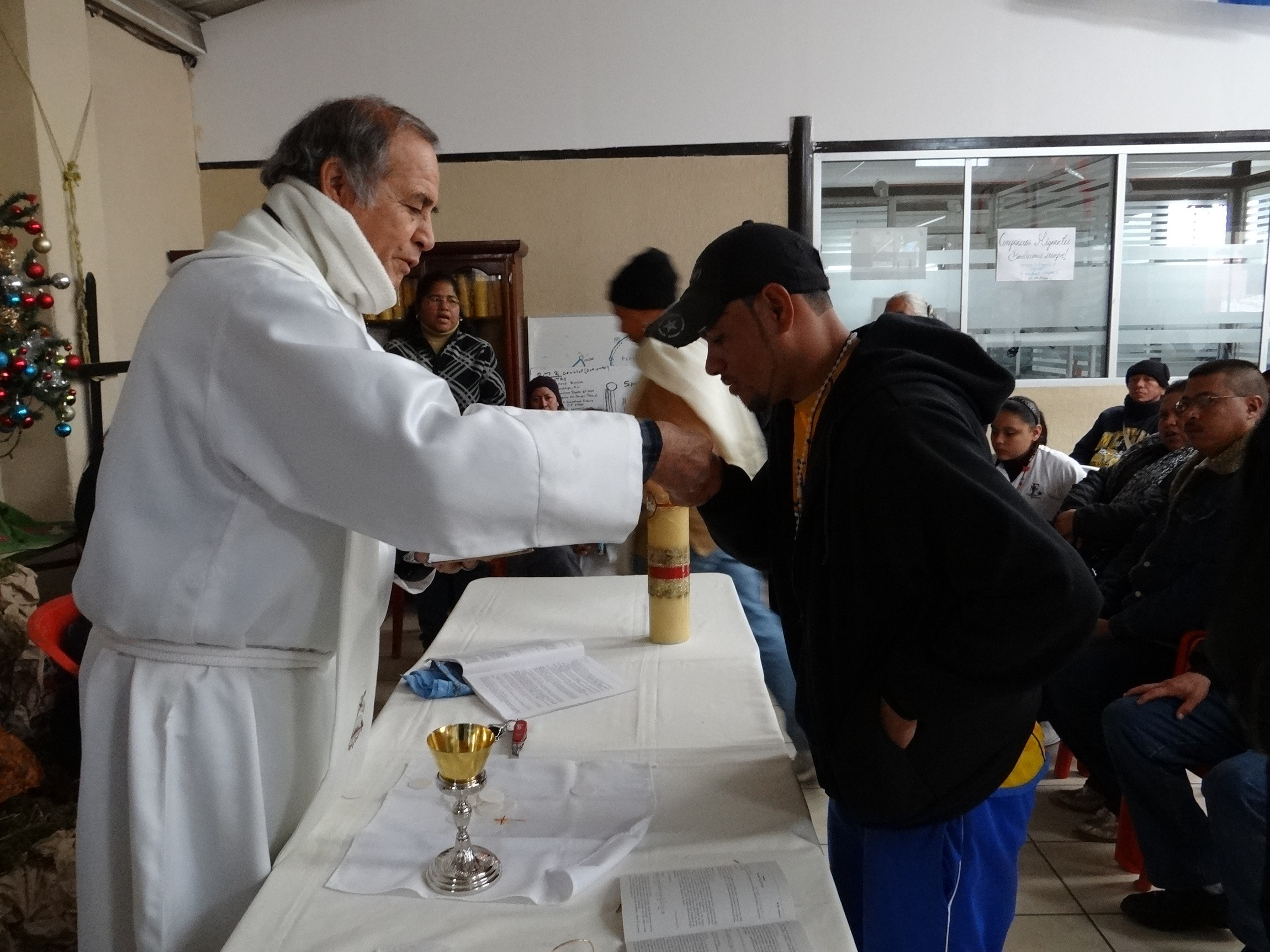

SALTILLO, Mexico (CNS) — During Mass on the feast of the Epiphany, Father Pedro Pantoja asked a group of parishioners in attendance to pray for his Central American guests — all of whom were seeking to sneak into the United States.

