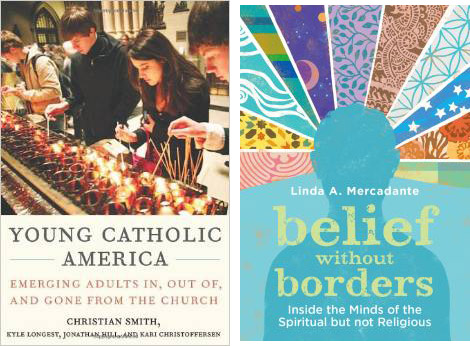

“Young Catholic America: Emerging Adults In, Out of and Gone from the Church”

by Christian Smith, Kyle Longest, Jonathan Hill and Kari Christoffersen.

Oxford University Press (New York, 2014).

274 pp., $29.95.

“Belief without Borders: Inside the Minds of the Spiritual but not Religious”

by Linda A. Mercadante.

Oxford University Press (New York, 2014).

258 pp., $29.95.

Since its inception in 2002, the National Study of Youth and Religion has provided church ministry practitioners a goldmine of valuable information about the religious beliefs and values of young people and their parents. The first full report of the study was published in “Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers” (2009) by Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton. Several additional books have followed as that data was unpacked.

The young people who participated in the original study in 2002 have now grown into young adults. The researchers have now gone back to these young people to collect data on their present-day religious lives. The data from the most recent study is presented in the book, “Young Catholic America: Emerging Adults In, Out of and Gone from the Church,” which is again written by Smith, the lead researcher, along with several of his research colleagues.

[hotblock]

For those engaged in ministry within the church or for those concerned with the state of religion in the United States, the writing of Smith and his team remain “must reads.” Captured here is a snapshot of where Catholic young people between the ages of 22 and 28 currently are in their relationship with the church and how they express their faith.

The findings are interesting. Emerging adults — those who are of age but who have not yet moved fully into adult responsibilities — hold religious and spiritual beliefs not too different from previous generations but may lack the language to express those beliefs. They also are much less likely to participate in weekly religious practices and have less of a commitment to the institutional church.

While recognizing the declining church membership among young people, Smith finds that marriage and having children seems to bring young people back to religious practice. The problem though is that many young people are delaying or avoiding marriage entirely.

While deftly written and solidly researched, “Young Catholic America” feels less compelling than the previous works in the series. As with all long-term studies it is important to remember that each “snapshot” reflects only that period of time and not the end of the journey. It will be interesting to follow these young people as they move into full adulthood.

In “Belief without Borders,” Linda A. Mercadante presents a qualitative study of the religious and spiritual attitudes of adults who are “spiritual, but not religious.” Developed from 85 in-depth interviews conducted by the author, the book presents the thoughts of those interviewed primarily in their own words.

According to Mercadante, people who are spiritual but not religious generally fall into five categories or types: dissenters, casuals, explorers, seekers and immigrants. Thus some of them reject the church and its teachings for some reason, while others have at least some ongoing relationship with religion.

Mercadante notes that people who are spiritual but not religious can be found in every age and stage in life, although a steep decline in religious practice can be traced to the 1960s and ’70s. One of the critical factors for this change seems to be the developing principle that everyone is “free to adopt, adapt, discard and change any spiritual or religious beliefs they encountered.” The author suggests that this phenomenon is consistent with the findings of Robert Bellah in his 1985 seminal work “Habits of the Heart.”

Mercadante further notes that “People … have claimed for themselves the authority formerly ceded to others. This does not necessarily imply a rejection of the social order, nor even a call for radical social change. But it does include a taking back of authority over what beliefs to accept and to reject, what to have faith in, how to practice one’s faith, and what criteria by which to judge the self.”

Mercadante provides here a fascinating look into the attitudes of people who are spiritual but not religious. While the author doesn’t draw many conclusions from these interviews, the valuable data is clearly presented for others to use and learn from on their own. While a bit of a slog to get through, what can be learned from the effort is well worthwhile.

***

Mulhall is a catechist. He lives in Laurel, Maryland.

Share this story