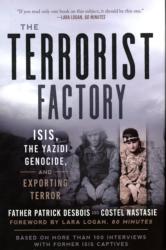

“The Terrorist Factory: ISIS, the Yazidi Genocide and Exporting Terrorism”

“The Terrorist Factory: ISIS, the Yazidi Genocide and Exporting Terrorism”

by Father Patrick Desbois and Costel Nastasie.

Arcade Publishing (New York, 2018).

197 pp. $24.99.

The atrocities of the Islamic State (IS) are manifold. While trying to form an Islamic caliphate in parts of Iraq and Syria, IS activities have included genocide, religious persecution, sexual slavery, the brainwashing of teen prisoners, forced conversions and training teens in the savagery of warfare and terrorism. Although the caliphate is disappearing, its scars remain.

“The Terrorist Factory” recounts the individual human tragedies caught up in this terrorist organization. The authors and their investigative team dive into the murky waters of caliphate atrocities to put human faces on IS victims. The focus is on the Yazidi, a non-Muslim ethnic minority native to the region, singled out by IS for extermination.

Based on interviews during 2015-16 with over 100 Yazidis who escaped from IS capture and found their ways to refugee camps in Iraq, the book refutes IS claims of trying to establish a country based on a morally grounded form of Islam. Instead, the authors argue, the group’s real aim is to subjugate people for the benefit of a privileged few. “Sex, money and power” form “the three pillars of the Islamic state,” they conclude. “(IS’s) radical Islam, like Nazism, in no way elevates the human spirit, contrary to its claims.”

[hotblock]

Both authors are qualified to make such pointed judgments, as they have investigated other efforts to eliminate large swaths of humanity by groups claiming superiority over others. Father Patrick Desbois, a French Catholic priest, has written books on the Holocaust of Jews killed by the Nazis in German-occupied Eastern Europe and the then-Soviet Union during World War II. Costel Nastasie, a native of Romania, has conducted extensive research on the persecutions and mass murders of the Roma, also known as gypsies.

The book’s title comes from the firsthand descriptions given of the training received by recruits and teen captives coming from different countries. Indoctrination and brainwashing tactics forced captives to convert, with beatings reserved for those reluctant to join in prayer. The training included use of sophisticated automatic weapons and the making of roadside bombs and suicide belts to be strapped on “martyrs.” Some were to become soldiers used to capture territory or defend it from enemies. Others were to be chosen for suicide missions.

Girls became sex slaves. The promise of sex on demand is an important recruiting tool, according to the authors. The girls are either sold to an IS leader or a moneyed member, or placed in brothels where they are raped by rank-and-file members lacking economic means. Many times the girls are resold once the IS member becomes tired of them. Besides being subjected to sex on demand, many of the girls interviewed recount how they were also mistreated by the wives of their owners, and sometimes beaten with wire cables.

Sex slaves of important IS leaders also became part of the war effort. One interviewee tells how she traveled with her owner, was taught to make bombs and suicide belts and had to strap a belt around herself in case she was in danger of capture.

The interviewing process itself was trying on the authors beyond the horror stories. Much of the fieldwork was done in 120-degree desert heat and in cramped refugee trailers often housing a dozen people. Also, the writers were troubled because they would return in air-conditioned vehicles to hotel rooms while the refugees remained in substandard conditions.

On a larger plane, the book poses the question: Why throughout history do such atrocities, fueled by hatred and violence, continue in some spots of the world, while in others people in comfort do little to prevent it?

***

Bono is a retired CNS staff writer.

PREVIOUS: ‘Holmes & Watson’ is all too elementary

NEXT: Historian provides riveting account of WWII chaplains from Notre Dame

Share this story