“We cannot love God when we do not appreciate or care for what God has made,” Cardinal Peter Turkson said Oct. 31 in an interview with the Catholic Times, newspaper of the Columbus Diocese. “This is what the pope wants people to understand.

“If the question is ‘What has God made?'” he continued, “the response is that the Bible says God created two things. God created the world and God created the human person, and those essentially are the two things we are talking about in this encyclical.

[hotblock]

“Whatever you want to call the pope’s message — integral ecology or something else — it is essentially an invitation to make our love for God show in what God has made.”

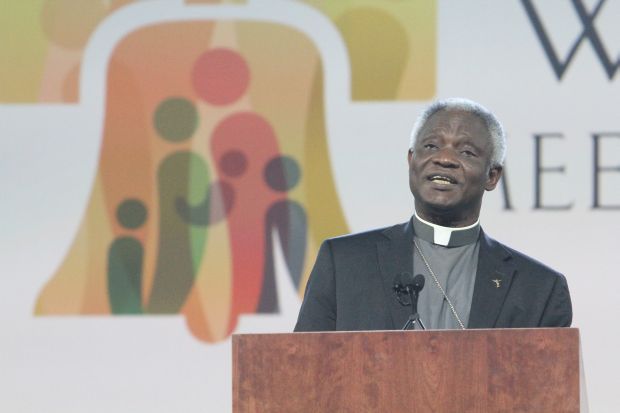

Cardinal Turkson, president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, took part in a panel discussion and question-and-answer session on the encyclical with representatives of Ohio’s political, business, scientific and spiritual communities at the Martin de Porres Center in Columbus.

The program was sponsored by the Catholic Conference of Ohio and the Catholic Climate Covenant and was part of a three-day visit to Columbus by the church’s first cardinal from Ghana.

On Nov. 1, he celebrated a Mass sponsored by the central Ohio Ghanaian community at St. Anthony Church. The following day, he spoke to students from throughout the area at St. Francis de Sales High School, visited Ohio State University’s Byrd Polar Research Center, and delivered at talk at to a capacity crowd at the university’s Mershon Auditorium.

His address was part of a series of events that the university is conducting relating to sustainability of the planet’s resources.

“An encyclical usually is something meant primarily for the Catholic community, but this was more of a secular letter, intended for the whole world because the pope was writing about subjects of universal concern,” Cardinal Turkson told the Catholic Times. “From his own ministry, he considers worthy of particular attention two things that are crying to us — the earth and the way we have abused it, and humanity, part of which is still needy and suffering.

“He puts the two together in a concern for creation and for the poor. The poor are not just those along the roadside who need money, but all of the forgotten people, the abandoned ones — the old, the homebound, the unborn. All of that is his concern.”

Cardinal Turkson told the audience of about 150 invited guests at the Porres center that stories in the secular media that describe “Laudato Si'” as mainly devoted to climate change miss the main point of the document.

“It’s not about climate change, but on human ecology,” he said. “The pope does talk about climate change, but it’s not the principal subject.

“In the long tradition of many papal messages, it’s a social encyclical, expanding on what Francis’ predecessors have said. Pope Paul VI defined peace in terms of development — not the technical or natural kind, but development of the whole person. (Pope) John Paul II expanded on this, saying concern for the poor, the aged, the jobless, the unborn all were integral to full human development.” he said.

“And (in his encyclical) ‘Caritas in Veritate,’ (Pope) Benedict XVI said that ‘when human ecology is respected within society, environmental ecology also benefits.'”

“The roots of ‘Laudato Si” are in the life and ministry of Pope Francis in Argentina, his relations with the poor of Buenos Aires and the popular movements of the ‘campesinos’ (peasant farmers). The pope wanted to plant a flag in the Vatican with the people of all nations fighting for access to land, work, and housing,” Cardinal Turkson said.

[hotblock2]

He told the audience that one way of summing up the encyclical’s message would be in what he called “the three Cs” — continuity with other popes’ messages; collegiality, referring to the encyclical’s quoting from documents about the environment by bishops’ conferences around the world; and care.

“Past papal documents have talked about ‘custody’ of the environment, but that word is used only twice in “Laudato Si’,” he said. “The rest of the time, it talks about ‘care.’ The first word means a stewardship that is neutral and dispassionate. ‘Care’ goes beyond that. It’s an ecological conversion that leads to an ecological citizenship and celebration of God’s gifts.

Cardinal Turkson first learned that the pope was considering an environmental encyclical in March 2014, just before the feast of St. Joseph, March 19. “That may not have been a coincidence,” he said. “Just as Joseph was the protector of Jesus, the pope invites us to be protectors of the environment and the world.”

On April 13, 2014, which was Palm Sunday, Pope Francis told the cardinal and the justice and peace council’s staff to start drafting the encyclical. “In the past, the pope would meet with the group working on an encyclical to discuss a basic draft,” Cardinal Turkson said. “I asked him at the Palm Sunday Mass, ‘When can we get together?’ His response was ‘No, you begin to write.'”

The drafting group consisted of the cardinal and about a half-dozen others, including one American, working on the entire document with a collaborative approach — and with “a lot of input from all sides, including the Peabody Coal Co. and oil drilling groups,” he said. The draft was done by June 18, 2014. Dated May 24, 2015, it was officially published June 18, 2015.

Cardinal Turkson said he was pleased with people’s overall response to the document, saying he expected and received a mixed reaction.

“One thing I have learned from what people in the United States have said is that some seem to equate Catholic social teaching with the political philosophy of socialism,” he said. “People who do this misunderstand. Catholic social teaching reflects the words in the Letter of James that ‘faith without works is dead.’

“All Catholic social teaching has its basis in Scripture and represents a dialogue between philosophy and social science. If the work ‘social’ is causing a problem, perhaps we need to find another word to make it more acceptable.”

***

Puet, is a reporter at the Catholic Times, newspaper of the Diocese of Columbus.

PREVIOUS: Diocesan money managers hear of parish turnarounds

NEXT: Ohio Catholic first woman to lead a national organization for veterans

Share this story