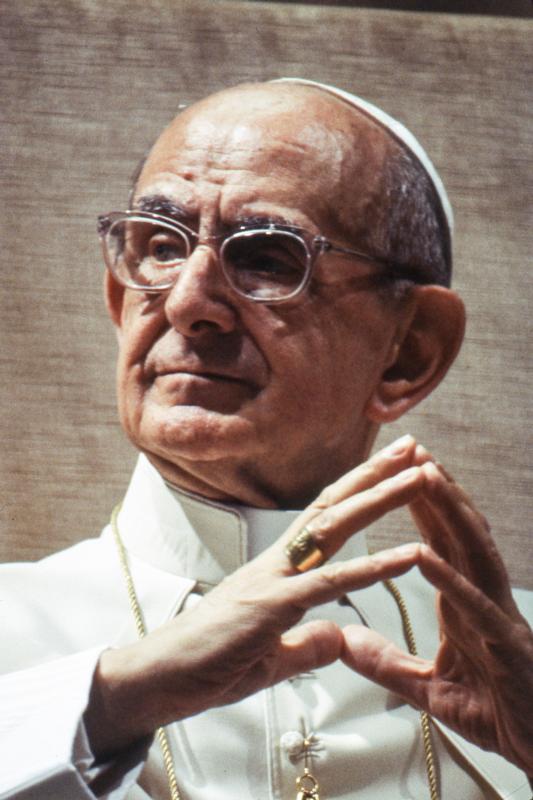

Blessed Paul VI is pictured in this undated photo.(CNS photo/Giancarlo Giuliani, Catholic Press Photo)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — These days when Pope Francis talks about integral human development and his vision of a church that goes to the margins of the world, he undoubtedly thanks a predecessor of 50 years ago for the inspiration.

Blessed Paul VI addressed “the progressive development of peoples” as “an object of deep interest and concern to the church” in his encyclical “Populorum Progressio” (“The Progress of Peoples”) that emerged in the years following the Second Vatican Council.

Pope Francis has used language similar to that in the encyclical in his admonitions of the world economy and his vision for a more merciful world.

Released March 26, 1967 — perhaps purposefully on Easter — Blessed Paul’s encyclical rooted the Catholic Church in solidarity with the world’s poorest nations. He called for the elimination of economic disparity and reminded people to recognize the common threads that unite humanity in a world with finite resources.

“We are the heirs of earlier generations, and we reap benefits from the efforts of our contemporaries; we are under obligation to all men,” Blessed Paul wrote in his only social encyclical. “Therefore, we cannot disregard the welfare of those who will come after us to increase the human family. The reality of human solidarity brings us not only benefits but also obligations.”

[hotblock]

Such a call has repeatedly echoed throughout Pope Francis’ four-year pontificate. A reading of his apostolic exhortation “The Joy of the Gospel” (“Evangelii Gaudium”) and his encyclical on the environment and human development, “Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home,” he reminds the human family of the social responsibilities to care for one another. In line with Blessed Paul, he has repeatedly recalled the social injuries caused by an “economic system that has the god of money at its center,” as he said in a message to the U.S. Regional World Meeting of Popular Movements in Modesto, California, in February.

While 50 years have passed and the political discussion has shifted to new issues, the message of “Populorum Progressio” has been resurrected in a 21st-century pope and remains as important today as it was in 1967, social policy experts told Catholic News Service as the encyclical’s golden anniversary approached.

“‘Populorum Progressio’ and the whole idea of integral human development is really the cornerstone of everything since (then) in the church,” said Dana Dillon, assistant professor of theology at Providence College.

(CNS photo/Giancarlo Giuliani, Catholic Press Photo)

The message, if not the specific words, has resonated through the pontificates of St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, but it is Pope Francis who has renewed the call for true human development in a world still experiencing economic inequality and vast pockets of extreme poverty, said Leonard Calabrese, retired executive director of the Commission on Catholic Community Action in the Cleveland Diocese.

