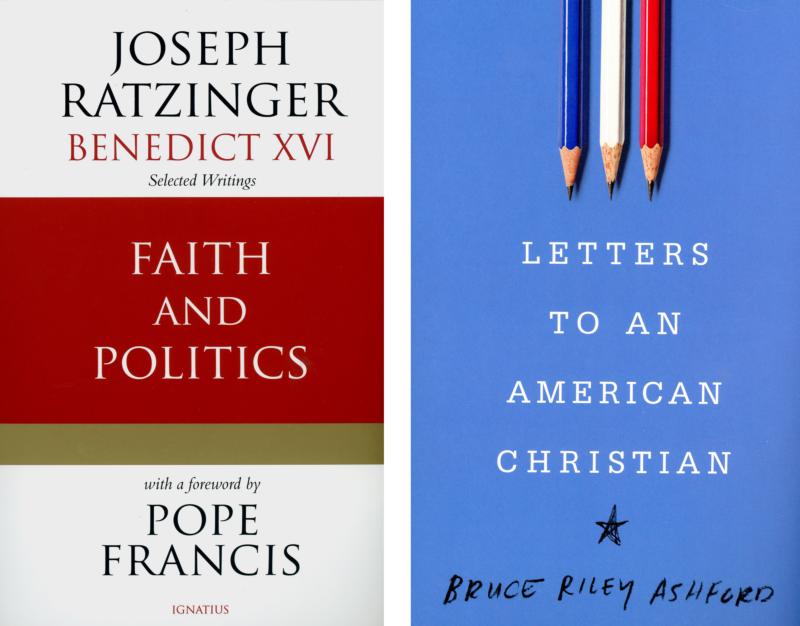

These are the covers of “Faith and Politics: Selected Writings” by Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI; translated by Michael J. Miller and others, and “Letters to an American Christian,” by Bruce Riley Ashford. The books are reviewed by David Gibson. (CNS)

“Faith and Politics: Selected Writings”

by Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI;

translated by Michael J. Miller and others.

Ignatius Press (San Francisco, 2018).

269 pp. $18.95.

“Letters to an American Christian,”

by Bruce Riley Ashford.

B&H Publishing Group (Nashville, Tennessee, 2018).

239 pp. $16.99.

What relationship is possible between the realms of faith and politics, key dimensions of life that, to be clear, some believe are so unalike as to be opposed? The question is one of endless fascination for Christians aiming to live with integrity and contribute effectively to the life of their confounding societies.

Christians tend to agree broadly today that valuable roles await them in political matters, which so greatly affect all citizens’ lives. Yet the chaos and antagonism common in the universe of the political turn many away.

[hotblock]

It is essential, however, to work “to transform the world, soberly, realistically, patiently, humanely,” retired Pope Benedict XVI says in “Faith and Politics,” a 2018 collection of writings that demonstrate his lifelong interest in this topic. He emphasizes, though, that humanity “has a demand and a question that go beyond anything politics … can provide.”

Certainly, there is work for Christians to do in the political realm, work encompassing local, national or international concerns.

Another 2018 book underscoring Christian concerns in the political sphere is “Letters to an American Christian” by Bruce Riley Ashford, provost and a professor of theology and culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina.

Speaking about “the enduring (albeit complicated) good of politics,” he writes: “Although human sin inevitably twists and corrupts human political efforts, we as Christians should allow our Christian faith to help untwist what has been twisted and bring healing to the corruption.”

Each of Ashford’s 26 brief letters addresses a student his book calls Christian. The author tries “to help (Christians) construct a political paradigm that recognizes God’s sovereignty over our nation, draws on our Christianity to work for the common good, and respects the dignity and rights of citizens who have differing visions of the common good.”

These books by Pope Benedict and Ashford illustrate contrasting ways of approaching the relationship of faith and politics. One approach highlights the underlying convictions and theological, philosophical and social considerations that commonly shape Christian thinking here. The other accents the so-called “hot-button” issues dominating political discourse at any given moment.

[tower]

It seems virtually impossible to adopt one approach to the other’s exclusion. For Christian political action always calls basic faith convictions into play, and politics always is about “something.” It is possible, though, to devote greater attention to one approach than the other.

Unsurprisingly, Pope Benedict aims to clarify underlying principles basic to Christian action in the political realm. “‘Bearing witness to the truth’ means giving priority to God and to his will over against the interests of the world and its powers,” he observes in discussing truth’s central importance.

Truth, he believes, “becomes recognizable when God becomes recognizable.” He warns that if truth is not recognized, a “rule of pragmatism is imposed, by which the strong arm of the powerful becomes the god of this world.”

None of this is to suggest that concrete issues of the day are somehow unimportant to Benedict XVI. Social justice, abortion, poverty and human dignity never are far from his mind. Consider these pointed comments made in discussing Christ’s real presence in the Eucharist:

It is necessary to learn, “not just theoretically, but in the way we think and act — that in addition to the real presence of Jesus … in the blessed sacrament, there is that other, second real presence of Jesus in the least of our brethren.”

Ashford devotes his book’s second part to “A Christian View on Hot-Button Issues.” But this does not mean he avoids basic principles that anchor Christian political thinking.

His book deals, he explains, “with the interface of religion and politics in general or religion and hot-button policy issues in specific.” Many readers will welcome his discussions of issues such as racism, nationalism, gun legislation, abortion, the environment, political correctness, immigration or civility, since such issues assume so prominent a place in today’s news.

Civility, Ashford explains, “includes listening to our opponents’ arguments not merely to counter them but also to understand.” Civility is “the ability to resist our worst impulses” and “live peaceably” with others.

Ashford cuts to the chase by adding: “Anyone can fly into a rage. It takes true strength to be slow to anger.”

In society’s current age of polarization, faith and politics may be a uniquely important topic. Perhaps these books can enable readers to consider thoughtfully what they want to achieve in the political universe and how.

“Politics should be done out of a desire for the common good,” Ashford says. It should manifest “our love for our neighbors.”

In a not dissimilar vein, Pope Benedict advises readers that “there is no antithesis between hope for heaven and loyalty to the earth.” Christians, he insists, “must bring hope into that which is transitory, into the world of our states.”

***

Gibson was the founding editor of Origins, Catholic News Service’s documentary service. He retired in 2007 after holding that post for 36 years.

PREVIOUS: ‘Jesus: His Life’ recreates and reflects on Gospels

NEXT: Looking to Easter, poems of life, death and what follows

Share this story