BALTIMORE (CNS) — Father Dick Lawrence doesn’t see homeless people through rose-colored glasses, but he doesn’t close his eyes to them either.

“They didn’t get there overnight and you’re not going to get them out (of homelessness) overnight,” said the pastor of St. Vincent de Paul Church in downtown Baltimore. “Sometimes the best you can do is to treat them like human beings and provide effective support services to keep them from declining further and faster.”

(See a related video)

Father Lawrence and the congregation of his urban parish, in partnership with the congregation of suburban Our Lady of the Fields Church in Millersville, Maryland, have been doing that for more than 20 years.

Every Friday night, St. Vincent de Paul hosts a dinner for anyone who wants a hot meal. Deacon Ed Stoops and his cadre of volunteers from Our Lady of the Fields bring the food and join St. Vincent parishioners in setup and cleanup each week.

“Tonight we are expecting to serve about 150 poor and homeless,” Deacon Stoops told Catholic News Service on a recent Friday. “Last week at the end of the month we had 316 people, but now it’s the beginning of the month and the checks are in, so we’ll have fewer people.”

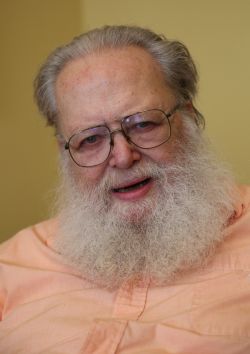

Father Dick Lawrence, pastor of St. Vincent de Paul Church in Baltimore, poses for a photo in early July. (CNS photo/Bob Roller)

The deacon, along with his wife and daughter, started the weekly meals for poor and homeless people 22 years ago. “It’s been our great privilege to meet Jesus in his poor and homeless people,” he said.

But the meals are just a small part of the services provided at St. Vincent de Paul for the poor and homeless. When the city of Baltimore put a small park next to the church up for sale, the parish bought it and it has now become what outreach worker Dwayne Tony Simmons calls “a safe zone” for the homeless.

“This church is like our safe haven,” said Simmons, who is himself homeless but operates a street newspaper called Word on the Street and works for an organization called Faces of Homelessness Speakers’ Bureau.

“If you’re hungry, you can come here,” he added. “If you need clothing, you can come here. People are very generous and they know they can find people if they come to this park. And it protects you. It gives you a sense of peace when you’re sitting in this park.”

Backed by the Baltimore Archdiocese, Father Lawrence stood up to the city when officials threatened to arrest anyone who slept overnight in the parish-owned homeless encampment. The priest said he told Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, “You have your choice of who you lock up first, but I guarantee you who the second person will be.”

A compromise reached with the city requires that the park be cleared for cleaning from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. each day and that no tents or permanent structures can be set up on the site. Father Lawrence said the no-tents policy is safer for everyone, because some tents had been taken over for drug dealing or other illicit activities.

[hotblock]

Although those at the park are encouraged to go to the city-run homeless shelter when the temperature drops, “even on the coldest night we won’t tell people they have to leave and we won’t lock them up,” Father Lawrence said. “Giving people a place to sleep is one of the basic human needs.”

The parish also provides clothing for the homeless and helps to find furniture and household goods when someone is able to find housing. Homeless people are welcome at Masses and at the parish’s Sunday coffee hours, although there are two rules: “You can’t leave with more than two doughnuts and a cup of coffee, and we don’t ask each other for money,” Father Lawrence said.

Simmons said there are 4,088 homeless people in Baltimore on any given night. Nationwide, the figure is 610,042, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

Many of them are employed, and more than 220,000 of them are people in families, the alliance says.

Across the country in Oregon, 20-year-old Brittney Sparks is hoping to end the cycle of homelessness for herself and her two children. Raised by parents addicted to drugs and prone to violent fights, she spent part of her childhood in foster care and has been homeless off and on since 2009.

Dwayne Tony Simmons, a homeless outreach worker, poses in early July in a park outside St. Vincent de Paul Church in Baltimore. (CNS photo/Bob Roller)

Although she sometimes stays with friends or pays for hotels when she has work, she currently sleeps in her van in Milwaukie, Oregon.

“As a mother, you only want the best for your children,” she said. “It breaks my heart warming their dinner in a 7-11 microwave and eating on the floor of our van instead of a nutritious meal where we can sit around a table and eat together. I feel an overwhelming feeling of guilt. Guilt because I know my kids deserve the world and I can only give as much as I have, and it’s not enough.” She pawns belongings when she needs diapers, hygiene products or food.

Sparks has been a volunteer leader in a campaign led by Madonna’s Center to change housing laws for homeless teens in Clackamas County. The Catholic Campaign for Human Development has helped fund Madonna’s Center, which originated at St. John the Baptist Parish in Milwaukie.

When it comes to homelessness, youths are falling between the cracks, said Valerie Aschbacher, founder of Madonna’s Center and a member of St. John the Baptist. Teens with no rental history are blocked from getting into an apartment. The federal Housing and Urban Development agency can’t help teens, who are not recognized as legal guardians of their children. Even shelters won’t offer space to an unaccompanied youth with a child.

Run by volunteers, Madonna’s Center offers supplies like food and clothes to teen parents, plus job training, but Aschbacher and Sparks said good housing is the key step to emerging from poverty.

“People need to understand all of the barriers that come with homelessness,” Sparks said.

It’s hard to get a job with no access to your legal documents and no way to charge your telephone, she explained. She can’t afford child care and mostly she can’t focus on what she needs. There is not much chance for her to advance in education or work without stable housing.

“I wake up each day with one goal in mind,” she said. “Find a place for my kids and myself to lay our heads down tonight.”

***

Contributing to this story were CNS intern Sarah Hinds in Baltimore and Ed Langlois in Portland.

PREVIOUS: Archbishop Sheen’s sainthood cause suspended

NEXT: Cardinal backs St. Patrick’s Day Parade Committee as gay ban is lifted

Share this story