“It’s not only about economic development. It’s also about distributive justice and a concern for fairness for how development and the benefits of development are spread through the society,” Calabrese said, comparing the similar calls from both popes.

Jesuit Father Drew Christiansen, distinguished professor of ethics and global development at Georgetown University, called Pope Francis a “Paul VI pope” because of his reliance on the Holy Spirit in calling the world to mercy and justice.

The timing of the encyclical’s release — less than 16 months after Vatican II concluded — fed eager laypeople and clergy to go into the world to share the good news through action. Not only did Blessed Paul announce the formation of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace then, but the document inspired the introduction in 1969 of what today is the U.S. bishops’ Catholic Campaign for Human Development and gave birth to social action offices in many dioceses.

“It had carriers all over the world who were sympathetic to the mood of the council and the themes of the church’s involvement in the world of the council. It energized the church and many people in the development field,” Father Christiansen said.

[hotblock2]

Massimo Faggioli, professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University, suggested it was time for the church to take a deeper look at “Populorum Progressio” at this point in the church’s history. “It is relevant because it is a time to rediscover what was the most radical Catholic social teaching of these last 50 years,” he told CNS.

The document raised the profile of the church’s concern for people in the global south at a time when European colonialism was declining, giving people across Africa, Asia and Latin America greater hope that the church was with them, Faggioli explained.

In the global north, however, the encyclical was panned. Vermont Royster, editor of The Wall Street Journal at the time, called it “warmed-over Marxism” because it challenged capitalism’s inherent rush to achieve profit at the expense of human life. Others were critical of Blessed Paul VI’s assessment that economic trade must benefit both the developed countries and those emerging from the colonialism that had dominated the world for centuries, feeling it was too judgmental of existing corporate practices.

Samuel Gregg, director of research at the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty in Grand Rapids, Michigan, writing for Crisis Magazine March 3, questioned why Blessed Paul addressed such questions specifically. He questioned the prudential judgments offered by Blessed Paul about such matters because “there’s often no single right answer for Catholics.”

Still, he credited Blessed Paul for his emphasis on core church teaching on integral human development.

“Paul VI reminded us that while human development has a material dimension, it cannot be reduced to material growth,” Gregg wrote in an email to CNS. “We fully develop when we freely choose the goods that are distinctly human and act accordingly. If Catholics lose sight of this truth when we talk about topics ranging from justice to the decisions of political and business leaders to the environment, then we will have nothing distinctive to say about human development.”

While the particulars of trade deals may have shifted over the last half-century, the overall issue of the importance of building relationships among people in developed and undeveloped nations remains, said John Carr, director of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University.

[hotblock3]

Blessed Paul envisioned that economic development could lead to long-lasting peace, Carr said. “Development and justice is more a matter of being more than having more. Being more a worker, being a husband, mother, a citizen,” he said.

Carr points particularly to paragraph 47 of the encyclical as a vital passage that raises questions that resonate today as they did in 1967. In the passage, Blessed Paul explained that simply ending hunger and reducing poverty was not enough. He called on people to build a human community across borders, cultures and economic classes.

Blessed Paul continues: “On the part of the rich man, it calls for great generosity, willing sacrifice and diligent effort. Each man must examine his conscience, which sounds a new call in our present times. Is he prepared to support, at his own expense, projects and undertakings designed to help the needy? Is he prepared to pay higher taxes so that public authorities may expand their efforts in the work of development? Is he prepared to pay more for imported goods, so that the foreign producer may make a fairer profit? Is he prepared to emigrate from his homeland if necessary and if he is young, in order to help the emerging nations?”

Carr said the same questions deserve consideration today.

“Candidly,” he told CNS, “the contrast between the dominant message in Washington and the call of the church could not be more stark.”

PREVIOUS: Encyclical’s influence on church’s social action work continues

NEXT: World needs those who can bring God’s hope, consolation, pope says

Share this story