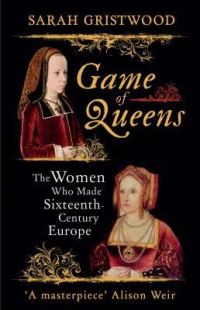

“Game of Queens: The Women Who Made Sixteenth-Century Europe”

“Game of Queens: The Women Who Made Sixteenth-Century Europe”

by Sarah Gristwood.

Basic Books (New York, 2016).

351 pp., $28.99.

European history between the years 1474, when Isabella became the regnant of Castile (in what is now Spain), until the death of the English queen Elizabeth Tudor in 1603 is a remarkable era for many reasons, one of which is the number of women — 16 in total — who played significant roles in ruling their respective countries either as queens in their own right or as queen mothers or regents. The story of the role these women played in history is delightfully told by Sarah Gristwood in her book “Game of Queens.”

In France, where the law prevented women from inheriting thrones, women could not rule in their own names or by their own authority. While law did not prevent this in other countries, custom called for thrones to pass to the oldest surviving son or male next of kin. This period of 110 years saw more women occupy thrones than ever before.

As Gristwood notes, prior to Isabella’s reign all pieces on the chess board were male. The queen, with her almost unlimited ability to act, was added in Spain during her reign and spread throughout Europe. Just as adding the powerful queen to the game changed chess, Gristwood suggests, adding powerful women to political rule changed the world.

[hotblock]

One of the most difficult challenges to telling the history of this period — whether history in general or the role of women in it — is keeping track of the names, countries and dates of the characters. This is especially complicated by the fact that the ruling families of Europe intermingled incessantly to create alliances, for example Katherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry VIII linking the English and Spanish thrones. Add to this mix the popularity of the names Mary (Maria) and Margaret — 8 of the 16 women were so named — makes for confusion. Although Gristwood provides dynastic charts, a “dramatis personae” — a list of significant actors — and a chronology, keeping track of who’s who remains a challenge.

The style of type used in this book is confusing. For example, Gristwood uses asterisks within the text to indicate her many informative footnotes. Unfortunately, the asterisks are so small that they are difficult to find, even when one searches the page diligently for them.

Another type problem is that single quotation marks are used for quotes, not double marks, which takes a while to recognize automatically. One additional disappointment is that while the book is filled with helpful quotations taken from the letters of the period, they are not footnoted. Gristwood does provide helpful information in this matter at the end of the book in the Notes and Further Reading section, but this information would have been more helpful if noted at the time.

Those problems aside, this book is well written and the chapters are short and well organized. The story told here does justice to the lives and memories of the women who broke the European glass ceiling so many years ago.

***

Mulhall lives in Louisville, Kentucky.

PREVIOUS: CRS unveils book about Muslim-Christian cooperation in peacebuilding

NEXT: ‘LA 92,’ 9-11 p.m. EDT, April 30, National Geographic channel

Share this story