WASHINGTON (CNS) — Dorothy Day’s need to connect with others and keep neglected people front and center would fit perfectly in the COVID-19 era.

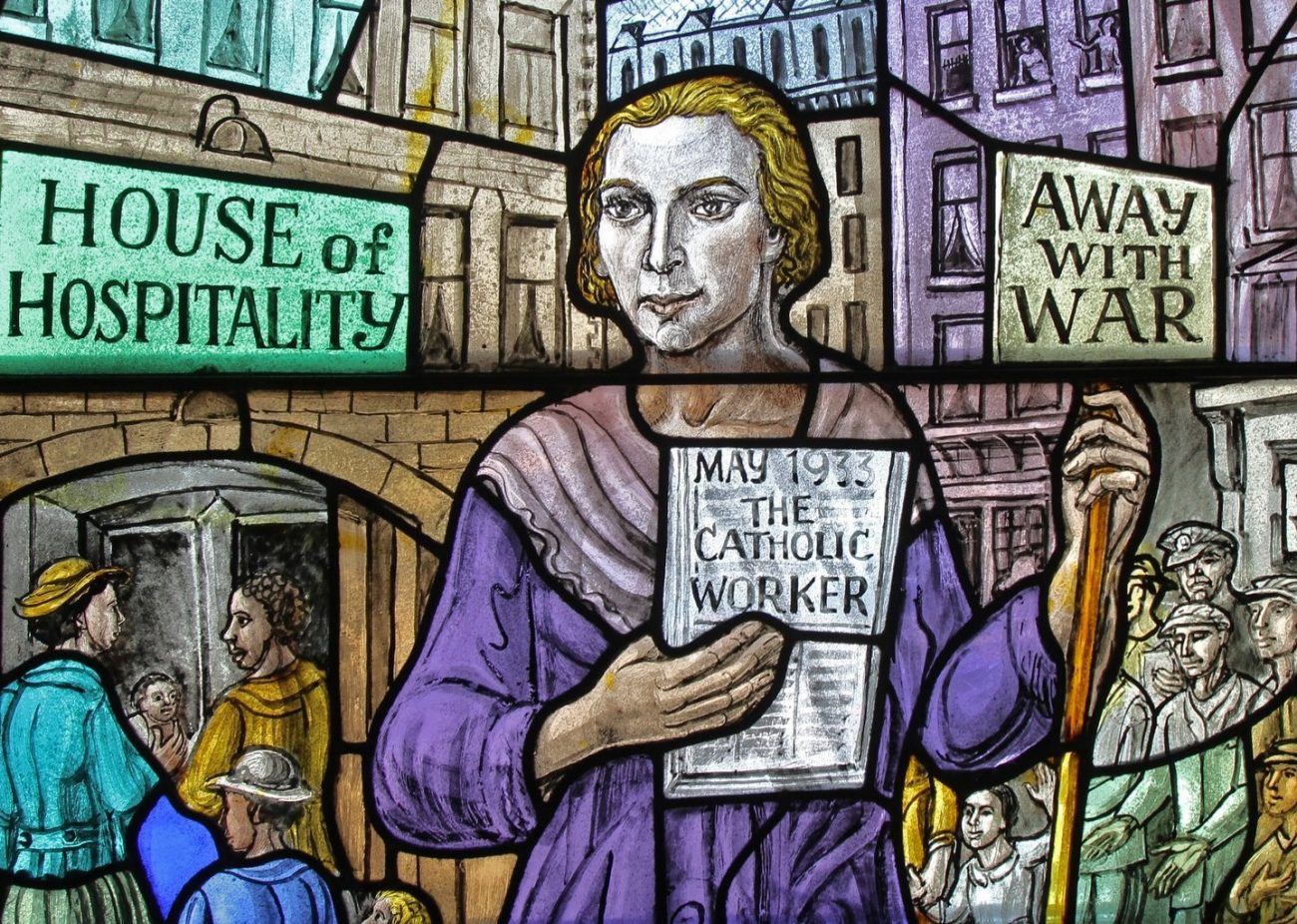

The 40th anniversary of the death of Day, the Chicago-based journalist, social-justice activist and co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, was the occasion of some online reflections on her life and career during a Nov. 29 webinar, which drew more than 2,000 registrants and was sponsored by the Dorothy Day Guild.

“The struggle to contain her anger was her crucible of holiness,” said Robert Ellsberg, editor of several volumes of Day’s writings.