“We want you to pray for peace,” Father Pantoja instructed. “They need peace for a violent journey.”

The migrants seeking shelter in Saltillo, about 190 miles south of the Texas border at Laredo, arrived after a perilous path through Mexico, where often criminal gangs — sometimes assisted by complicit and corrupt police and public officials — exploit, extort and kidnap them.

[hotblock]

Father Pantoja said the migrants cling to their Christian faith along the way and often invoke a higher power for protection. Yet he said “99 percent” of the guests arriving at his shelter are not Catholic; only three of the approximately 50 migrants attending the Jan. 7 Mass received Communion.

The priest, founder of two migrant shelters, expressed no dismay at the religious confessions of his guests. He said he prefers instead to view the arrival of so many evangelicals as an opportunity to show the best of the Catholic Church, which is often attacked and belittled by pastors in Central America. There, populations have increasingly converted to non-Catholic religions.

(The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is commemorating National Migration Week Jan. 6-12. Learn more here.)

“I offer them bread and do so freely,” Father Pantoja said. “The origin of this is love and a social commitment, not a debate about faith.”

The arrival of so many non-Catholics at the Saltillo shelter — known as Belen, Inn of the Migrant — reflects the inroads made by evangelical groups in Central America, where Father Pantoja says the conversions often come by means of offering potential economic progress for impoverished peoples.

“It’s an embarrassment for the Central American church that it hasn’t reached the poor in their enormous numbers,” he said.

Locally, relations between Catholics and evangelical leaders often have been unfriendly. Father Pantoja said he has reached out to his evangelical counterparts to work on migrant matters, but said he received no response, “because I’m not an interlocutor for them as a priest.”

But he’s working to change perceptions, mainly by meeting migrants’ most basic needs — often at great risk. Father Pantoja and shelter staff recently received death threats; criminal groups such as Los Zetas have attempted to enter his shelter, which serves an increasingly violent city.

Catholics operate migrant shelters stretching the length of the country, from Chiapas and Tabasco in the South to Tijuana and the Texas border in the North. Father Pantoja has established a network in which the shelters communicate with each other, allowing them to keep track of how many migrants have entered the country and how they’re progressing as they steal rides on northbound trains.

“(Undocumented Central Americans) realize the reality of all the migrant shelters, of all the priests belonging to the Catholic Church. … They understand this, but we don’t talk about it,” he said.

Migrants in Saltillo expressed appreciation for the assistance they received from Catholics on their trips.

“I’m evangelical, but I like the Catholics. They’re about the only ones that support Central American migrants,” said Honduran migrant Gerardo Bueso, 26.

Bueso was deported twice from the United States, but is heading north yet again, despite the dangers of transiting Mexico and a sagging U.S. job market, which he says offers better opportunities than the violence and poverty of Honduras.

Father Pantoja often hears such stories.

“The latest reason for the migration is poverty, hunger and violence,” he said.

“A poor migrant, (if he) is able to work in the United States and gets $100, with this, he can live an entire year,” he added.

In his homily for the feast of the Epiphany — when Mexicans give gifts and traditionally share a special ring-cake and hot chocolate with their families — the priest compared the migrants to baby Jesus and the authorities, criminal groups and anti-immigrant groups to Herod.

“You, too, are a threat to an empire,” Father Pantoja said. “In some way, we’re a threat to the powerful.

“Jesus at Bethlehem became a forced migrant, too,” he said. “This is your story.”

Parishioners later served chocolate-flavored “atole” and tamales, a treat usually reserved for Candlemas, Feb. 2.

Father Pantoja expressed no doubts that the church’s hospitality is changing perceptions about Catholics.

“Pastors have come here and changed their vision,” he said. “They’ve told me: ‘I’m going to stop attacking the Catholic Church.'”

PREVIOUS: Like Good Samaritan, help those in need, pope says in message for the sick

NEXT: Partnerships key to Haiti’s recovery 3 years after earthquake

Share this story