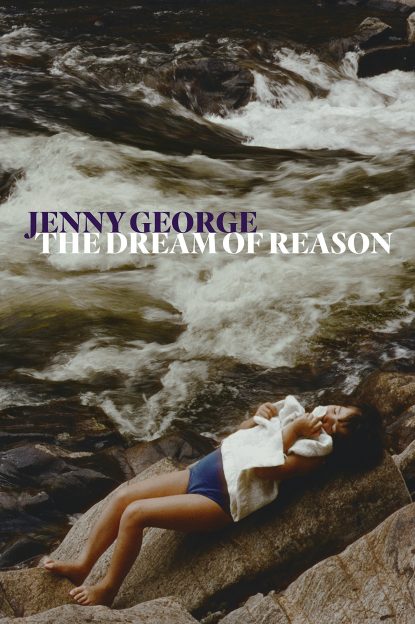

Cover of “The Dream of Reason” (Copper Canyon Press, Port Townsend, Washington, 2018; 65 pp., $16) by Jenny George

Last week we swung both legs over the fence from winter to spring. It’s just as muddy and cool on one side as the other, yet we know we’ve moved subtly from where we were to the ground of new life. A promise entered. Lent to Easter and life to death work much the same way.

I don’t know if poet Jenny George had any of this in mind while crafting the outstanding poems in her debut collection “The Dream of Reason” (Copper Canyon Press, Port Townsend, Washington, 2018; 65 pp., $16), but she pulls the reader from what seems mundane — such as a fascination with pigs — over to the lofty with poems on life and death through natural metaphors that resurface in many of its poems.

That theme of Lent to Easter, winter to spring, life to death appears explicitly in poem titles such as “Winter Variations,” “Spring” (two of the same title), “First Day of Lent,” “Easter” and “Everything is Restored.”

The latter follows a baby’s afternoon meal of pureed prunes, how he drifts off to sleep in his crib and how his mother knows harm will come to him and her in some form, inevitable as an ocean that keeps on breaking.

She is well aware of this gradual logic of drowning through the day and as evening fills the house she folds up the ocean and shuts it in a cupboard.

[hotblock]

This scene of mother-son bliss and lurking danger is followed by “Death of a Child,” a four-part poem that does not flinch on this hardest of subjects. It’s easy to see why, after describing This is how a child dies: | His breath curdles, his hands soften … the mother repeats herself saying, I can’t explain it. | I can’t explain it.

For her this is the afterlife in which she is not dead but remains in a field with the boy-shaped hole in her life, finding something close to an explanation in the unseen:

There’s something uneasy in the field.

A wake. A ripple in the cloth.

We see the green corn moving

But not the thing that moves it.

The atoms of our bodies turn

bright gold and silky. Aimed

at death, we live. We keep on

doing this. Night unfolds helplessly

into day. Beyond the field are more

fields and through them, too –

this current. What is it? Where

is it going? did you see it? Can you

catch it? Can you kill it? Can you hold

it still? Can you hold it still forever?

Death from another perspective comes from a series of 16 poems about pigs, those animals raised to be killed in order to keep people alive.

In one, a pig sleeps: The flickering candle | of a dream moves his warty eyelids. | All sleeping things are children.

In another, a swineherd gives his belt to a sow to bite on as she gives birth: She mouthed hard | and the calf came out like jelly, inert | and cooling on the trampled straw. … A few minutes later, she stood. | Drank a little water from the trough. | His belt where she chewed it | was like chewed bread. And how | did you imagine mercy would look?

The series’ final poem, “Westward Expansion,” completes the meditations on the life and death of pigs — Take a newborn calf and wind it | in a piece of cloth, it is no different | from any organ lifted out of a body — while also transitioning to the book’s final set of poems that intensifies the theme.

[tower]

“New World” opens with a vision of paradise perhaps for pigs but also for people. There are no slaughterhouses … | there are no feedlots for fattening …. It concludes, In the morning, the sun may rise. Who knows. There is nothing to be longed for.

“Sword-Swallower” picks up the theme of the soul: The soul enters the body | through the mouth.| So the legends say. | I say: the soul enters | through childhood. … Sleep: that ancient union | of death with its body. | The child sleeps. | As in – the child returns | to the time before her body.

George keeps the undercurrent of childhood, nature, dreams, life and death flowing beneath her poems. For example in “The Drowning,” children skate then lie dreaming on an iced-over lake knowing that a girl was pulled dead the previous summer from the same water below them.

The images and overarching theme come together fully in a series of seven poems of the book’s title, “The Dream of Reason,” charting a girl’s course through a rural landscape and, perhaps, her growth into adulthood accompanied always by creatures dead, dying or in peril.

The poems could well accompany the book’s cover art that depicts a young girl sleeping peacefully with her comfort blanket pressed to her face, stretched on warm rocks — while behind her the powerful current of a river churns furiously.

At its conclusion the book crystalizes its themes and strikes a note of hope in the resurrection after death, which is the central focus of the Christian season coming into view: “Easter.” In this poem and the rest, Jenny George employs the beautiful and the disturbing to draw readers in the mystery of life, its seasons and what follows.

They say it is the soul that rises, not the body.

But the body does rise –

Overhead, in the spring wind

trees are touching each other

with quiet gestures.

Winter: the buried forms.

Then the snow drawn under the trees, then the rings

of snow gone entirely, spring rains —

and the trees green and bending.

They have taken up

the rain and used it.

The air is fresh, smelling of wood.

What will be the first to emerge?

The brain, pushing its murderous bulb

through the mud? The heart? No —

the heart is last to rise.

The first to emerge is the image.

PREVIOUS: Intersection of faith, politics explored by theologian, retired pope

NEXT: Powerful pro-life message of ‘Unplanned’ not for faint of heart

Share this story