[hotblock]

She liked to quote St. John of the Cross: “Where there is no love, put love, and you will draw out love,” but her skepticism about Social Security and for paying income taxes for government actions she considered immoral often drew her into irascibility with whatever authority figure crossed her path.

Day once, Ellsberg recalled, tried to simplify a dispute with Internal Revenue Agents by telling them, “Why don’t you tell me what I owe, then I’ll refuse to pay it?”

In her presence, you’d believe “it would be a great adventure and tremendous fun to be a better person,” Ellsberg added. “She did not believe that what she did was out of the reach or ordinary people.”

“Revisiting her work … I was struck by the sense that Dorothy Day is the patron saint of mid-life,” said Paul Elie, author of a joint biography of Day, Walter Percy, Flannery O’Connor and Father Thomas Merton, “The Life You Save May Be Your Own.”

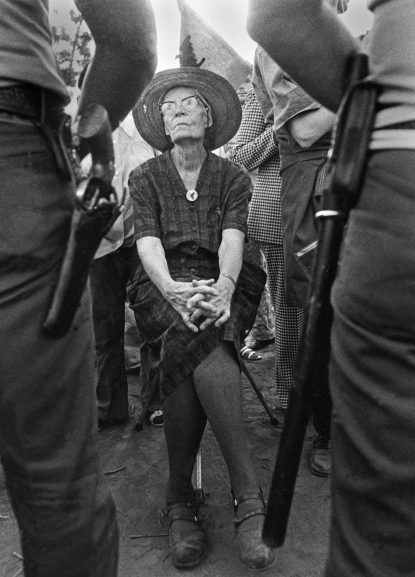

This is a still from the “Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story,” a film by Martin Doblmeier, showing Day in her later years being confronted by police during a protest. (CNS photo/courtesy Journey Films)

Day visited Cuba to meet Fidel Castro, went to Rome to fast, to India to meet St. Teresa of Kolkata, and to California to encourage Cesar Chavez, founder of the United Farmer Workers. “All this happened after she was 55, and that’s incredibly emboldening if you’re 55 or older,” Elie said.

Day, born in 1897, experienced her greatest fame as a pacifist and organizer beginning in the 1950s. A grassroots effort for Day’s canonization was initiated in 1983.

Cardinal John J. O’Connor of New York formally opened her cause in 2000, which received Vatican approval, giving Day the title “Servant of God.” The Dorothy Day Guild was established to propagate her life and works. In 2012, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops endorsed the cause.

A documentary film in support of the cause, “Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story,” was released earlier this year.

Reading Day’s diaries, “I sometimes wonder whether Dorothy suffered too much,” said David Brooks, a New York Times columnist, who has written about Day on occasion.

“People don’t come out of that kind of suffering with empty hands. She came out of that with full hands.”

Still, “you feel bad for all she put herself through,” Brooks observed.

As a front-line worker during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19, “there’s no question that it had a deep effect on her,” Elie said. Today with the terrible isolation of COVID-19 quarantines, “We’re thinking the pandemic will change us. That’s not how things work.”

“Let’s hope there’s a Dorothy Day out there” who will learn the sacrifice of discipline while motivating others, he said.

In March and April, with the pandemic in its earliest stage, there was a “sense that neighbors were getting to know each other” and this would be hopeful sign for knitting communities together, Brooks said. However, “there’s plenty of evidence that this has been terrible for Americans. We are a more fractured society than we have ever been.”

Anne Snyder, editor-in-chief of Comment magazine and also Brooks’ wife, praised Day for her “integration of the craft of writing and choices of sacrifice, as well as “a desire to not succumb to the categories of the world.”

Elie thought Day’s example could help people with “the problems of human society that abide — the pandemic, urban life vs. rural life, the church forming alliances with autocrats. … We have to find our own era’s solutions to those problems.”

“I think the social commitments we’re seeing in this moment are beautiful,” Elie continued. With the pandemic taking a brutal toll on in-person commerce and that simple form of personal interactions, “into that space pour people calling out for justice. To see people stepping up to vote for the first time, it’s a beautiful thing.”

***

More information about Dorothy Day’s sainthood cause can be found on the website of the Dorothy Day Guild, http://dorothydayguild.org.

PREVIOUS: Detroit ‘families of parishes’ plan moves ahead; Pittsburgh announces mergers

NEXT: ‘Let my people worship,’ archbishop says after California church decision

Share this story