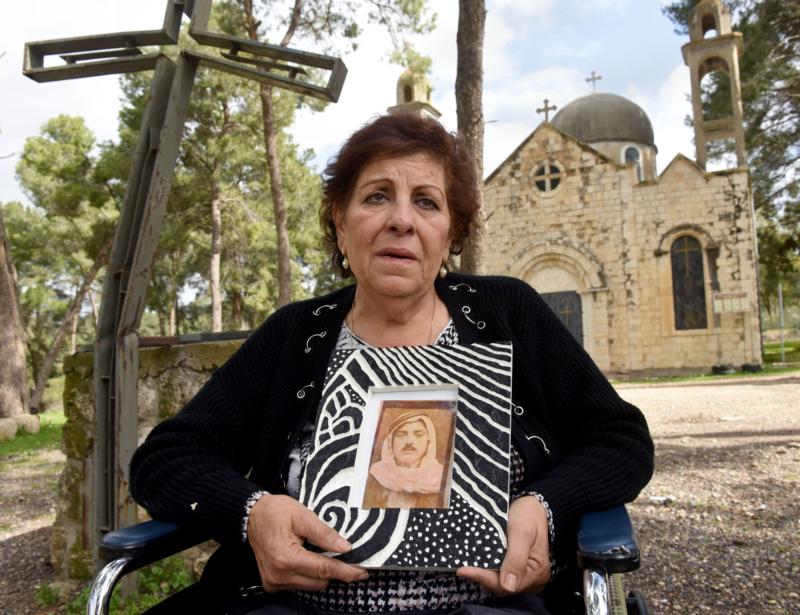

Salwa Salem Copty, 70, holds a photo of her father, Fares, in front of the Melkite Catholic Church of St. Jacob in Ma’alul village, Israel. Salwa, who now lives in Cana, is fighting for the right to visit her father’s grave in the Ma’alul cemetery, which is now enclosed in an Israeli army base. (CNS photo/CNS photo/Debbie Hill)

MA’ALUL VILLAGE REMAINS, Israel (CNS) — The destroyed Arab village of Ma’alul, located just outside of Nazareth, does not appear on any Israeli map, but it is etched on Salwa Salem Copty’s heart.

Copty’s widowed mother and her three older siblings, along with other residents, were expelled from the village in July 1948 during Israel’s War of Independence. Copty was born 16 days later.

Copty laments that she has no memories of Ma’alul, but she clings to the stories her relatives have told her about what life was like there. Now, at age 70, she still visits the site of the village, drinking coffee and eating pastries with her children and grandchildren in the shadow of the reconstructed Melkite Catholic Church of St. Jacob.

[hotblock]

But she is unable to visit her father’s grave because an Israeli air force base was constructed around the Christian cemetery shortly after the residents’ expulsion, and they have never been permitted to enter the base to go to the cemetery. Her father was killed a few months prior to the expulsion by a Jewish militia bullet and is buried in the cemetery.

“They told me father was in heaven and I would look at his picture and would see a cloud in the sky that looked like the picture, and I would think that my father is looking at me and is speaking to me, and I would talk to him,” said Copty, a retired social worker. She has enlarged the photograph of her father and keeps it in her home, still confiding her deepest worries and concerns to it.

“I am appealing to all sense of humanity for this request to visit the grave. I want to whisper on his grave, as if he will hear that he has a daughter named Salwa who misses him, just to touch the grave, the dust, his soul, the place where he walked, even where maybe he stepped. That drives me crazy,” she said.

Since 2000, Copty repeatedly has made formal requests to gain access to the cemetery to visit her family members buried there, but her appeals to various Israeli authorities through multiple channels have gone unhandled.

[tower]

“I dream about this grave. I’m begging. I just want to visit my father’s grave before I die and it’s too late,” Copty said. “You can’t just erase someone’s memory.”

On Jan. 13, Adalah, The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, filed a petition to the Israeli Supreme Court on behalf of Copty and her 93-year-old uncle, Subhi Mansour, to allow them to visit the cemetery. Mansour is the only living displaced resident of the village who can identify the location of the grave of Copty’s father, Fares Salem.

The petition, which will be heard by the court June 24, was filed against the Israeli defense and interior ministries and the Israel Land Authority and demands that Copty and Mansour be permitted to visit the cemetery. The petition also seeks clarification regarding why the Interior Ministry and ILA have not been required to preserve Ma’alul’s Christian cemetery and protect it from desecration or, alternatively, why it is not allowing the petitioners or anyone on their behalf to maintain and protect the cemetery from desecration.

“The desecration of and failure to maintain the cemetery, and the failure of Israeli authorities to respond to Copty’s appeals within an appropriate and humane time frame, are all violations of the constitutional right to dignity — both of the living and of the deceased — and a violation of her right to grieve at the family grave,” Adalah said in the petition.

This is the first time a case relating to access to a cemetery located inside a military base has been brought to court.

The government ministries did not reply to requests for a response from Catholic News Service.

Mansour told CNS: “We haven’t been able to visit the cemetery since 1948. … It’s not just us, everyone has family buried in the cemetery. Everyone should be able to visit their dead, place flowers on their graves.”

Copty’s oldest daughter, Odna — which means “return” in Arabic — accompanies her mother on visits.

[hotblock2]

“Because I have this name, I feel this village is always with me,” she said. “I always live my mother’s pain and suffering. Sometimes I wake up at night and she is crying to the picture.”

Along with the other descendants of the expelled families, Copty and her family return to St. Jacob Church, which they restored, on the second day of Easter for Mass, and her children attended the yearly summer camps held at the site to remember their village.

Today the remains of the destroyed village are overgrown, and the overturned rocks peek out from under rolling mounds of green grass, which has sprouted after a rainy winter, but Mansour can still point out where he lived and where Copty’s parents lived. He identifies one of the village’s wells amid the jumbled rocks.

Together with another niece who is an engineer, Mansour recently mapped out the pre-1948 village and, next to the church, they placed a large sign of the area marked with every family’s home. They also placed name markers next to every pile of rubble to identify the homes on the ground, but someone tore down all the name signs.

PREVIOUS: Australian church wraps first phase of historic lay council

NEXT: Pope amends canon law on religious who abandon their community

Share this story