(Luisella Planeta Leoni/Pixabay)

An urgent call to address mental health issues among youth shows there’s plenty of reason for concern – and for hope, say archdiocesan experts and Catholic school educators.

Earlier this month, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy issued an advisory to highlight “real and widespread” mental health challenges in children, adolescents and adults, noting that depression, anxiety, behavioral issues and suicide have risen significantly in recent years. From 2007 to 2018 alone, the nation saw a 57% increase in suicide rates among youth ages 10 to 24.

The COVID pandemic has only exacerbated these trends, said the advisory. Lack of socialization, illness and death among family members, loss of household income and insufficient access to supportive services have all taken a toll on the nation’s youth.

[hotblock]

Last year, mental health visits to the emergency room rose 31% among teens aged 12-17; in a one-month period earlier this year, hospital visits for suspected suicide attempts soared almost 51% among girls in that same age bracket.

The crisis demands a “whole of society effort,” said Murthy – and that’s exactly what human services and educational professionals in the Philadelphia Archdiocese are working toward.

‘Meeting children where they are’

The first step is “meeting the children where they are,” said Bryan Carter, president and CEO of the Gesu School, an independent Catholic school in North Philadelphia.

Last month, the school dedicated its annual symposium to discussing ways of managing pandemic stress in educational communities. A key part of that task is “(adjusting) expectations of where children should be academically,” said Carter in an email interview with CatholicPhilly.com.

[hotblock2]

“Obviously delivering instruction virtually was not ideal,” he wrote. “There may have been components of the curriculum that were not fully covered last year. … In modifying the curriculum, you allow for ‘catch up’ and reduce the stress on the students.”

Understanding the pandemic’s impact on kids’ “lives outside of school” is also essential, said Carter.

“Did a parent lose a job, thereby creating a financial hardship for the family? Did a family member contract COVID, or was a family member lost due to COVID?” he said. “We always ask ourselves what happened to cause the student to behave in a certain manner.”

Such trauma-informed care – which decodes the core reasons why youth engage in harmful behavior – also infuses the work of archdiocesan Catholic Social Services (CSS) and its numerous outreaches.

The agency’s wide array of resources includes five regional family service centers that serve as a first point of contact with CSS, providing parental education, benefits guidance and emergency assistance with food, clothing and shelter – all critical factors in mental health.

In collaboration with the Office for Catholic Education, CSS has embedded social workers at five archdiocesan high schools: Little Flower High School for Girls, Father Judge High School for Boys, West Catholic Preparatory High School, Neumann-Goretti Catholic High School and Monsignor Bonner and Archbishop Prendergast High School.

‘Every kind of trauma’

CSS has particularly long and deep experience with youth who have sustained “every kind of trauma, family discord and substance abuse,” said James Amato, secretary for archdiocesan Catholic Human Services.

Bette Kennedy, director of the archdiocesan Catholic Social Services program “A Better Way,” teaches youth impacted by trauma and violence to free themselves from destructive choices. (Bette Kennedy)

For the past two decades, CSS has operated “A Better Way,” which teaches social responsibility and conflict management skills to youth ages 12 to 18 involved in the juvenile justice system. Currently funded by a partnership the Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services (DHS), the program’s court-mandated sessions enable teens to free themselves from destructive mindsets and behaviors, said program director Bette Kennedy.

Through a partnership with Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services, CSS operates the St. Francis-St. Vincent Homes in Bensalem, which feature residential and educational programs, case management and both in-patient and outpatient clinical services for dependent and delinquent youth.

“We have a longstanding license with Pennsylvania for our mental health clinic at St. Francis-St. Vincent,” said Amato, adding the ministry’s psychiatric evaluations, crisis interventions and individual, group and family therapy sessions are vital to clients.

CSS also extends mental health services – in both English and Spanish — to unaccompanied migrant children in its transitional foster care program, working with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Migration and Refugee Services.

Licensed clinical psychologist Dr. James Black, who oversees CSS’s youth services division, said that for the kids he and his team serve, COVID has been “just another overlay” in their “difficult, impoverished lives.”

“It’s a cruel, harsh world to begin with for so many of them,” he said.

