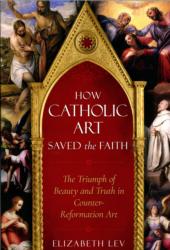

“How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art”

“How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art”

by Elizabeth Lev.

Sophia Institute Press (Manchester, New Hampshire, 2018).

310 pp. $18.95.

The best part of this book is the collection of glossy photos showing masterpieces of 16th- and 17th-century Italian art. The sculptures and paintings exemplify how artistic geniuses delved into Catholicism’s deposit of faith to convey biblical and theological themes and events.

The next best thing is the author’s description of the techniques used by artists to draw the viewer into their works and direct eyes to the sections giving visual expression to religious concepts.

The major drawback is that these photos and descriptions are surrounded by pietistic, apologetic short essays defending Catholic truths against the criticisms of the Protestant Reformation. At times, it’s as if the photos are illustrating a grade school Catholic tract rather then showing how great art can communicate profound and nuanced religious ideas.

[hotblock]

The book’s aim is to show how Catholic art “saved the faith” in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation that questioned important Catholic doctrines such as the number of sacraments, Christ’s real presence in the Eucharist and the intercession of Mary and the saints. While post-Reformation Catholic art and architecture certainly reaffirmed Catholicism, saying that it “saved the faith” is an exaggeration as if Catholicism would have disappeared if artists had not depicted its truths.

Also, almost all of the artists and architects in the book are Italian and their works were done in Italy, mostly for Italian ecclesiastics and Catholic nobles. While the Reformation gained important ground among kings and clergy in central and northern Europe, the Italian peninsula was safe. The papacy was based in Rome and popes also were temporal rulers of large swatches of central Italy. So the effect of these works on stemming the growth of Protestant influence is debatable.

The author, Elizabeth Lev, is a U.S.-born art historian living in Rome. Although she is adept at explaining how artists communicate, Lev also tends to exaggerate at times regarding the Reformation and its repercussions. She posits that Catholics chose to battle the Reformation with art rather than fighting as did the Protestants, only mentioning in passing that decades of wars between Catholic and Protestant states took place, costing millions of lives.

The artists and architecture discussed in this book cover the late Renaissance and Baroque periods dominated by such giants as Michelangelo, Caravaggio and Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Lev provides insightful descriptions of how sculptors, painters and architects masterfully conveyed their themes. She shows how artists gave a sensuousness to Mary Magdalene, often depicted as a repentant prostitute, by seductively showing her bare arms, shoulders and breasts as signs of the “before” part of her converted life. However, she downplays the idea that some artists may have used sensuality to symbolize spiritual joy and ecstasy.

Lev insightfully tells how Caravaggio uses light, finger pointing, eye contact and hand gestures to show the dynamism of the interaction between Christ and St. Matthew when Jesus calls the tax collector to become an apostle.

The book needs more of this: how art imitates Catholic truths.

***

Bono is a retired CNS staff writer.

PREVIOUS: ‘Spider-Man: Far From Home’ spins a snappy, substantial tale

NEXT: ‘Chasing the Moon’ offers surprises in Apollo 11’s story

Share this story