WASHINGTON (CNS) — As Oregon scientists announced May 15 that they had successfully converted human skin cells into embryonic stem cells, the chairman of the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Pro-Life Activities warned that the technique is morally troubling on many levels.

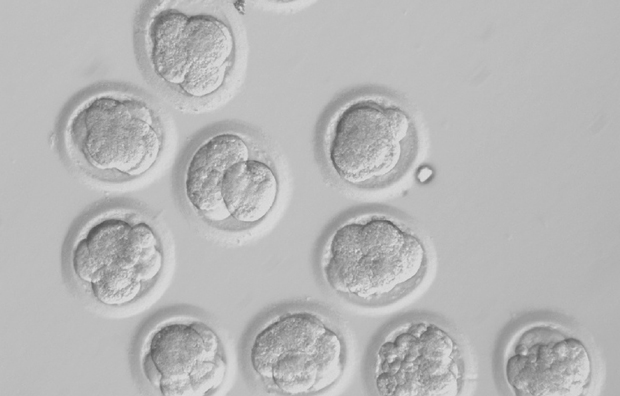

Scientists at the Oregon Health & Science University and the Oregon National Primate Research Center announced that they had successfully reprogrammed human skin cells to become embryonic stem cells, which are capable of transforming into other types of cells that could replace those damaged by illness or injury.

[hotblock]

Many news reports on the announcement referred to the research as human cloning, but the university’s release and a full report on the work in Cell magazine carefully avoided the term, except to say taking the work in the direction of reproductive cloning is unlikely.

The Oregon research team developed the unfertilized embryonic cells to seven days’ growth in a lab. Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley of Boston, who chairs the bishops’ committee, said the process created and destroyed more than 120 human embryos, which the church considers human life that must be protected.

“Creating new human lives in the laboratory solely to destroy them is an abuse denounced even by many who do not share the Catholic Church’s convictions on human life,” said Cardinal O’Malley’s statement. He also decried the conditions to which the women who volunteered for the experiment were subjected to increase the number of eggs they produced, saying it “put their health and fertility at risk.”

The researchers said their goal is to produce genetically matched stem cells for research and possible therapies, but Cardinal O’Malley said the same goals can be achieved “by scientific advances that do not pose these grave moral wrongs.”

Research using adult stem cells, or those derived after someone is born, as opposed to cells from embryos, has provided promising possibilities for treating some illnesses or injuries. The reprogrammed stem cells can be used to replace damaged cells.

A statement from the university said the process announced May 15 “is a variation of a commonly used method called somatic cell nuclear transfer. … It involves transplanting the nucleus of one cell, containing an individual’s DNA, into an egg cell that has had its genetic material removed. The unfertilized egg cell then develops and eventually produces stem cells.”

Although the university’s explanation of the breakthrough noted that the research “does not involve the use of fertilized embryos, a topic that has been the source of a significant ethical debate,” that doesn’t address the Catholic Church’s moral objections.

Richard Doerflinger, associate director of the U.S. bishops’ Secretariat for Pro-Life Activities, told Catholic News Service that as soon as human cells begin to divide into an embryo they are considered human life and that the destruction of such embryos is immoral.

The university release called it an “important distinction” that “while the method might be considered a technique for cloning stem cells, commonly called therapeutic cloning, the same method would not likely be successful in producing human clones otherwise known as reproductive cloning.”

The university said that several years of studies using monkeys “have never successfully produced monkey clones. It is expected that this is also the case with humans. Furthermore, the comparative fragility of human cells as noted during this study is a significant factor that would likely prevent the development of clones.”

“Our research is directed toward generating stem cells for use in future treatments to combat disease,” said the statement, quoting lead researcher Shoukhrat Mitalipov. “While nuclear transfer breakthroughs often lead to a public discussion about the ethics of human cloning, this is not our focus, nor do we believe our findings might be used by others to advance the possibility of human reproductive cloning.”

Doerflinger and Cardinal O’Malley said that no matter what the Oregon researchers intend to do with their studies, the techniques they have perfected might lead others to pursue human cloning that produces babies.

Cardinal O’Malley said: “This means of making embryos for research will be taken up by those who want to produce cloned children as ‘copies’ of other people. Whether used for one purpose or the other, human cloning treats human beings as products, manufactured to order to suit other people’s wishes.

“It is inconsistent with our moral responsibility to treat each member of the human family as a unique gift of God, as a person with his or her own inherent dignity. A technical advance in human cloning is not progress for humanity but its opposite.”

Doerflinger said that after controversy arose in the 1990s about the morality of seemingly promising research using embryonic stem cells — which led to congressional hearings and bans on using federal funding for all but a select few embryonic stem-cell lines — most such research has turned to using adult stem cells. Such cells hold the advantage of reducing the chances of rejection, because therapies are made from stem cells created from the person who will receive the treatment.

However, Doerflinger said, there are some researchers who have said they want to create human clones, whether to “hasten the next step in human evolution,” or simply to press the boundaries of scientific possibilities.

Whether the Oregon research leads to full human cloning attempts or is limited to cloning only as far as the embryo stage, Doerflinger said the bottom line ethically and morally is that “it’s never OK to create life only to destroy it. And it’s not only the Catholic Church that says that.”

PREVIOUS: Women religious uniting in nationwide effort to end human trafficking

NEXT: Helen Alvare blasts ‘sexual expressionism,’ government interference

Share this story