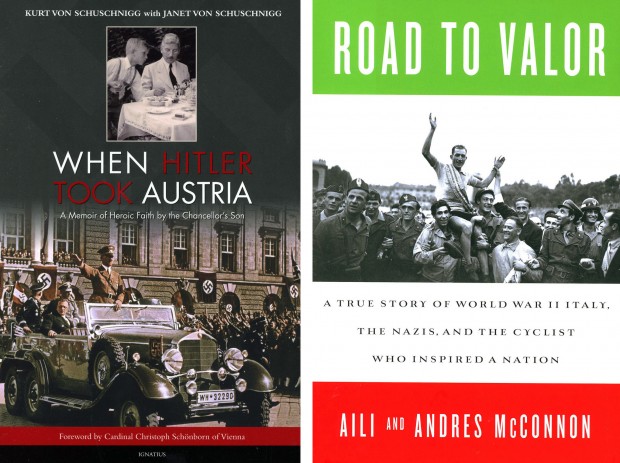

“When Hitler Took Austria: A Memoir of Heroic Faith by the Chancellor’s Son” by Kurt Von Schuschnigg with Janet Von Schuschnigg. Ignatius Press (San Francisco, 2012). 306 pp., $24.95.

“Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II Italy, the Nazis and the Cyclist Who Inspired a Nation” by Aili and Andres McConnon. Crown (New York, 2012). 352 pp., $25.

“When Hitler Took Austria” is the memoir of Kurt Von Schuschnigg, the son of the chancellor of Austria between 1934 and 1938.

Young Kurt grew up in a world of aristocratic privilege, cosseted by his mother, Herma, and nanny, Fraulein Alice. Kurt’s father, also Kurt Von Schuschnigg, struggled in those years to keep Austria from being annexed by Adolf Hitler into “Greater Germany.” But Hitler, determined to possess the country of his birth, invaded Austria March 12, 1938, and was greeted by rapturous crowds.

Young Kurt, born in 1926, was only 12 when the Auschluss occurred, but his world had already been rocked three years before when his mother was killed; her car had been driven into a tree by a saboteur acting as chauffeur. Kurt’s father had remarried by the time of the annexation to Germany to another Austrian aristocrat, Countess Vera Fugger-Babenhausen.

[hotblock]

Vera became a tireless advocate for her husband when he was imprisoned in Austria and visits were difficult to arrange. Vera shared his imprisonment when the family was moved into Germany and, finally, to the concentration camp, Sachsenhausen. Although the family was housed in a small cottage on the edge of the camp, separated from the main camp by a high wall, they were fully aware of the horrors being perpetrated on the prisoners nearby because of the screaming, which could not be silenced by the blackout curtains.

The former chancellor had to stay within the barbed-wire confines of Sachsenhausen, but Vera and her stepson, Kurt, could come and go, an important advantage when food became ever scarcer. Besides providing protein by fishing, young Kurt also traveled regularly to Berlin to bring the consecrated host to his father.

But in early 1943, when it was already clear the war was going badly for the Germans, young Kurt was forced to join the armed forces. The navy was considered the safest branch of the services as they could not be sent to the Eastern front, but this safety proved to be illusory when Kurt’s ship was sunk in 1944 and he was badly burned and injured. Determined to never be trapped on a boat again, Kurt escaped from his hospital in Konigsberg in the north of Germany and began his journey across the chaotic, bombed-out landscape of Germany in 1945.

Lacking legal documentation and traveling papers and facing instant execution if caught as a deserter, Kurt slowly moved south toward the mountains of the Tyrol where he planned to hide until the war’s end. But, fortunately in early 1945, after crisscrossing Germany, he was put into the hands of resistance fighters by a relative. They arranged for Kurt to cross over the mountains into Switzerland.

Kurt’s parents also survived the deprivations of Sachsenhausen and, after the war, emigrated to Italy. “When Hitler Took Austria” is an amazing story of adventure and survival, but it is not a story where Catholicism or the Christian faith plays a vital role.

In contrast, “Road to Valor,” the story of Gino Bartali, the great Italian cyclist, is a story where Catholicism plays a central role.

Bartali won the Tour de France in 1938 (the last time it was run until after the war) and again, 10 years later, in 1948. While others have now won the grueling, multi-part Tour de France more than once, no one has done it so many years apart.

Bartali was a fervent Catholic and, through his international fame at a young age, was acquainted with many in the highest circles of the Catholic hierarchy. It was through his friendship with Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa of Florence that Bartali was led into the Italian resistance. Bartali would carry forged identification papers in his bicycle seat between cities in the Nazi-occupied sector of Italy. In Italy as it was in Germany, traveling without the proper papers was dangerous for anyone, but for Jews, who had lost their status as citizens in Italy, being caught without papers meant deportation and death.

Through most of the war, Bartali kept a low profile as he was not eager to serve in the Fascist armies of Mussolini or, later, under the Germans. But occasionally while he was in the resistance, he would distract station workers and police as trains pulled into stations (the moment of greatest danger for those traveling illegally) by revealing himself as the international cycling star, creating a furor with adoring fans and allowing trains to pass unchecked.

The authors of “Road to Valor” are the brother and sister team of Aili and Andres McConnon. Aili was a staff writer for Business Week and her brother is a filmmaker who also has done historical research for several books. While they deserve credit for bringing to light the story of Bartali’s wartime activities which remained secret for decades, one could wish they wrote more graceful English.

Describing Bartali’s wedding, the authors write, “They (the wedding couple) embraced of one the most sacred sacraments in the Catholic faith.” Another cyclist resists Bartali’s attempts to throw him off his lead in a race with “unyielding fluidity that refused to be baited.”

Despite these and other clunkers, the story of Gino Bartali is a fascinating one. He was a competitive man who sought fame tirelessly as a cyclist, but remained completely silent on his work that saved hundreds of lives.

***

Yearley holds a certificate of advanced study in theology from the Ecumenical Institute at St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore.

PREVIOUS: Clint Eastwood still on his game in ‘Trouble With the Curve’

NEXT: How Aristotle would look at today’s parenting challenges

Share this story