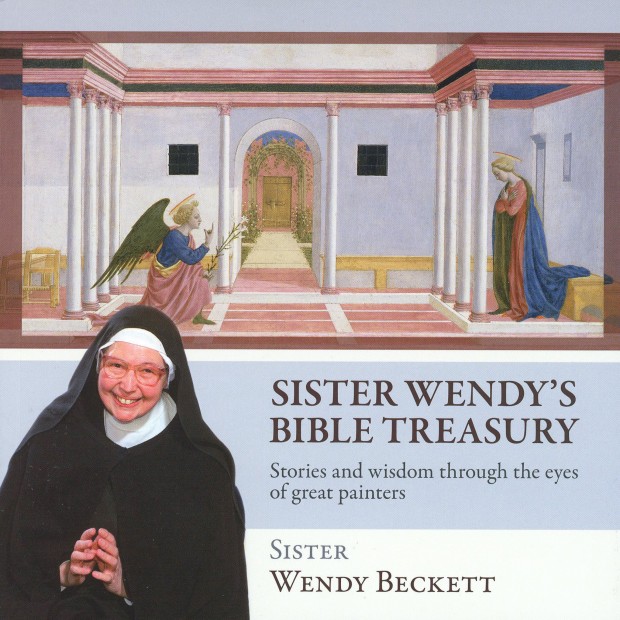

“Sister Wendy’s Bible Treasury: Stories and Wisdom Through the Eyes of Great Painters” by Sister Wendy Beckett. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, N.Y., 2012). 228 pp. $35.

Sometimes good ideas don’t click in practice, as is the case with this book. For adolescents and young adults, it could have been an excellent introduction to understanding masterpiece paintings as well as biblical stories and themes.

The idea was to show how great paintings over the centuries have conveyed core biblical beliefs and events.

The interlocutor is Sister Wendy Beckett, a South African-born nun whose TV shows on art criticism have drawn widespread praise making her a popular art connoisseur in Great Britain and the United States.

Yet the book bogs down. This is mostly because of the lengthy excerpts from the stilted, archaic English prose and poetry of the King James Bible. While the King James is an important work in the history of Bible translations, its 17th-century British English sounds strange to modern U.S. readers, slowing down the narrative. Nobody “spoke” in this version. They “spake” to each other. Men and women didn’t have sexual relations. They came “unto” each other.

Sister Wendy is a contemplative nun living in a Carmelite convent in Norfolk, England, and author of numerous books on art, prayer and meditation. She does her part to make the book’s concept work. She writes concise critiques for many of the 54 paintings in the book, relating them to the accompanying biblical verses.

We learn, for instance, how the 15th-century Italian painter Masaccio depicted the meaning of Adam and Eve being expelled from Paradise. Adam covers his eyes with his hands because he “cannot bear to look at what he has done” while Eve, her face contorted, “flings back her head in the anguish of the primeval scream.” Masaccio, Sister Wendy tells us, conveys “what it means to leave a world of peace and freedom” and move into one of “violence and unhappiness.”

Another positive feature of the book is the high-quality glossy reproductions of the paintings.

Sister Wendy also writes brief introductions to each chapter of excerpts, giving a straightforward, no-nonsense summary of the biblical and theological themes developed in the verses. But there is not enough of Sister Wendy in the book. Many of the paintings are without commentary and many of the biblical excerpts are unaccompanied by paintings.

The book might have worked better with modern-day English paraphrases of the biblical stories instead of the King James excerpts. This might also have helped another aim of the book: to entice people to read the entire Bible.

***

Bono is a retired CNS staff writer.

PREVIOUS: Video game review: New ‘Super Mario Bros. 2’

NEXT: ‘Wreck-It Ralph’ looks for goodness among video-game bad guys

Share this story