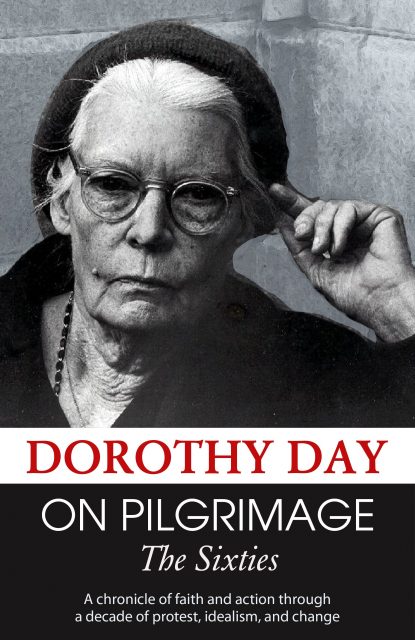

This is the book cover of “On Pilgrimage: The Sixties” by Dorothy Day, edited by Robert Ellsberg. The book is reviewed by Rachelle Linner. (CNS photo/courtesy Orbis Books)

“On Pilgrimage: The Sixties” by Dorothy Day, edited by Robert Ellsberg. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York, 2021). 316 pp., $28.

There are several ways one can read this wonderful book, a well-edited collection of Dorothy Day’s “On Pilgrimage” columns from the Catholic Worker from 1960 to 1969.

It can be read for the sheer pleasure of hearing the voice of Day, whose richly textured prose invites the reader into her unique experiences.

The columns are letters, not essays, and her lush attention to detail gives us vibrant images from her travels — to Cuba, to Rome, to the American South during the civil rights movement, to anti-war protests in New York and farmworker strikes in California, and to her daughter and grandchildren in Vermont.

Day’s writing, like her faith, is incarnational, and her word portraits are unfailingly engaging. She writes about people who are well known to the Catholic Worker community — A.J. Muste, Ignazio Silone, Danilo Dolci, Cesar Chavez, Peter Maurin, Ammon Hennacy.

The books and authors cited and admired show her wide-ranging intelligence and deep formation in history, theology and literature.

It can be read for a unique response to the social and political complexities of the 1960s. She offers a passionate denunciation of the war in Vietnam, conveys her principled and costly opposition to nuclear weapons, and shows the risks she took to support civil rights and migrant workers.

But above all, “On Pilgrimage” is a work of profound ascetical spirituality. One does not have to be Catholic to perform the corporal works of mercy or to risk imprisonment in opposition to systemic injustice and war.

[hotblock]

But Day’s embrace of voluntary poverty was the expression of a deep penitential spirit that itself rested on her love for, and desire to imitate, the poor Jesus of Nazareth: “The mystery of the poor is this: that they are Jesus, and what you do for them you do for him. It is the only way we have of knowing and believing in our love. The mystery of poverty is that by sharing in it, making ourselves poor in giving to others, we increase our knowledge of and belief in love.”

She is writing about her own spirituality when she eulogizes Hugh Madden, a man whose pilgrimages and penances are reminiscent of the stories of the desert fathers and mothers. “Why penance? For the napalm, the bombing in Vietnam perhaps. Because we are all guilty. God help us.”

She writes a stunning remembrance of Madeline Krider, a benefactor who was treated with contempt on a visit to the Catholic Worker, taken for a “poor, old and unattractive” woman.

Yet she took this, quoting St. Francis, as “perfect joy … bringing her a bit nearer to the suffering of Christ and by her very sharing, lightening to some degree the burden of others.”

In 1965, Day joined an international group of women who undertook a 10-day fast for peace during the final session of the Second Vatican Council.

“I had offered my fast in part for the victims of famine all over the world, and it seemed to me that I had very special pains. They were certainly of a kind I have never had before, and they seemed to pierce to the very marrow of my bones when I lay down at night. … I could only feel that I had been given some little information of the hunger of the world. God help us, living as we do, in the richest country in the world and so far from approaching the voluntary poverty we esteem and reach toward.”

[hotblock2]

This is not the type of spiritual writing we are accustomed to reading, a spirituality that is often, unfortunately, yoked to an unhealthy theological anthropology that diminishes physical and psychological integrity.

Yet it would be foolish to dismiss it simply as an artifact of the pre-Vatican II spirituality in which Day was formed. If it is so bankrupt, how could it have sustained her through her arduous 50-year pilgrimage, from the founding of the Catholic Worker Movement in 1933 to her death in 1980?

“On Pilgrimage” shows us the creative synthesis Day forged between American radicalism and traditional Catholic spirituality. She offers a prophetic template of what it would look like to take seriously the demands of faith and public life.

“There is plenty to do, for each one of us, working on our own hearts, changing our own attitudes, in our own neighborhoods. If the just man falls seven times daily, we each one of us fall more than that in thought, word, and deed. Prayer and fasting, taking up our own cross daily and following him, doing penance, these are the hard words of the Gospel.”

These are the hard words of Dorothy Day, seen in this beautiful book that lets us see the luminous, difficult, suffering and loving life in which she forged a new vision of holiness.

***

Linner, a spiritual director, freelance writer and reviewer, has a master’s degree in theology from Weston Jesuit School of Theology.

PREVIOUS: ‘The Many Saints of Newark’ prequel probes mobster’s roots

NEXT: In ‘Mass,’ a school shooting’s aftermath opens wounds, and healing

Share this story