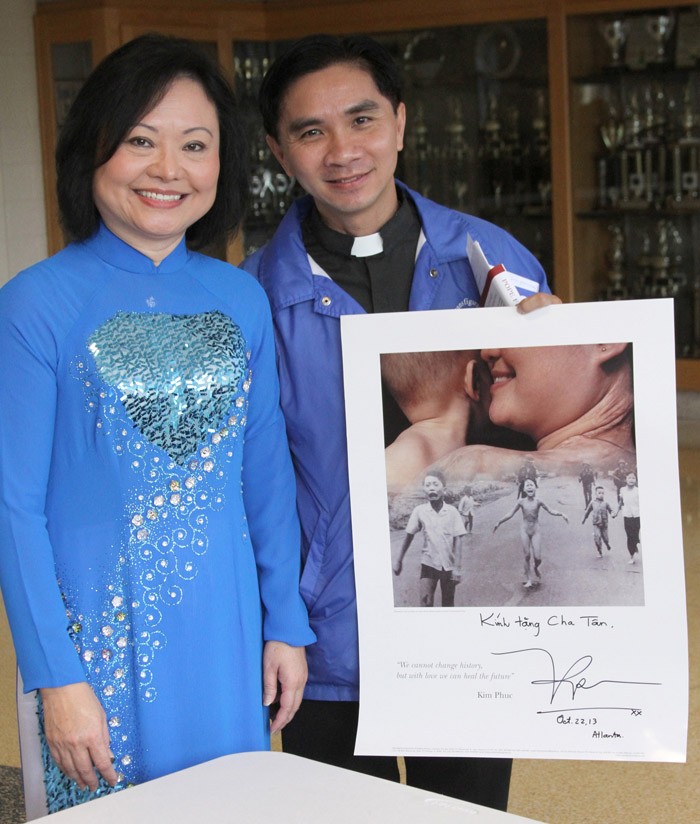

Vietnam War survivor Kim Phuc Phan Thi shows some of the scars she still bears from a 1972 napalm bomb attack leveled upon innocent civilians in her Vietnamese village, Trang Bang. (CNS photo/Michael Alexander, Georgia Bulletin)

ATLANTA (CNS) — An entire generation instantly recognizes the image of an unclothed Vietnamese girl running toward the camera in terror after a bombing at her village.

Taken by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut in June 1972, the black and white photograph became one of the most iconic pictures from the Vietnam War.

Napalm bombing survivor Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the girl from the picture, visited Marist School in Atlanta and asked the students to help spread a message of peace and forgiveness.

Dressed in a traditional Vietnamese dress, Phuc delivered a soft-spoken yet mighty testimony during her October visit.

“I came through the fire and I am blessed to be here,” said Phuc.

Students, faculty and guests gathered in the school’s Centennial Center to hear Phuc’s presentation of “Love, Hope and Forgiveness.”

She was 9 years old when the attack occurred. She and her family had been hiding in a Buddhist pagoda in Trang Bang and she was severely injured with third-degree burns over much of her body. Phuc’s clothing was burned off by the intense heat of napalm.

A sticky gel-like substance, napalm was used in incendiary bombs and flamethrowers and contained gasoline and soaps.

Ut captured the scene of Phuc and other children fleeing down a road and then immediately drove her and others to a South Vietnamese hospital. His photograph won a Pulitzer Prize.

Phuc underwent 17 surgeries in 14 months before returning home. She is one of few napalm victims to survive burns as the substance can reach temperatures of more than 1,500 F. Phuc’s infant cousins died in the attack.

[hotblock]

Phuc, who now lives in Canada with her husband and teenage sons, told Marist students that patiently practicing daily prayer helped her to forgive.

“It wasn’t easy,” she said. “All of you can do it here, too.”

Her presentation included a clip from a Canadian documentary featuring her 1996 visit to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. Army Capt. Ron Gibbs, who served on the board of the memorial fund, invited her to a Veterans Day event.

Phuc told the audience at the memorial that if she could meet with the pilot responsible for the attack, she would forgive him, saying we “cannot change history,” but should all try to do good things.

Capt. John Plummer was there that day. “I knew also that extended to me,” said Plummer in the documentary. He believes he helped coordinate the bombing and said the intended targets were nearby enemy bunkers, not the village.

When Plummer read about the bombing in the newspaper Stars and Stripes, he said it was like being “hit with a baseball bat.”

Upon his return home from Vietnam, Plummer struggled with alcoholism and broken marriages.

He said he knew his struggles would continue, “until I reconcile with Kim somehow.” He passed a note to a National Park Service policeman at the memorial, hoping to get the chance to meet with her after the ceremony. A friend helped facilitate the meeting.

“It was really touching,” said Plummer in the documentary. “The entire world has lifted off my shoulders.” Now a Methodist minister, Plummer said he knew Kim would see his sorrow and know it was from his heart.

“We became good friends,” said Phuc of her relationship with Plummer. “It was truly reconciliation.”

The path for Phuc has been long though, and several things have helped in healing, including her family, her relationship with God, and seeking asylum in Canada.

After her surgeries, Phuc returned to her village, suffering from pain and severe headaches. Later, the local government removed her from school, forcing her to serve as a symbol of the state.

In 1986, Phuc went to study in Cuba and met and married Bui Huy Toan. Phuc and her husband sought political asylum in Canada during a wedding trip stopover in Newfoundland.

She knew nothing about Canada, but the newlyweds immersed themselves in the culture, learning English, volunteering, working and seeking education. They used food subsidy not to buy food, but to ride a bus to school.

“They adopted us,” she said of the Canadian people. Her life there is “so peaceful and wonderful,” Phuc said.

Phuc also talked about how her sons, Thomas and Stephen, ages 16 and 19 respectively, helped her in healing emotionally.

When Thomas was just learning to speak, he noticed his mother’s scarred arm while she was wearing a short-sleeve shirt. Thomas asked, “Mom hurt?” Then the toddler kissed his mother’s scars.

“It really touched my heart,” said Phuc.

“They pray for me,” and through FaceTime, she can talk with them when traveling.

Phuc, who takes more than 40 trips a year to speak about peace and the work of her international foundation, uses the technology to keep in touch.

“You still have to share your mom with the world,” she tells her sons.

The Kim Foundation International is a nonprofit organization that funds medical care and psychological assistance for child victims of war. Its current project is building a pediatric and corrective surgery recovery ward in Uganda, where the people have experienced two decades of war, disease and high HIV rates.

“I came from war, and now I value peace,” she said.

Individually everyone must practice peace whether they are a world leader or an everyday person, said Phuc.

“People talk about peace, but they don’t know what they are talking about. … It’s in here,” she said, pointing to her heart.

– – –

Golden is on the staff of The Georgia Bulletin, newspaper of the Atlanta Archdiocese.

PREVIOUS: Vincentian pastor recalled for administering last rites to Kennedy

NEXT: Washington priest recalls narrating Kennedy’s funeral Mass on radio

Share this story