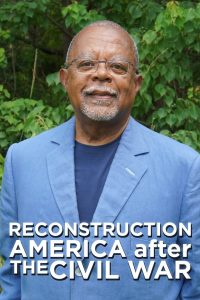

NEW YORK (CNS) — Arguably best known as the host of PBS’ popular genealogy series “Finding Your Roots,” prominent Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. takes on the same role for the network’s documentary “Reconstruction: America After the Civil War.”

NEW YORK (CNS) — Arguably best known as the host of PBS’ popular genealogy series “Finding Your Roots,” prominent Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. takes on the same role for the network’s documentary “Reconstruction: America After the Civil War.”

The important, challenging, if somewhat tendentious four-hour film — which Gates also executive produced — debuts with back-to-back episodes Tuesday, April 9, 9-11 p.m. EDT, and concludes Tuesday April 16 in the same time slot. Air times may vary in some markets, so viewers should check local listings.

The first two episodes focus on what most historians would consider the Reconstruction Era: the 12 years following the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865 during which federal Army troops protected the newly won rights of African Americans. The soldiers were withdrawn in the wake of the 1876 presidential election as part of a backroom deal to settle that disputed contest.

Subsequent installments, however, make the case that the title period should be understood more broadly as embracing the full 50 years after the end of the War Between the States. They thus carry the story forward into the 20th century and almost to the eve of U.S. involvement in the First World War.

[hotblock]

The horrific killing of nine African Americans at Charleston, South Carolina’s historic “Mother” Emmanuel AME Church in June 2015 by white male Dylann Roof epitomizes, in the filmmakers’ judgment, the distressing resurgence of white supremacy and racial violence in contemporary America.

If our society wants to understand “the roots of the tragedy at Mother Emmanuel” and others like it, Gates asserts, coming to terms with Reconstruction is “where we need to start.”

Gates and his “Finding Your Roots” collaborator Dyllan McGee rely heavily on a seemingly inexhaustible supply of commentators to enhance Gates’ narration. Computer animation illustrating dramatic incidents and actors’ recitation of the words of people critically important to the time — Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Ida B. Wells, for example — add to the commentary.

But it’s the many wonderfully evocative photographs that especially command viewers’ attention.

Much of the history the documentarians unpack in “Reconstruction” may come as a revelation to viewers. In the war’s immediate aftermath, African Americans were elected in large numbers to Congress and statehouses throughout the South. These leaders included the first black man to serve on Capitol Hill, Mississippi Sen. Hiram Revels, elected in 1870.

[tower]

Newly liberated African Americans consequently experienced for the first time what it was like to be “fully integrated into the highest echelon of political society,” says Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, a UCLA law professor who also teaches at Columbia Law School.

A backlash came in the form of lynching, convict-leasing programs that provided free labor to landowners, voter suppression efforts, Jim Crow laws and the erection of Confederate monuments.

By the turn of the 20th century, two African American leaders had emerged who offered starkly different visions for African American progress: Washington and W.E.B. Dubois.

Having become the first black man to obtain a doctorate from Harvard in 1895, Dubois promoted a “talented tenth” of intellectuals who could lift up others in the race. Washington, the founder of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, by contrast, emphasized self-improvement and economic independence for blacks more generally, seeking to “dignify and glorify common labor.”

Predictably, “Reconstruction” contains some difficult material, including candid depictions of slavery, lynching and other violence. Add in racist slurs and caricatures as well as fleeting nudity in a nonsexual context and it’s clear that the series is safest for grown-ups. Given the educational value of this historical retrospective, however, parents may feel mature teens will benefit from it.

Viewers’ reaction to the program will depend, at least in part, on their political outlook. “Reconstruction” powerfully indicts America’s legacy of injustice, but it does so with a somewhat heavy hand. That may limit appreciation for this admirable show to those who more or less concur with Gates’ worldview.

***

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Pope, youth minister suggest how to reach young Catholics

NEXT: Recipe: Sweet Easter pie with ancient farro

Share this story