This Christmas season has not one but two new biographies of St. Katharine Drexel, each of which contributes in distinctly different ways to a fuller understanding of Philadelphia’s only home-grown saint.

This Christmas season has not one but two new biographies of St. Katharine Drexel, each of which contributes in distinctly different ways to a fuller understanding of Philadelphia’s only home-grown saint.

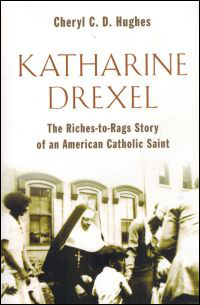

“Saint Katharine: The Life of Katharine Drexel.” Cordelia Frances Biddle; Westholme Publishing, $26; and “Katharine Drexel: The Riches to Rags story of an American Saint.” Cheryl C.D. Hughes; W.B. Eerdmans Publishing, $20.

“Saint Katharine: The Life of Katharine Drexel.” Cordelia Frances Biddle; Westholme Publishing, $26; and “Katharine Drexel: The Riches to Rags story of an American Saint.” Cheryl C.D. Hughes; W.B. Eerdmans Publishing, $20.

Both authors have a real affection and respect for Katharine, but because of their very different backgrounds they offer different insights into her.

Biddle, who spoke at a November celebration of St. Katharine’s birthday at the motherhouse of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, is a direct descendent of Anthony Drexel, Katharine’s beloved uncle who was the founder of Drexel University where she teaches creative writing. She brings a unique perspective to Katharine Drexel’s early life, as seen through the eyes of her extended family.

[hotblock]

Hughes, a professor of humanities and religious studies at Tulsa Community College, brings a theologian’s emphasis to the development and maturation of Katharine’s spiritual life.

Katharine Drexel was born in 1858, the second child of Francis A. and Hannah Langstroth Drexel, members of what was rapidly becoming Philadelphia wealthiest family through investment banking. Francis was a life-long Catholic; Hannah was Protestant, and the children were baptized Catholic.

Virtually all of the other Drexels in her father’s family, although born Catholic, also married outside the church but joined Protestant denominations. Her uncle Anthony was an Episcopalian, as is Cordelia Biddle, although she has great admiration for St. Katharine.

Within a month of Katharine’s birth and as a direct result of it Hannah Drexel died. Anthony and Ellen Drexel offered to take in the two little girls until Francis was in a position to care for them himself. In 1860 he married Emma Bouvier, a devout Catholic; the children were retrieved and were later joined by a new little sister, Louise.

The picture Biddle paints of their family life is rather austere with daily religious devotions emphasized as well as charitable outreach. There was little direct interplay with the parents who were rather remote, according to her family sources, leaving daily child rearing to the servants.

This she contrasts to the family of Anthony and Ellen Drexel, who although generous givers to charity, were compassionate and permissive parents who never denied anything to their children.

Consequently as adults their children never denied themselves. Anthony’s youngest son, George, in the early 20th century owned a 287-foot yacht with a crew of 100, Biddle reveals.

It was only at vacations with the other branches of the family that Elizabeth, Katharine and Louise could literally let their hair down. Katherine would fuss for hours over her dresses and innocently flirt with the young men who would join them, rather a typical teen.

This is the façade Katharine’s relatives saw; they were totally unaware of her inner struggle for perfection and a possible religious vocation which she shared only with her journal and her spiritual director, Bishop James O’Connor, a former Philadelphia priest who was then Bishop of Omaha.

Emma Drexel died in 1883 and Francis died in 1886, leaving the bulk of his estate in a trust fund for his three adult unmarried daughters. They could not touch the principal but were free to spend the interest however they wished.

Louise and Elizabeth ultimately married but continued following their parents’ example by devoting a substantial portion of their funds to charity, especially orphans and the disenfranchised.

When Katharine announced she was entering the convent, the extended family was aghast.

While Anthony Drexel was resigned to his niece’s choice, others were not.

His children and the other third-generation Drexels found themselves perplexed and even threatened by their cousin’s self abnegation. What she was undertaking — her decision to devote her life to the care of Native Americans and African Americans through a new Eucharistic-centered congregation — cast into high relief their self-indulgent lifestyles.

“Rather than embrace her courage they began carping that she was overly ascetic and more than a little odd,” Biddle writes.

Actually there were longstanding misunderstandings between the Francis Drexel family and the rest of the Drexel clan dating back to his marriage to Emma. For all of her charity, Biddle explains, she avoided family gatherings and not surprisingly some took this as a snub.

While Biddle is very good at citing sources in her writing, for these family matters she had to rely on the unwritten memories handed down through the generations. Some family members did not approve of Emma and in some cases, Francis or even Katharine, and it shows in the narrative.

But previous biographies relied almost solely on written material concerning St. Katharine’s early years which mostly suggest an idyllic childhood in a perfect family. In such matters the truth is generally somewhere between the two extremes.

Biddle is an excellent story teller who deftly follows Katharine in the context of the Civil War era through the Gilded Age and more than half a century leading the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament.

In discussing Katharine’s ministry Biddle certainly speaks of her spiritual qualities but most of the focus is on her social ministry, the work she did through her congregation and through other donations to improve the lives of Native Americans and African Americans.

These works are also covered in Hughes’ book, but in her case the major focus is on the spiritual motivation behind Katharine’s social outreach.

Hughes covers Katharine’s life in the first half of her book, but devotes the second part of it to her spirituality, which makes sense, because Hughes is a theologian by training.

No other biography of Katharine has done so to this extent, except perhaps the official Positio prepared by Father (now Bishop) Joseph Martino, which presented the case for her beatification and ultimate canonization or other unpublished writings not easily available to the general public. Much of the primary materials Hughes worked with are available in the archives of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in Bensalem.

Hughes devotes an entire chapter to what she calls the Kenotic and Eucharistic spirit of Katharine Drexel — Kenosis she defines as self-emptying so to be filled with Christ.

Katharine herself “would not have applied the term to her own spirituality because in her day it was not applied to ascetic theology,” Hughes explains.

“Her self-emptying kenotic spirit purposely balanced her Eucharistic spirituality; it was from her Eucharistic core that she was able to go forth to do battle with the inequities of her day, to fight for the right and education of Native Americans and African Americans. At the same time her main goal was to bring Native Americans and African Americans to Christ in the Catholic Church (emphasis added).”

St. Katharine Drexel was first and foremost an evangelizer; education was the beneficial tool she used to achieve that end. Hughes makes this very clear.

PREVIOUS: Sacred and human: New Washington art exhibit shows both sides of Mary

NEXT: ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ epic in scope, but a bit boring

Share this story