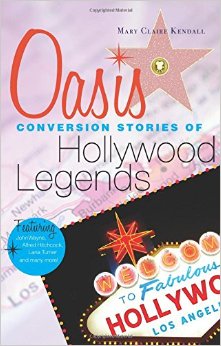

“Oasis: Conversion Stories of Hollywood Legends”

“Oasis: Conversion Stories of Hollywood Legends”

by Mary Claire Kendall.

Franciscan Media (Cincinnati, 2015).

224 pp., $16.99.

Presenting lives of a few Hollywood entertainers of the previous century as examples of Christian, and specifically Catholic, faith is fraught with peril.

Spiritual journeys are intensely personal and private. Additionally, those in the public eye are accustomed to shaping their own narratives for the widest possible audience, and all in Mary Claire Kendall’s “Oasis” used, during their lifetimes, publicists and ghostwriters adept at spinning a narrative of triumph over life’s pain and disappointments.

The public often whiffs the bunkum of the old traveling medicine shows when actors outside of a worship setting discuss their Christian beliefs. Hence, Stephen Sondheim’s acidly cynical lyric for an aging actress in “I’m Still Here”: “Reefers and vino, rest cures, religion and pills, and I’m here.”

Kendall doesn’t bother to extricate the hooey from the holy as she cobbles narratives from biographies, clips from newspaper obituaries and the occasional blog post from IMDb, a popular Internet source for movie, TV and celebrity news and information. She presents 12 compact life stories, with their connections, usually involving conversions during crises, to Catholic faith and practices.

[hotblock]

“During Hollywood’s golden age,” Kendall insists, “a proportionately higher number of stars gravitated to the Catholic faith.” She doesn’t provide documentation for this astonishingly hyperbolic claim.

Examined are Alfred Hitchcock (born and raised Catholic, and who never really left the faith); Gary Cooper, Jane Wyman, Susan Hayward and Ann Sothern (adult converts, some late in life, with Wyman’s coming after the death of an infant daughter); Ann Miller, John Wayne and Patricia Neal (deathbed baptisms); Lana Turner (childhood convert); Mary Astor (adult convert after the birth of a son); Betty Hutton (adult convert after years of alcoholism and bankruptcy); and, strangest of all, Bob Hope (baptized at age 93). Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, Ethel Barrymore and Spencer Tracy are briefly in the introductory mix.

Hope is the odd man out here both because Kendall writes instead of the Catholic faith of his wife, Dolores, and because he is the only one of these dozen who happily made religious references throughout his eight-decade performing life as a comedian.

Of course, the references had to be funny, and weren’t always about his frequent co-star Bing Crosby’s onscreen portrayal of priests. Sometimes they were about Dolores.

At a 1971 benefit for Cardinal Terence Cooke, a scripted quip: “You probably know that Dolores is a devout Catholic. For years, she thought Norman Vincent Peale was a stripper!”

Hope was known for straying from his marriage, but Kendall blithely sums that up by twice telling us that Dolores “toughed it out.” How does she know this? Just because there was no divorce? Dolores, who married Hope in 1934, presented nothing but a serene and placid exterior, and kept whatever suffering she felt and conflicts with her famous husband out of public view.

The best-composed chapter has Astor’s story about her many infidelities and alcoholism, because most of that originated with Astor herself, who was a formidably clear-eyed memoirist. But of her Catholic conversion, there’s almost no information, and her daughter Marylyn knows little other than a memory of her mother’s devotion to the Blessed Mother.

The only story with whom Kendall has a shared connection, through their friendships with Mother Dolores Hart, a former actress herself, is Neal’s. The husky-voiced actress, who endured a nervous breakdown, a difficult marriage to writer Roald Dahl, brain damage to her infant son from an accident, the measles death of one of her daughters and a stroke, found forgiveness from Maria Cooper Janis, the daughter of Gary Cooper. Neal had an affair with Cooper in the 1950s that resulted in an abortion, a devastating strain to Cooper’s Catholic family.

In 1978, Janis connected Neal to Mother Hart, who is now prioress of the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Connecticut. Mother Hart was responsible for getting Neal’s memoir, “As I Am,” published and offered spiritual advice to the troubled actress for decades.

“It was about a day before she died (in 2010) that she converted,” Mother Dolores remembered. At Neal’s burial, “a group of her buddies bade her farewell singing ‘Luck Be a Lady.'”

***

Jensen reviews movies for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Movie review: Inside Out

NEXT: Children’s reading: books to pray, learn with all summer long

Share this story