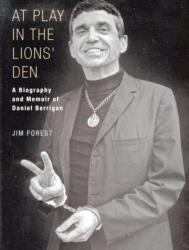

“At Play in the Lions’ Den: A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan”

“At Play in the Lions’ Den: A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan”

by Jim Forest.

Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York, 2017).

352 pp., $28.

Jim Forest has given us an extraordinary biography and memoir of Father Dan Berrigan (1921-2016), the Jesuit priest, poet and peace activist who sometimes went to jail for his convictions.

Forest, who often joined Father Berrigan in his peacemaking activities, shares intimate and wide-ranging insights about a friendship that spanned more than five decades. If you are going to read just one biography of this remarkable man, this account is a standout.

“Daniel in the lions’ den was a particular scene in Romanesque stone carving, a visual anticipation of Christ’s death and resurrection,” Forest writes. He tell us that “Dan Berrigan spent much of his life in various lions’ dens — at home as a child when his father was in a rage, in paddy wagons and prisons, in demonstrations that were targets of violent attack, in a city under bombardment (when he visited North Vietnam in 1968 to free jailed U.S. pilots), in urban areas police would describe as hazardous, yet remarkably he lived to be 94, dying peacefully in bed, though he had many invisible scars and scratches.”

[hotblock]

Father Berrigan was born to a devout Catholic family near Virginia, Minnesota, on the Mesabi Iron Range. His beloved mother, Frida, was an immigrant from Germany’s Black Forest region, and his paternal grandfather had emigrated from County Tipperary. His father, Thomas, born in America in 1879, was a harsh disciplinarian, a union member and an unpublished poet who helped found a local chapter of the Catholic Interracial Council. He subscribed to The Catholic Worker, Dorothy Day’s monthly tabloid that embraced social justice and peace — and for which Forest served as managing editor in the early 1960s.

Perhaps not so surprisingly, three of the six Berrigan sons became priests, although Jerry and Phil later left to marry and have families. But Dan remained a lifelong stalwart Jesuit, although he sometimes criticized the failure of the order — and of the church — to fully live up to Catholic teachings.

Forest recounts how, when he once asked Father Berrigan why he joined the Jesuits, the priest explained that “it was their bare-bones undersell.” While other religious orders advertised in “glossy brochures … photos of pretty buildings, swimming pools, rec rooms and basketball courts,” the Jesuits’ promotional material consisted of the opposite — a very plain folder, no photos and an austere text that featured “some tough quotations from St. Ignatius Loyola! The real thing. No icing.”

In 1967 Father Berrigan became the first American Catholic priest to go to jail for anti-war civil disobedience after he joined 100 students from Cornell University (where he was a chaplain) to protest at the Pentagon. His brother Phil became the second. The following year the two brother priests joined seven other Catholic activists to burn draft records in the parking lot of the draft board in Catonsville, Maryland, for which they received jail time.

Rather than destroy the draft records clandestinely at night, the Catonsville Nine deliberately chose to do so publicly in daylight. Forest explains that their purpose was “not only to destroy papers but to take personal responsibility for what they had done and then to put the war on trial.”

While initially many prominent Catholics such as the novelist Walker Percy disapproved of the action, Father Berrigan found support from his two mentors, Dorothy Day and the Trappist monk, Father Thomas Merton. However, both took issue with the methods used; Day for her part cautioned against such property destruction’s potential to lead to violence.

Forest notes that two decades later Father Berrigan observed in his autobiography that “the act was pitiful, a tiny flare amid the consuming fires of war. But Catonsville was like a firebreak. … (it) seemed to light up the dark places of the heart, where courage and risk and hope were awaiting a signal, a dawn.”

[tower]

Catonsville was just one of many anti-war demonstrations that Father Berrigan took part in, often with his brother Phil. Over the years, he poured blood at the Pentagon to protest the arms race, and was arrested for civil disobedience there, at the United Nations, and at assorted arms manufacturers.

In 1980, Father Berrigan was arrested with eight others at the GE Missile Plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, and again served jail time. His last arrest, shortly before he turned 90, occurred in April 2011 aboard the USS Intrepid war museum in New York. In his later years, he also cared for AIDS sufferers and dying hospice patients.

Forest’s engagingly written account brims with insights into Father Berrigan’s character.

For instance, the priest held strong convictions but was not self-righteous. “One of the things Dan showed me was that you don’t have to wag a scolding finger at others in the effort to live and advocate a peaceful life.” Even when others held diametrically opposing views, “in face-to-face encounters he had an amazing gift to make space for and welcome the other, to tell stories and jokes, to create bridges of affinity and laughter.”

This is just one of many valuable revelations that Forest’s decades-long friendship and collaboration with Father Berrigan enable him to share. Yet the book is no hagiography, but a rich, multi-tapestried account of this passionate modern-day prophet and activist.

“Dan was easy to love but even late in life he could be a challenging person to be with,” Forest discloses. “While he wasn’t a recruiting sergeant, he made clear to all who encountered him that the possibility exists to reshape one’s life around the beatitude of peacemaking: ‘Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called children of God.'”

Forest acknowledges that “Dan helped me imagine taking a step — burning draft records in Milwaukee in 1968 — that I might not otherwise have taken. While I still have troubled feelings about the year my 7-year-old son, Benedict, and I lived apart from each other, it nonetheless gives me pride to have been one of those who put war resistance above personal freedom. Thank you, Dan, for nudging me over the cliff of my own fears.”

Forest, 76, a longtime peace activist, has written numerous critically acclaimed books, including “Living with Wisdom: A Biography of Thomas Merton” and “All Is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day.” He is the international secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship.

Scrupulously researched, with detailed notes, “At Play in the Lions’ Den” includes many insights as well about Phil Berrigan and his relationship with his brother Dan. For many years, the two were partners in their activism against war and racism; both marched in Selma in 1965 with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., for example.

The book also includes a detailed chronology of Father Berrigan’s life and work in an appendix. Scores of well-chosen photographs depict every stage of his life and enrich the text to create an authentic record of this complex and inspiring life lived true to heartfelt convictions.

***

Roberts directs the journalism program at the University at Albany, State University of New York, and has written two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.

PREVIOUS: Shark adventure ‘The Meg’ bites with tongue in cheek

NEXT: ‘Dog Days’ sniffs out tales of owners’ lives and loves

Long live the memory of the heroic life of Fr Dan Berrigan.

An error-Brother Jerome Berrigan, while a Josephite seminarian for a time, was never ordained.