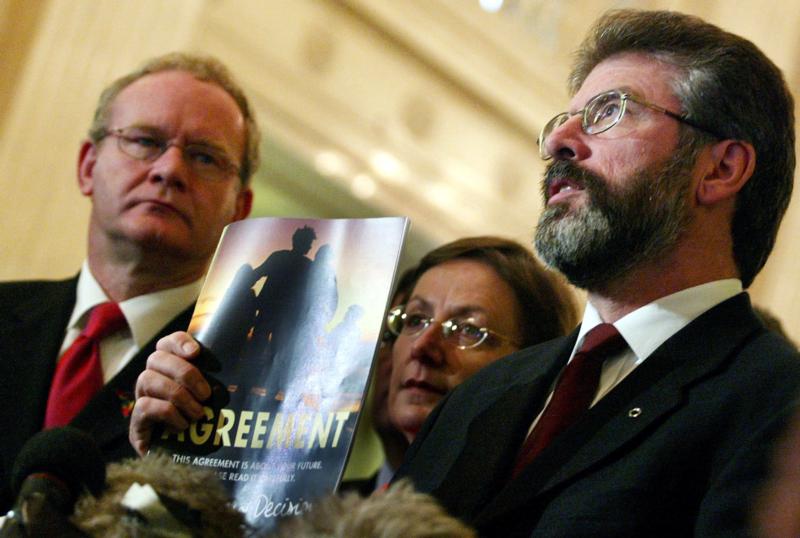

Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams, right, holds a copy of the Good Friday Agreement with Martin McGuinness, left, as they speak to journalists in the Stormont parliament building in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Oct. 14, 2002. The 20th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement should be a time of celebration, but Irish church leaders say Brexit raises fears of a return to a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. (CNS photo/Darren Staples, Reuters)

DUBLIN (CNS) — April 10 marks the 20th anniversary of the historic Good Friday Agreement, which brought peace to Northern Ireland. The peace deal effectively brought an end to “The Troubles,” which had cast a sectarian shadow over Northern Ireland for three decades and resulted in the deaths of more than 3,500, the majority of whom were civilians.

The Agreement saw the removal of British Army security checkpoints and watchtowers along the 310-mile border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, making cross-border travel much more accessible and increasing trade.

But today, at least one Irish bishop is concerned that the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union could complicate life for Ireland, north and south of the border. Despite assurances from London, Brexit has raised fears of a return to a hard border on the island of Ireland with the specter of customs posts between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. In some cases, farms, businesses and even some homes straddle the border, and what the future holds for them remains unclear.

[hotblock]

Britain and Ireland’s shared membership of the European Union meant Brussels became the source of much-needed funding for cross-border cooperation programs aimed at helping trade. But in the wake of the Good Friday Agreement, these programs also eased tensions between divided and alienated communities. Ireland and the U.K. are currently partners in three EU-funded cross-border cooperation programs worth about $800 million.

“The Good Friday Agreement was based on the assumption that both the Republic of Ireland and the U.K. would be in the EU together,” Bishop Donal McKeown of Derry told Catholic News Service.

The bishop said the prospect of a hard border would cause “enormous resentment. It would mean going back on the ‘identity’ assumptions of the Good Friday Agreement. There is also resentment in some quarters that English nationalism has decided to leave the EU and that Northern Ireland and Scotland (which both voted to remain within the EU) simply have to follow mother.”

Overall, 55.8 percent of the people of Northern Ireland voted to remain in the E.U. But as part of the U.K., Northern Ireland still must leave, and it will thus lose EU subsidies worth 87 percent of all farm earnings.

Officials estimate at least 30,000 people currently cross the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland every day for work, an indication of how interconnected their economies have become.

Brexit is causing “huge concern,” Bishop McKeown acknowledged. On the economic front, the economies of Northern Ireland and the Republic “are intertwined, most especially in the field of agriculture and food production/processing. Within the EU, the two jurisdictions have been enabled to grow together with enormous benefits for both.”

Although the six counties of Northern Ireland are part of the United Kingdom, the Irish church is united on the island. Bishop McKeown’s own Diocese of Derry is one of three dioceses that straddle the Ireland-Northern Ireland border. The others are Armagh and Clogher, and the Diocese of Kilmore has half a parish in Northern Ireland.

[tower]

“We already have to deal with two currencies, two legal jurisdictions, and two education systems,” Bishop McKeown explained.

But that situation could become even more complicated in the wake of Brexit if customs tariffs are introduced.

“A hard customs border will be hugely damaging to businesses on both sides of the border, where unhampered travel currently is taken as normal,” the bishop said.

He recalled how 100 years ago, before the partition of Ireland, Belfast was the third industrial city of the U.K. “After partition, Belfast and Northern Ireland gradually became a backwater. Because Northern Ireland is so small, it needs to be part of an all-Ireland economy,” he suggested.

In January 2017, the power-sharing government in Belfast collapsed over a row between the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Fein, the two main parties representing the still-polarized community. The impasse prompted Owen Paterson, a conservative member of the British Parliament, to tweet, “The collapse of power-sharing in Northern Ireland shows the Good Friday Agreement has outlived its use.”

But in a recent op-ed for the Guardian newspaper, Irish Deputy Prime Minister Simon Coveney described the 1998 peace deal as “perhaps the greatest U.K.-Ireland achievement of recent times.”

He said the Irish government was determined to ensure that the agreement, which “removed barriers and borders — both physically, on the island of Ireland; and emotionally, between communities in Ireland and between our two islands,” would not suffer because of Brexit.

PREVIOUS: New life budding in Iraq but challenges remain, CRS says

NEXT: Caritas: More poverty among young Europeans leads to hopelessness

Share this story