At the same time, said Black, youth “who struggle with connection and attachment” have been especially impacted by COVID restrictions.

Listening to kids

Amid turmoil in the home and in society, children need “consistency and perspective,” said Black.

“Kids want to belong somewhere,” said Kennedy. “Our youngsters are hurting. They’re dealing with so much, and some of them are just fending for themselves in homes where the parents themselves are in survival mode.”

Yet “each of these kids have a story,” although “they’re not being heard,” said Kennedy.

“Teenagers are willing talk,” she said. “Will they disclose a lot? No, but once they actually trust you, they do talk.”

Parish ministries can play a crucial role in getting youth to open up, said Marisally Santiago, director of the archdiocesan Office of Ministry with Youth.

“Make sure youth know they are seen,” she said. “Welcome them, engage them when you see them. Ask them about their day, their life.”

Like Black, Santiago stressed the importance of creating environments of “safety and consistency.”

“Youth take on what is in their immediate surroundings, the joys and troubles of family and friends,” she said. “Allow them a safe place where they can build trust to be themselves and share with those they know care.”

A field hospital of faith

Bringing the issue of mental health out of the shadows and into open discussion paves the way to healing, said Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Kathleen Schipani, director of the archdiocesan Office for Persons with Disabilities and the Deaf Apostolate.

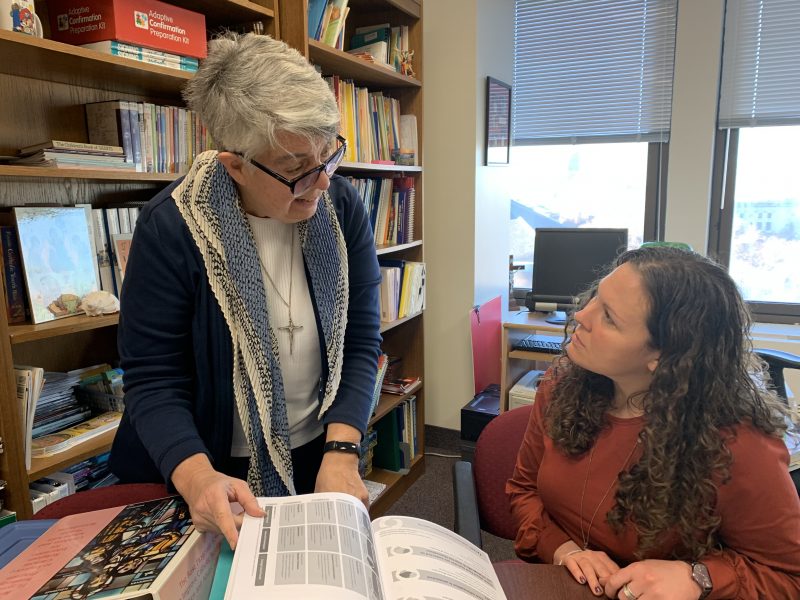

Mental health ministries within the church are helping to lessen the stigma of mental illness, said Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Kathleen Schipani of the archdiocesan Office for Persons with Disabilities and the Deaf Apostolate, seen here with Dr. Danielle Heeney, director of the archdiocesan schools of special education. (Gina Christian)

“I think mental illness can be a hidden disability and a hidden concern, and it also brings with it – sad to say – a stigma,” she said. “People don’t feel free to talk about it the way they would if it were a diagnosis of cancer.”

However, she added, that silence is steadily being broken, and the Catholic Church is “doing many things to support people who have mental illness.”

She pointed to the National Catholic Partnership on Disability and its council on mental illness, along with the Association of Catholic Mental Health Ministers, as leading voices within the church on the issue.

Through its faith and works of mercy, the church can chart a path to healing for those experiencing mental illness, said Black.

“Pope Francis talks about the church as a field hospital, and so I think we’re a part of that mission,” he said. “People are in pain, and it’s our job to ease that suffering. It’s the Gospel.”

Amato agreed.

“Where there’s faith, there’s hope that things can change and be different,” he said.

PREVIOUS: Guadalupe Mass shows Mary ‘etched’ into hearts of faithful, says archbishop

NEXT: Retired priest’s owl collection leads to children’s book series

Share this story