OXFORD, England (CNS) — Polish Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski, scheduled to be beatified Sept. 12, was ready to seek agreements in a Christian spirit, but also firmly believed “certain boundaries could not be crossed,” said a leading theologian and political scientist.

Father Piotr Mazurkiewicz, former secretary-general of the Brussels-based Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Union, COMECE, told Catholic News Service April 27 the beatification would remind Catholics everywhere of the church’s challenges under communist rule in Eastern Europe.

[hotblock]

“In an age when it’s generally assumed any leadership role requires a compromise of conscience, he showed, like the English St. Thomas More, this wasn’t so,” the theologian said.

Beatification is a step toward sainthood, and Poland’s Catholic information agency, KAI, said 37 volumes on the cardinal’s sanctity had been amassed during his 1989-2001 diocesan process for canonization.

In October 2019, the Vatican Congregation for Saints’ Causes said the inexplicable recovery of a dying 19-year-old cancer patient from the Szczecin-Kamien Archdiocese in 1988 had been confirmed as a miracle attributed to Cardinal Wyszynski’s intercession. His beatification, originally scheduled for 2020, was postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mother Elisabeth Rosa Czacka, who founded the Franciscan Sister Servants of the Cross in 1918 and a pioneering center for blind children, will be beatified alongside Cardinal Wyszynski. She died in Poland in 1961.

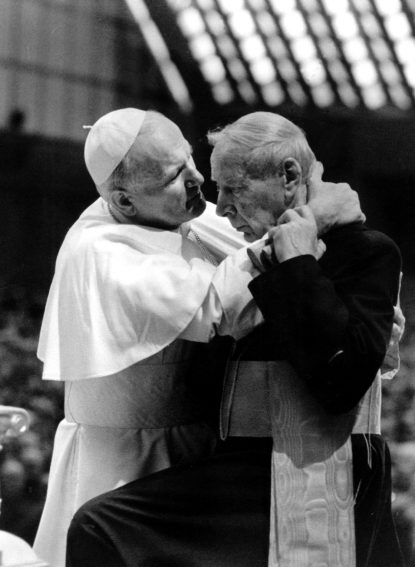

St. John Paul II and Polish Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski embrace at the Vatican in this 1978 photo. Cardinal Wyszynski is scheduled to be beatified in Warsaw Sept. 12, 2021. (CNS photo/Arturo Mari)

The late Catholic historian Andrzej Micewski told Catholic News Service in 2001 that Cardinal Wyszynski’s leadership had resulted in a victory that was not only political, but also had taught important lessons about securing church freedoms under hostile conditions.

“Wyszynski criticized the communist state, but also compelled communist rulers to deal with him, in this way ensuring his church became Eastern Europe’s strongest,” Micewski said.

Born in Zuzela, Poland, Aug. 3, 1901, Stefan Wyszynski was ordained at Wloclawek in 1924, later serving as a chaplain to Poland’s underground home army under wartime German occupation.

Pope Pius XII named him bishop of Lublin in 1946 and archbishop of Warsaw-Gniezno two years later. In 1950, despite Vatican misgivings, then-Archbishop Wyszynski signed the first church accord with a communist government, which promised the church institutional protection in return for encouraging “respect for state authorities.”

The deal was swiftly violated by the communist side, and Cardinal Wyszynski was arrested with hundreds of priests in September 1953. He was held until October 1956, when a new communist leader, Wladyslaw Gomulka, sought his help in calming industrial unrest.

“When he was arrested, he didn’t know what awaited him — although it turned out to be three years’ detention, it could just as easily have been a show trial and death sentence,” Father Mazurkiewicz told CNS.

“When we read his detailed notes today, it’s striking how the communist rulers also treated Cardinal Wyszynski as an authority and felt morally inferior beside him, as they tried to present their own perspectives and interests,” he said.

Having reached a new deal with Gomulka to allow freer church appointments, some religious teaching and 10 Catholic seats in Poland’s State Assembly, Cardinal Wyszynski headed the Archdiocese of Warsaw-Gniezno until his death May 28, 1981.

Among his proteges was the future St. John Paul II. When then-Father Karol Wojtyla was appointed auxiliary bishop of Krakow in 1958, the cardinal presented him to a group of priests, saying “Habemus papam” (“We have a pope”).

Father Mazurkiewicz told CNS Cardinal Wyszynski’s beatification would be a “form of penance” against recent church scandals by recalling “good and saintly aspects” of Christian life. He also said the cardinal’s role in rebuilding ties Polish with Germany, through a reconciliatory letter to German bishops during the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, had been important for post-war Europe.

PREVIOUS: ‘Patients are … dying in front of my eyes,’ says India hospital director

NEXT: Pope calls for monthlong global prayer marathon for end of pandemic

Share this story