PORTLAND, Ore. (CNS) — An out-of-the way hilltop in rural Oregon is home to one of the West’s best collections of medieval and early Renaissance books.

The ancient tomes — overflowing with calligraphy, color and shining illumination made by hand in a different era — are worth millions of dollars. But no one at Mount Angel Abbey in nearby St. Benedict is counting riches. What matters to the monks is a legacy of faith and culture.

“Monasticism and books go together like macaroni and cheese,” says Benedictine Brother Christopher Walch, a 30-year-old novice monk from southern Oregon. “The two are good alone, but not as good as they are together.”

[hotblock]

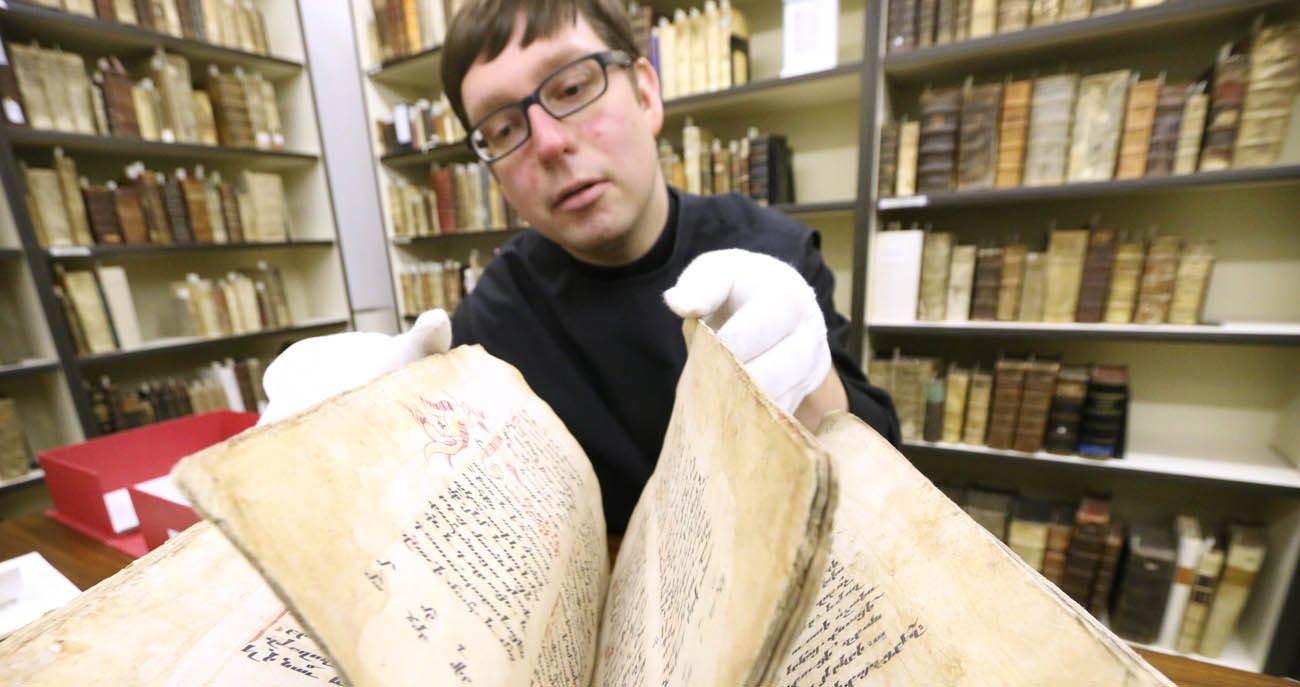

Brother Walch, who has shown interest in the library and its rare books, is being trained in the craft of book preservation.

The collection should not be a big surprise because monasteries have long been producers and preservers of culture, particularly the written word. Monks read and pray from books and even hear from a book while they are eating.

Brother Walch thinks of the library as the monks’ communal preaching.

“Books have been monks’ way to engage the world,” he says. “We create a library and say, ‘This is what we think is important. You are welcome to use it.'”

Victoria Ertelt, library administrator, also is excited about sharing the beauty of the medieval works. “In the first place, it’s really amazing that we have this sizable collection of rare books in this small little abbey in rural Oregon,” she told the Catholic Sentinel, Portland’s archdiocesan newspaper.

The Benedictines have a history of appreciation for older books. Some of the original monks brought books from their mother abbey, Engelberg in Switzerland, when they settled in Oregon in 1882. Over the years, other books have been acquired. There is a 13th-century Bible printed on parchment — treated animal skin — that looks much like it did 800 years ago.

[hotblock2]

In the 1930s, Father Martin Pollard, studying in Rome at the time, came upon a closing bookstore in Aachen, Germany, that specialized in theology, history, and the sciences. For $785, the owner sold the abbey 15,000 books, the oldest from 1519. This purchase helped rebuild a library that had been lost in a fire in 1926.

Over the decades, the abbey has added to its collection, hoping to preserve rare manuscripts. In the 1980s, the monks sent several of their rare books to Reed College for an exhibit. Following that event, a family who had also contributed to the display decided to donate a dozen of their books to the abbey for safekeeping and preservation.

The abbey’s rare books are being shown in a modern way. Stephen Delamarter, professor at George Fox University in Newberg, Oregon, supervised students who digitized the collection. Ertelt says digitization will help preserve the books because they will not need to be handled by researchers.

The books have been shared in recent exhibits at the Oregon Jewish Museum and the Multnomah County Central Library.

An art historian from the Getty Museum came to examine them; she is working on a doctorate in medieval manuscript repair.

For decades, the abbey’s books were distributed here and there, in attics and basements. By the 1960s, Father Barnabas Reasoner suggested a central library. Other monks stepped in to sustain and improve the collection.

Now, the library has 370,000 books in general circulation and thousands of rare volumes. The most important books are kept in a vault with a thick steel door.

In the medieval period, more laypeople wanted to pray like monks. Modified books of psalms and prayers, called “books of hours,” became best-sellers. Even the middle classes bought them, though the more expensive the book, the more plentiful and fine the illustrations. It’s likely that women used books of hours the most because men spent the day working.

Medieval bookmakers assumed owners would write in the margins, making the book their own. That’s why margins from the era are so wide.

Illustrators at times included inscrutable inside jokes. One page from a book of hours in the Mount Angel collection shows a monkey in papal tiara ordaining another monkey.

***

Langlois is editor of, and Ethen is a freelance writer for, the Catholic Sentinel, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Portland.

PREVIOUS: Student says religious icons are ‘transitions, windows into spirituality’

NEXT: When Harry ‘met’ Harry, years apart, under a New Orleans bridge

Share this story