VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Secret negotiations between Heinrich Himmler — the “architect” of the Holocaust — and a Swiss Catholic politician, hired by a Jewish woman and helped by an Italian papal nuncio, may have contributed to ending the mass extermination of the Jewish people, according to a Canadian researcher.

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Secret negotiations between Heinrich Himmler — the “architect” of the Holocaust — and a Swiss Catholic politician, hired by a Jewish woman and helped by an Italian papal nuncio, may have contributed to ending the mass extermination of the Jewish people, according to a Canadian researcher.

The general view of most historians is that the Nazis destroyed the death camps to hide the evidence of the millions of people they slaughtered.

But Max Wallace, a Canadian historian, author and filmmaker, believes there is more to the story.

The author also hopes that the full opening of the Vatican archives from that period could shed more light on all the reasons Himmler gave orders to end the systematic slaughter of the Jews in the fall of 1944, many months before the Nazis surrendered to the Allies in May 1945. More specifically, eyewitnesses reported Himmler gave orders to blow up the gas chambers and crematoria of Auschwitz-Birkenau two months before Joseph Stalin’s Red Army stormed the camp gates in January 1945.

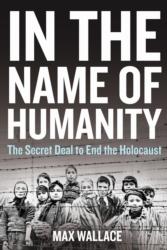

The reasons for Himmler’s directives “may very well rewrite the history of the Holocaust,” Wallace wrote in a new book, “In the Name of Humanity. The Secret Deal to End the Holocaust.” The author gave Catholic News Service an advance copy of the book, which is being released by Penguin/Random House Canada Aug. 22 and worldwide in the spring of 2018.

[hotblock]

The book is based on the insights of other Holocaust historians and more than 15 years of Wallace’s own research — sifting through thousands of documents in archives around the world, he told Catholic News Service in an interview in July.

Much of the book focuses on the work of Recha and Isaac Sternbuch, the Switzerland-based representatives of Vaad ha-Hatzalah, a rescue committee formed by the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada in 1939 to promote and actively take part in the rescue of Europe’s Jews.

Recha Sternbuch arranged for the rescue of thousands of Jews and she sent important information around the world about their plight using her connections with the Polish and Vatican embassies in Switzerland and the access they gave her to their couriers.

She worked closely with the Vatican nuncio in Bern, Archbishop Filippo Bernardini, who “was very involved with rescue efforts and support,” Wallace said.

It was the archbishop, he said, who introduced Sternbuch to Jean-Marie Musy, a Fascist and fiercely anti-Bolshevik, devout Catholic and former president of Switzerland, whose father-in-law had been a Swiss Guard and a “papal count,” giving him a close connection to the Vatican.

Because Musy knew Himmler and could have great influence over him, Wallace said, Sternbuch quickly enlisted Musy’s help negotiating with the Nazis on the group’s behalf to save the Jews.

Based on evidence gleaned from archives and recorded testimonies, Wallace details the secret deals, bribes and false promises Musy and others used to manipulate Himmler over the course of several months, “exploiting his desperate desire for a separate peace with the Western Allies.”

“Musy and the Sternbuchs exploited this delusion by convincing him that such an alliance (with the Allies) was only possible if he ended the extermination of the Jews,” Wallace said.

The “first significant deal” with the Germans involved freeing Jews in exchange for tractors, a deal that started taking concrete shape in November 1944, he said.

The Germans promised that once the deliveries of tractors began seriously, they would “blow up the facilities at Auschwitz,” Wallace said, citing archival evidence.

A cable dated Nov. 20, 1944, from Sternbuch to the Vaad in New York, says, Musy, “our delegate,” had returned from Berlin with a proposal “for a gradual evacuation of Jews from Germany.”

“In interim secured promise to cease extermination in concentration camps,” the cable reads. “On basis of intervention by nunciature in Bern the German government confirmed this promise to the Vatican.”

Another cable from Sternbuch to the Vaad dated Nov. 22, confirmed that the papal nuncio in Bern “received promise slaughters will cease.”

Three days later, Himmler issued orders to stop the further mass killings of Jews and to destroy the gas chambers and crematoria at Auschwitz; for Wallace, that may not be a coincidence, but may be linked to the negotiations.

The Nazis destroyed death camps to hide the evidence of their heinous crimes, but that usually was done right before Allied forces closed in, Wallace said; the Soviets were still at least another two months away when the extermination apparatus at Auschwitz was dynamited, and the Nazis left behind there more than 7,000 detainees, who would be crucial eyewitnesses.

While the Holocaust claimed as many as 11 million lives, “the Nazis could have killed all the remaining Jews,” especially as they were losing the war, but negotiators tricked Himmler into preventing the continued slaughter, Wallace said.

“That’s why there are survivors,” he said, estimating that as many as 300,000 Jews may have been saved in efforts linked to the secret negotiations.

While Wallace said there has “never been smoking gun evidence definitely proving Himmler’s motive,” he believes more details or insight might be found in the Vatican Secret Archives.

Documents of Pope Pius XII’s pontificate from 1939 to 1958 have not been opened to scholars, although the Vatican has said for years that it was making the necessary preparations to open them.

A source told CNS in July the preparations have been completed and the archives likely will be opened in 2018. However, Pope Francis must approve the opening and set the date.

Even though Wallace’s book does not focus on the Vatican’s work during the war, he said that with his extensive research, “I saw the efforts of the church behind the scenes and how they were incredibly influential,” especially in saving the remaining Jews in Hungary. “I gained a lot of respect for the Vatican and the church,” said Wallace, who was raised Jewish.

[hotblock2]

Jesuit Father Gerald Fogarty, an expert in Vatican-American relations, who is completing a book on the United States and the Vatican during World War II, said the nuncio, Archbishop Bernardini, is an important figure in history, but there is little documentation about the role he played during the war.

The U.S. priest said he scoured archives wherever the archbishop lived: in Switzerland; Australia; and Washington, D.C., where he taught canon law at The Catholic University of America and was adviser to the apostolic delegation in Washington for 25 years.

Being posted in a neutral country meant Archbishop Bernardini had regular contact with representatives of the Axis powers and Allied nations, giving him not only access to important information, but also the possibility of relaying messages between the two powers, according to archival research Father Fogarty sent to CNS.

The Vatican’s policy was and continues to be “impartiality, not neutrality,” which means “working both sides” in world affairs, the Jesuit said.

The eventual opening of the Vatican’s archives for the World War II period, he added, will be extremely helpful for researchers.

PREVIOUS: ‘Blood flowing on sidewalks’: 2 Philippine prelates criticize drug war

NEXT: Chicago youth travel to Salvador, bring back ideas for dealing with gangs

Share this story