NEW YORK (CNS) — Most Americans would be hard-pressed to name boxing’s current heavyweight champion. Yet, for most of the 20th century, that person was a central figure in our national life.

NEW YORK (CNS) — Most Americans would be hard-pressed to name boxing’s current heavyweight champion. Yet, for most of the 20th century, that person was a central figure in our national life.

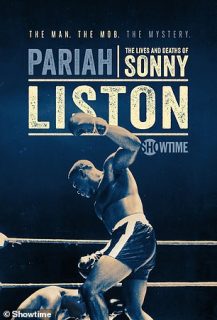

As recalled by the documentary “Pariah,” Charles “Sonny” Liston (c. 1930-1970) — who became champ as the civil rights movement intensified — is a case in point.

Subtitled “The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston,” the moderately engaging film premieres on the Showtime pay-cable channel Friday, Nov. 15, 9-10:30 p.m. EST.

British filmmaker Simon George traces the boxer’s journey from his depression-era roots in Arkansas to his untimely and tragic demise in Las Vegas. Wonderful, starkly evocative photographs and archival footage enhance the narrative. George also employs dramatic reenactments, which don’t contribute as much.

Retired boxer Mike Tyson, who is often compared to Liston, is the only fighter among the numerous commentators. Ironically, Tyson’s trainer, Cus D’Amato, had earlier trained Floyd Patterson, the man Liston defeated for the heavyweight title Sept. 25, 1962.

[hotblock]

Other interviewees include Charles Farrell, a self-confessed fight fixer, and retired Las Vegas detective Larry Gandy — who, some believe, was hired to kill Liston. This shady cast of characters lends “Pariah” the spice that refreshingly distinguishes it from more staid programming.

Horrific is scarcely adequate to describe Liston’s childhood. He was the 24th of 25 children raised by sharecropper Tobe Liston and his wife, Helen. When he was big enough, Liston was harnessed to a plow to do the work of a mule.

The relentlessly sadistic father’s whippings left lifelong scars on the boxer. “If he missed a day,” Liston said, “I’d feel like saying: ‘How come you didn’t whip me today?'”

Escaping his misery, Liston hitchhiked to St. Louis, where Helen had recently moved. According to the filmmakers, however, she wasn’t thrilled about having another mouth to feed. Left to the streets, Liston resorted to criminality. By 1950, he was serving time in the state penitentiary for armed robbery.

There, Liston met Catholic priest Father Alois Stevens, who encouraged him to try boxing. Released in 1952, Liston used his connections to mobsters Frankie Carbo and Frank “Blinky” Palermo to ascend the ranks of the sport.

[tower]

Despite Liston’s stated intention to be a “decent, respectable champion,” observes sports journalist Robert Lipsyte, “he became a symbol of the champ we didn’t want.”

Yet by the time of Liston’s two definitive fights with Muhammad Ali in Miami Beach in 1964 and Lewiston, Maine, in 1965, Ali — who had famously joined the Nation of Islam and changed his name from Cassius Clay — was seen as the greater threat to the white establishment. Fighting Ali, says history professor Hasan Jeffries, gave Liston his chance to become “a hero by shutting this dude up.”

Images of violence, both inside and outside the boxing ring, mature themes, including adultery and drug addiction, partial nudity incidental to a scene of breastfeeding, and occasional coarse language add up to make “Pariah” best for adults.

George’s film does a good job contextualizing the fighter’s backstory and correcting the misperception that he was vicious. Nigel Collins, former editor-in-chief of Ring magazine, says Liston was “very sensitive and could be hurt easily.” But the memorable footage of the champ enthralling a smiling infant girl he holds in his massive arms counters the error better than words.

Understandably, the documentarians speculate about Liston’s mysterious death. Did he succumb to an overdose, as the police concluded, or was he murdered? But viewers will wish George and his collaborators had assessed Liston’s place in history more thoroughly. “Pariah” is, nonetheless, a relatable, sympathetic portrait of its subject.

***

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Women’s history of Christianity does disservice to Catholic beliefs

NEXT: ‘Doctor Sleep’ writes a prescription for bad dreams

Share this story