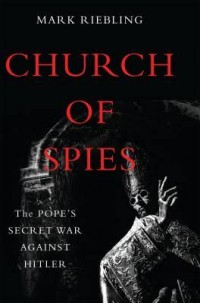

“Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler”

“Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler”

by Mark Riebling.

Basic Books (New York, 2015).

384 pp., $29.99.

Who really was Pope Pius XII during World War II? Was he a weak pope, too afraid to speak out publicly against Hitler? Or was he an expert diplomat, calculatingly using his position to help posture assassination attempts of the horrific German leader?

Author Mark Riebling’s book, “Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War against Hitler,” contends that the pontiff was indeed a skilled man who used his role to help German plotters attempt to kill Hitler. The book even suggests that his initiatives came at the cost of his legacy and reputation, a point of wide controversy for historians.

“Church of Spies” reads like a spy thriller that is exhaustingly researched, as shown by its more than 100 pages of notes and sources. Riebling, a former editor at Random House and author of “Wedge: The Secret War Between the FBI and CIA,” has researched and written about intelligence for various publications. He shares with readers many vivid details about the underground communication, secret meetings and failed attempts to take Hitler’s life; the book truly is a treasure trove of surprising information.

[hotblock]

“Church of Spies” reveals that the Pope Pius’ much-criticized public silence during World War II was in fact part of a cover for underground diplomacy, spy games and double agents. So ingrained was the pope in his secrecy during this time that he had an audio recording system built into the walls of the papal library.

A key player in the master plan for a peaceful Germany, the pope was part of a network of people pretending to be something they were not to help link the internal and external enemies of Hitler. Pope Pius’ code name during the operations was “chief,” a name the pope apparently liked.

The main character in the book is Josef Muller, known by friends as “Joey Ox” for his rural Bavarian roots and brunt determination to get things done. A Catholic lawyer, book publisher and general jack-of-all trades, Muller’s many hats made him a man who knew many and was owed many favors. His connections included Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Nazi secret military intelligence, and his deputy Hans Oster.

Though on the Nazi payroll, Canaris and Oster were spies working with conservative opponents of Hitler. The German intelligence agency was in fact the headquarters of the German military opposition to Hitler, and they needed Muller to make contact with the pope. Pope Pius’ rubber stamp of approval to plans gave the opposition the legitimacy needed for any real communication and cooperation between the German opposition and the Western powers.

To enable his trips back and forth to Rome, Muller acted somewhat as a triple agent. He spied for the Vatican while sharing information with Oster while pretending to spy on the Italians for the Nazis. In exchange for the life-threatening risks Muller took, he was married at the Vatican and was remembered in the pope’s daily prayers.

Pope Pius was a skilled leader of the church driven to politics by his nature and foreign affairs experience as then-Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli. Distrustful of Hitler from the beginning, he was not prompted to act until Hitler’s surge into Catholic Poland. Interestingly, Riebling notes, “The last day during the war when Pius publicly said the word ‘Jew’ is also, in fact, the first day history can document his choice to help kill Adolf Hitler.”

The book shows that Pope Pius put his reputation, safety and security on the line for peace. And although plots to remove Hitler failed, the Vatican’s secret connections helped changed the course of the war in several ways that indeed saved lives.

***

Lordan has master’s degrees in education and political science and is a former assistant international editor of Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: For Her aims to help women have life of ‘beauty, meaning’

NEXT: McCarthy stumbles to show who’s ‘The Boss’

Share this story