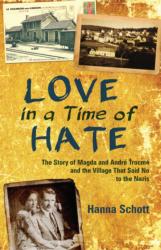

“Love in a Time of Hate: The Story of Magda and Andrew Trocme and the Village That Said No to the Nazis”

“Love in a Time of Hate: The Story of Magda and Andrew Trocme and the Village That Said No to the Nazis”

by Hanna Schott; translated by John D. Roth.

Herald Press (Harrisonburg, Virginia, 2017).

269 pp., $16.99.

One wintry evening in 1940 the doorbell rang at the home of Magda and Pastor Andre Trocme in the not-yet-famous town of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, France. Opening the door, Magda saw a German Jewish woman shivering in the cold. Someone had informed her that the small town’s Reformed Church pastor and his wife could help her.

In October 1940 “an order came into effect for all of France … that all Jews were to be handed over to German officials,” writes Hanna Schott, author of “Love in a Time of Hate.” Immediately “Jews from throughout the whole country were in transit,” searching “for safe places to stay.”

That is what the Trocmes’ home, along with homes of nearby villagers and local farmers, would become, and the reason history remembers Le Chambon. It served during World War II as a place of welcome for Jews fleeing the Nazis’ murderous persecution.

[hotblock]

“Love in a Time of Hate” tells the story of the Trocmes and others in Le Chambon who courageously and cleverly put their faith into action to hide Jews. Many in Le Chambon accepted it as their responsibility “not only to do good, but also to prevent evil from happening.”

The book accompanies the Trocmes from their courtship’s first days to the last days of their old age. They married in 1926. Andre came over time to grasp “the extraordinary love and commitment of which Magda was capable,” he once wrote.

It appears that the Trocmes’ profound integrity and respect for others demanded that they put their faith into action by standing uncompromisingly at the side of those they welcomed to their home and town.

“We don’t know what a Jew is. We only know human beings,” Andre, at great risk to himself, boldly informed the provincial governor in 1942.

Andre described in a 1958 letter the underlying conviction that had motivated his actions. In his mid-30s he made “a great discovery,” namely that “every other person existed just as (he) did, was just as unique and important as (himself).”

He then knew, he explained, “what love meant: to regard another person as you regard yourself; to actually put yourself into their situation instead of just dreaming that you love them.” The “truth of God,” he wrote, is “the other: the other human, the Jew, whom one hides.”

In this pastor the Reformed Church had not only someone of astonishing commitment, but a pacifist too, whose distaste for war and killing was rooted in convictions that arose in his earliest teen years during World War I.

With close relatives living in Germany, the devastating realities of war disturbed Andre. He wondered what he would do “if someday he encountered his cousin Wilhelm … wearing the uniform of a German soldier.”

In one of many vivid stories that make this book so readable, “Love in a Time of Hate” describes a conversation during World War I when the youthful Andre encountered one of the German soldiers occupying his family’s home in Saint-Quentin, France.

The soldier offered Andre a piece of bread. “I don’t accept any bread from an enemy,” Andre told him. But the soldier responded, “I’m not the kind of person you think.”

The soldier was a Christian, a pacifist and carried no weapons. Andre for the first time “encountered a man who refused military service for reasons of conscience.”

The Jews sheltered in Le Chambon during World War II included many children. A number of them resided in the Tante Soly Hotel on the main street. It was a “curious neighborhood,” Schott says. Right next door was a house occupied by German soldiers.

A little story in this book recalls a step frequently taken to protect this “neighborhood’s” children. Schott writes that “whenever it seemed that a raid was imminent, the Tante Soly innkeeper sent the children out the rear entrance and from there … into the woods to ‘hunt for mushrooms.'”

In the days of World War II, a biblical passage from the Book of Numbers fascinated Andre with its suggestion that a town might serve as a place of refuge, a necessary safe haven (Chapter 25, Verses 11-15). This inspired him to hope that Le Chambon could become just such a place.

***

Also of interest: “The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945” by Guillaume Zeller. Ignatius Press (San Francisco, 2017). 280 pp., $16.95.

***

Gibson was the founding editor of Origins, Catholic News Service’s documentary service. He retired in 2007 after holding that post for 36 years.

PREVIOUS: ‘Daughters of Destiny’ shows how to lift India’s ‘untouchables’ one child at a time

NEXT: In ‘Logan Lucky,’ think ‘Ocean’s Eleven’ with a backwoods twang

Share this story